by Emrys Westacott

America is a truck rolling down a hill towards a cliff. The downhill slope is the erosion of democratic norms; the cliff is the point where anti-democratic forces become powerful enough to crush democratic opposition by authoritarian means. The re-election of Donald Trump would very likely see the country sail over that cliff.

America is a truck rolling down a hill towards a cliff. The downhill slope is the erosion of democratic norms; the cliff is the point where anti-democratic forces become powerful enough to crush democratic opposition by authoritarian means. The re-election of Donald Trump would very likely see the country sail over that cliff.

In this situation, anyone who believes that it would be a good thing to preserve what remains of American democracy and, if possible, to strengthen it and extend it so as to better realize the nation’s professed ideals, should want to see Trump and his Republican enablers in Congress soundly defeated. So anyone who has a vote should use it accordingly. Each such vote is a hand on the wheel trying to steer the truck away from disaster. To vote for Trump is to help push the truck over the cliff. To refuse to vote for Joe Biden (the presumptive Democratic candidate), especially in swing states, is effectively to stand by and watch as disaster threatens.

I understand the frustration progressive-minded people feel with a candidate like Biden. I feel it too. Once again, as so many times before, we are asked to vote for an establishment politician whose record does not indicate any deep commitment to really challenging the status quo, because the alternative is so much worse. There are only two arguments to support withholding one’s vote; but both of them are bad. Read more »

Actress Cameron Diaz and her business partner, the entrepreneur Katherine Power, have been all over various media promoting

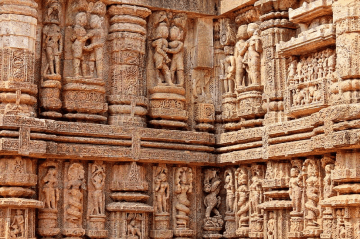

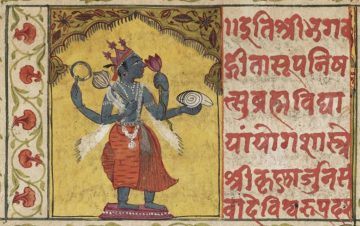

Actress Cameron Diaz and her business partner, the entrepreneur Katherine Power, have been all over various media promoting  To include the Upanishads and the Bhagavad Gita in a series called “Footnotes to Plato” may seem odd for many reasons – some obvious, some less so. But to address the oddity is invigorating, and offers a way of considering the necessity of placing these works in the wider discussion, as well as the historical and conceptual impediments to doing so.

To include the Upanishads and the Bhagavad Gita in a series called “Footnotes to Plato” may seem odd for many reasons – some obvious, some less so. But to address the oddity is invigorating, and offers a way of considering the necessity of placing these works in the wider discussion, as well as the historical and conceptual impediments to doing so. It has been just over five months since the first case of COVID-19 was detected in India. With nearly a million confirmed cases, the country now has the third greatest number of infections, behind only the United States and Brazil. At least 25,000 people have died.

It has been just over five months since the first case of COVID-19 was detected in India. With nearly a million confirmed cases, the country now has the third greatest number of infections, behind only the United States and Brazil. At least 25,000 people have died. This is not the usual bland political memoir offering yet another story of finding the American dream. In part, this is because Ilhan Omar is not another dull politician. That much is obvious from the waves she has made in Washington, DC since becoming a member of Congress in 2019. Omar, from Minnesota, and Rashida Tlaib, from Michigan, are the first two Muslim women elected to Congress. Along with two other women of colour, who are also in their first term, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Ayanna Pressley, they are known as “the squad”. The 181-year-old ban on wearing religious head-wear in the House chamber was changed in 2019, allowing Omar to wear her hijab on the floor of Congress. While running for Congress, Omar admits, she was worried that this rule would keep her from being able to serve.

This is not the usual bland political memoir offering yet another story of finding the American dream. In part, this is because Ilhan Omar is not another dull politician. That much is obvious from the waves she has made in Washington, DC since becoming a member of Congress in 2019. Omar, from Minnesota, and Rashida Tlaib, from Michigan, are the first two Muslim women elected to Congress. Along with two other women of colour, who are also in their first term, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Ayanna Pressley, they are known as “the squad”. The 181-year-old ban on wearing religious head-wear in the House chamber was changed in 2019, allowing Omar to wear her hijab on the floor of Congress. While running for Congress, Omar admits, she was worried that this rule would keep her from being able to serve.