Ed Yong in The Atlantic:

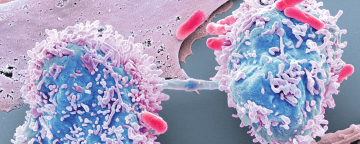

Seven years ago, the White House was bracing itself for not one pandemic, but two. In the spring of 2013, several people in China fell sick with a new and lethal strain of H7N9 bird flu, while an outbreak of MERS—a disease caused by a coronavirus—had spread from Saudi Arabia to several other countries. “We were dealing with the potential for both of those things to become a pandemic,” says Beth Cameron, who was on the National Security Council at the time.

Seven years ago, the White House was bracing itself for not one pandemic, but two. In the spring of 2013, several people in China fell sick with a new and lethal strain of H7N9 bird flu, while an outbreak of MERS—a disease caused by a coronavirus—had spread from Saudi Arabia to several other countries. “We were dealing with the potential for both of those things to become a pandemic,” says Beth Cameron, who was on the National Security Council at the time.

Neither did, thankfully, but we shouldn’t mistake historical luck for future security. Viruses aren’t sporting. They will not refrain from kicking you just because another virus has already knocked you to the floor. And pandemics are capricious. Despite a lot of research, “we haven’t found a way to predict when a new one will arrive,” says Nídia Trovão, a virologist at the National Institutes of Health. As new diseases emerge at a quickening pace, the only certainty is that pandemics are inevitable. So it is only a matter of time before two emerge at once.

“We have to prepare for a pandemic to happen at any time, and ‘any time’ can be when we’re already dealing with one pandemic,” Cameron told me.

More here.

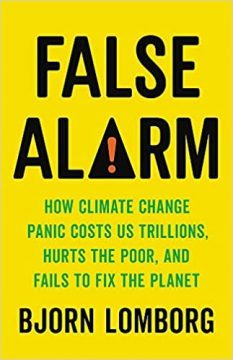

The thesis of Bjorn Lomborg’s “False Alarm” is simple and simplistic: Activists have been sounding a false alarm about the dangers of climate change. If we listen to them, Lomborg says, we will waste trillions of dollars, achieve little and the poor will suffer the most. Science has provided a way to carefully balance costs and benefits, if we would only listen to its clarion call. And, of course, the villain in this “false alarm,” the boogeyman for all of society’s ills, is the hyperventilating media. Lomborg doesn’t use the term “fake news,” but it’s there if you read between the lines.

The thesis of Bjorn Lomborg’s “False Alarm” is simple and simplistic: Activists have been sounding a false alarm about the dangers of climate change. If we listen to them, Lomborg says, we will waste trillions of dollars, achieve little and the poor will suffer the most. Science has provided a way to carefully balance costs and benefits, if we would only listen to its clarion call. And, of course, the villain in this “false alarm,” the boogeyman for all of society’s ills, is the hyperventilating media. Lomborg doesn’t use the term “fake news,” but it’s there if you read between the lines. T

T This isn’t a style of the Church, Italy, a patron, or a doctrine. It’s a personal style, the work of a self-taught 40-something gay man who devised ways to dye one’s hair blond as well as build bridges. Art history has been going through regular stylistic shifts ever since. This is what a social revolution looks like.

This isn’t a style of the Church, Italy, a patron, or a doctrine. It’s a personal style, the work of a self-taught 40-something gay man who devised ways to dye one’s hair blond as well as build bridges. Art history has been going through regular stylistic shifts ever since. This is what a social revolution looks like. In the summer of 1977, on a field trip in northern Patagonia, the American archaeologist Tom Dillehay made a stunning discovery. Digging by a creek in a nondescript scrubland called Monte Verde, in southern Chile, he came upon the remains of an ancient camp. A full excavation uncovered the trace wooden foundations of no fewer than 12 huts, plus one larger structure designed for tool manufacture and perhaps as an infirmary. In the large hut, Dillehay found gnawed bones, spear points, grinding tools and, hauntingly, a human footprint in the sand. The ancestral Patagonians—inhabitants of Tierra del Fuego and the Magellan Straits—had erected their domestic quarters using branches from the beech trees of a long-gone temperate forest, then covered them with the hides of vanished ice age species, including mastodons, saber-toothed cats, and giant sloths.

In the summer of 1977, on a field trip in northern Patagonia, the American archaeologist Tom Dillehay made a stunning discovery. Digging by a creek in a nondescript scrubland called Monte Verde, in southern Chile, he came upon the remains of an ancient camp. A full excavation uncovered the trace wooden foundations of no fewer than 12 huts, plus one larger structure designed for tool manufacture and perhaps as an infirmary. In the large hut, Dillehay found gnawed bones, spear points, grinding tools and, hauntingly, a human footprint in the sand. The ancestral Patagonians—inhabitants of Tierra del Fuego and the Magellan Straits—had erected their domestic quarters using branches from the beech trees of a long-gone temperate forest, then covered them with the hides of vanished ice age species, including mastodons, saber-toothed cats, and giant sloths. A breathalyzer designed to detect multiple cancers early is being tested in the UK. Several illnesses

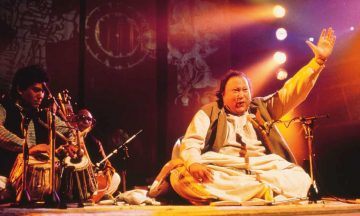

A breathalyzer designed to detect multiple cancers early is being tested in the UK. Several illnesses Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan

Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan In 1931, the Austrian logician Kurt Gödel pulled off arguably one of the most stunning intellectual achievements in history.

In 1931, the Austrian logician Kurt Gödel pulled off arguably one of the most stunning intellectual achievements in history. There are two boxes on a table, one red and one green. One contains a treasure. The red box is labelled “exactly one of the labels is true”. The green box is labelled “the treasure is in this box.”

There are two boxes on a table, one red and one green. One contains a treasure. The red box is labelled “exactly one of the labels is true”. The green box is labelled “the treasure is in this box.” WHAT IS A WOMAN’S MARGINAL UTILITY?

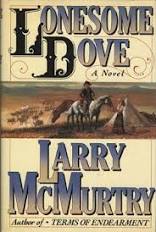

WHAT IS A WOMAN’S MARGINAL UTILITY? By the halfway point in my journey through Lonesome Dove two things started happening. As I began communicating my Keats-on-Chapman’s-Homer “discovery” to friends, it became clear that the book inspired something more akin to faith than admiration or love. People hadn’t just read the book; they had converted or pledged allegiance to it. When a friend came to dinner and saw my copy on the table she explained that she had been given the middle name MacRae, in honour of Gus. I fell prey to a kind of fanaticism myself, emailing an unsuspecting Zadie Smith to ask why anyone would bother with even a page of Saul Bellow when they could be immersed in Lonesome Dove. When she wrote back that she couldn’t bear Bellow or westerns I was tempted to respond, insanely, that it wasn’t a western. And yet – to deploy a favourite hesitation of Steiner’s – perhaps an underlying sanity or logic was at work.

By the halfway point in my journey through Lonesome Dove two things started happening. As I began communicating my Keats-on-Chapman’s-Homer “discovery” to friends, it became clear that the book inspired something more akin to faith than admiration or love. People hadn’t just read the book; they had converted or pledged allegiance to it. When a friend came to dinner and saw my copy on the table she explained that she had been given the middle name MacRae, in honour of Gus. I fell prey to a kind of fanaticism myself, emailing an unsuspecting Zadie Smith to ask why anyone would bother with even a page of Saul Bellow when they could be immersed in Lonesome Dove. When she wrote back that she couldn’t bear Bellow or westerns I was tempted to respond, insanely, that it wasn’t a western. And yet – to deploy a favourite hesitation of Steiner’s – perhaps an underlying sanity or logic was at work. In the 1966 movie Fantastic Voyage, a team of scientists is shrunk to fit into a tiny submarine so that they can navigate their colleague’s vasculature and rid him of a deadly blood clot in his brain. This classic film is one of many such imaginative biological journeys that have made it to the big screen over the past several decades. At the same time, scientists have been working to make a similar vision a reality: tiny robots roaming the human body to detect and treat disease.

In the 1966 movie Fantastic Voyage, a team of scientists is shrunk to fit into a tiny submarine so that they can navigate their colleague’s vasculature and rid him of a deadly blood clot in his brain. This classic film is one of many such imaginative biological journeys that have made it to the big screen over the past several decades. At the same time, scientists have been working to make a similar vision a reality: tiny robots roaming the human body to detect and treat disease.

I don’t believe in coincidences, at least not big ones. That’s why the sea change the sister arts of poetry, painting, and music underwent at the turn of the 20th century has always intrigued me. All of them veered off course at virtually the same time and in virtually the same way. To paraphrase Yul Brynner in The King and I, “It was a puzzlement.” It was as if a group of high achieving artists had met, mafia-style, in some non-disclosed location to plan mischief against the art world. It had all the hallmarks of a conspiracy. They would do something so radical, so scandalous that it would turn the art world on its head.

I don’t believe in coincidences, at least not big ones. That’s why the sea change the sister arts of poetry, painting, and music underwent at the turn of the 20th century has always intrigued me. All of them veered off course at virtually the same time and in virtually the same way. To paraphrase Yul Brynner in The King and I, “It was a puzzlement.” It was as if a group of high achieving artists had met, mafia-style, in some non-disclosed location to plan mischief against the art world. It had all the hallmarks of a conspiracy. They would do something so radical, so scandalous that it would turn the art world on its head.