Kamila Shamsie in Tate Etc:

It is worth mentioning here that it’s widely believed that the greatest piece of writing – indeed, the greatest piece of art – created about Partition is a short story, called ‘Toba Tek Singh’, just a handful of pages long, by the Urdu writer Saadat Hasan Manto. The story is about the (and I’m using the language of the time) inmates of a lunatic asylum in the district of Toba Tek Singh, near Lahore. When Partition takes place, the lunatics must be divided between India and Pakistan. It ends with one of the inmates lying down in no man’s land, muttering nonsense words: ‘Upar di gur gur di annexe di be-dhiyana mung di daal of di Toba Tek Singh and Pakistan’. A rough translation would go: ‘Upstairs the rumbling the annex the heedlessness the lentils of Toba Tek Singh and Pakistan’. A man speaking nonsense words in a world where reality is beyond what words can convey – that is part of the effectiveness of this story. The Partition of word and meaning. The inability of language to make sense of what is going on, except through conveying senselessness.

It is certainly true that sometimes the linearity of language, the logic of first this-then this-then this, words become sentences become paragraphs – sometimes that seems too neat, too false, to convey a shattering, a sundering.

I’ve felt this in my own writing. Some years ago, when writing about the dropping of the atom bomb on Nagasaki, I knew the moment of the bomb detonating could only be depicted by two blank pages – the closest thing to a flash of white light I could put on a page.

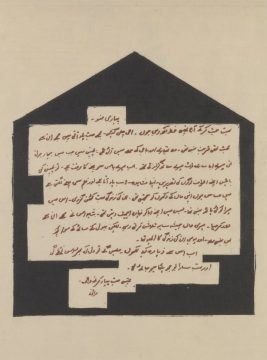

If I had to invent a story about my life as a writer leading up to the moment of those two blank pages, it would start with me looking and looking at that framed letter on the wall and choosing not to read it. That was the moment when I first knew that sometimes words are not what you need to convey the weight of a particular kind of moment.

As a writer it’s hard not to be drawn to considerations of how text functions in art – I’m particularly interested in how it functions around events that seem to leach the meaning out of everyday language, or else make every word so freighted that it collapses under its own weight. What are words when you don’t use them to convey their literal meaning, but find a way to burrow down into them and find the symbolic heft of them instead?

More here.

When I was a child, my brother and I played a computer game based on the Indiana Jones movie franchise. In the course of his adventures, Indy would sometimes come to a delicate impasse that required tact and nuance to resolve. Some adversary was blocking his path to a relic or treasure (including, oddly enough, one of Plato’s lost dialogues), and he needed to say just the right thing to get past them and on to the next challenge. The game offered players a selection of five or so sentences to choose from. The world would sit there in 8-bit paralysis and wait while we pondered how to make it do what we wanted. Press enter on the right sentence and pixelated Indy would sail through. Choose something inapt and game over.

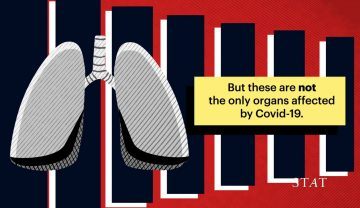

When I was a child, my brother and I played a computer game based on the Indiana Jones movie franchise. In the course of his adventures, Indy would sometimes come to a delicate impasse that required tact and nuance to resolve. Some adversary was blocking his path to a relic or treasure (including, oddly enough, one of Plato’s lost dialogues), and he needed to say just the right thing to get past them and on to the next challenge. The game offered players a selection of five or so sentences to choose from. The world would sit there in 8-bit paralysis and wait while we pondered how to make it do what we wanted. Press enter on the right sentence and pixelated Indy would sail through. Choose something inapt and game over. What they are understanding is that this coronavirus “has such a diversity of effects on so many different organs, it keeps us up at night,” said Thomas McGinn, deputy physician in chief at Northwell Health and director of the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research. “It’s amazing how many different ways it affects the body.”

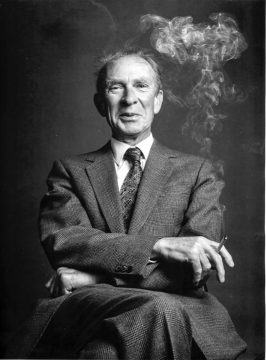

What they are understanding is that this coronavirus “has such a diversity of effects on so many different organs, it keeps us up at night,” said Thomas McGinn, deputy physician in chief at Northwell Health and director of the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research. “It’s amazing how many different ways it affects the body.” When I migrated from Cambridge to my new post at Pembroke College Oxford in the fall of 1969 I got the sense that many of the Old Guard there regarded me as some kind of foreign usurper. Perhaps their own favourite pupils had not been offered the job as they undoubtedly deserved. An exception was Peter Strawson, who was always friendly, and whom I came to admire greatly. Some years later when I belonged to a rather grubby photography workshop in the city I persuaded him to come downtown for me to make a portrait of him. I hope that some of the affection I felt comes through, as well as his undoubted amusement at the occasion.

When I migrated from Cambridge to my new post at Pembroke College Oxford in the fall of 1969 I got the sense that many of the Old Guard there regarded me as some kind of foreign usurper. Perhaps their own favourite pupils had not been offered the job as they undoubtedly deserved. An exception was Peter Strawson, who was always friendly, and whom I came to admire greatly. Some years later when I belonged to a rather grubby photography workshop in the city I persuaded him to come downtown for me to make a portrait of him. I hope that some of the affection I felt comes through, as well as his undoubted amusement at the occasion. In 1977, the poet Adrienne Rich exhorted a graduating class of young women to think of education

In 1977, the poet Adrienne Rich exhorted a graduating class of young women to think of education  Arising by most accounts in the last decades of the nineteenth century, the novel of ideas reflects the challenge posed by the integration of externally developed concepts long before the arrival of conceptual art. Although the novel’s verbal medium would seem to make it intrinsically suited to the endeavor, the mission of presenting “ideas” seems to have pushed a genre famous for its versatility toward a surprisingly limited repertoire of techniques. These came to obtrude against a set of generic expectations—nondidactic representation; a dynamic, temporally complex relation between events and the representation of events; character development; verisimilitude—established only in wake of the novel’s separation from history and romance at the start of the nineteenth century. Compared to these and even older, ancient genres like drama and lyric, the novel is astonishingly young, which is perhaps why departures from its still only freshly consolidated conventions seem especially noticeable.

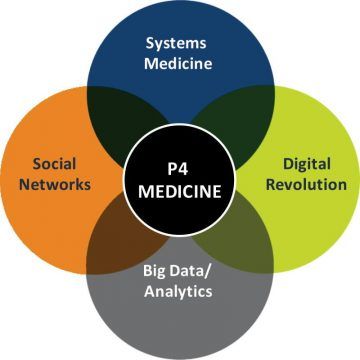

Arising by most accounts in the last decades of the nineteenth century, the novel of ideas reflects the challenge posed by the integration of externally developed concepts long before the arrival of conceptual art. Although the novel’s verbal medium would seem to make it intrinsically suited to the endeavor, the mission of presenting “ideas” seems to have pushed a genre famous for its versatility toward a surprisingly limited repertoire of techniques. These came to obtrude against a set of generic expectations—nondidactic representation; a dynamic, temporally complex relation between events and the representation of events; character development; verisimilitude—established only in wake of the novel’s separation from history and romance at the start of the nineteenth century. Compared to these and even older, ancient genres like drama and lyric, the novel is astonishingly young, which is perhaps why departures from its still only freshly consolidated conventions seem especially noticeable. The highlights of Leroy Hood’s scientific career are like peaks in a mountain range spanning diverse fields, from molecular immunology and engineering, to genomics, to systems medicine. But Hood doesn’t think his trailblazing approach should be unusual, emphasizing that “one of the really key things about science is every 10 or 15 years, you really make a dramatic break and do something new… and you have to learn a lot before you can make fundamental contributions.”

The highlights of Leroy Hood’s scientific career are like peaks in a mountain range spanning diverse fields, from molecular immunology and engineering, to genomics, to systems medicine. But Hood doesn’t think his trailblazing approach should be unusual, emphasizing that “one of the really key things about science is every 10 or 15 years, you really make a dramatic break and do something new… and you have to learn a lot before you can make fundamental contributions.” The term “

The term “ We know from every disaster movie that time is supposed to accelerate, not stand still, during a catastrophe. If asked to draw a scenario months ago, most of us would have imagined moments of chaos and disorder, akin to the profound social chaos in Florence during the plague as described by Boccaccio in his 14th-century work The Decameron, “all respect for the laws of God and man … broken down.”

We know from every disaster movie that time is supposed to accelerate, not stand still, during a catastrophe. If asked to draw a scenario months ago, most of us would have imagined moments of chaos and disorder, akin to the profound social chaos in Florence during the plague as described by Boccaccio in his 14th-century work The Decameron, “all respect for the laws of God and man … broken down.” Sudden, radical transformations of substances known to humanity for eons, like water freezing and soup steaming over a fire, remained mysterious until well into the 20th century. Scientists observed that substances typically change gradually: Heat a collection of atoms a little, and it expands a little. But nudge a material past a critical point, and it becomes something else entirely.

Sudden, radical transformations of substances known to humanity for eons, like water freezing and soup steaming over a fire, remained mysterious until well into the 20th century. Scientists observed that substances typically change gradually: Heat a collection of atoms a little, and it expands a little. But nudge a material past a critical point, and it becomes something else entirely. Scientism – the belief that science is the only valid source of knowledge and that all legitimate questions can be answered by science – is what spawns pseudoscience and science denialism. If science is treated as though it not only informs us but also dictates how our lives ought to be lived and how society ought to be run, then it is easier to peddle in the baseless denial of scientific claims than it is to challenge the illegitimate claim of authority over our choices made on science’s behalf.

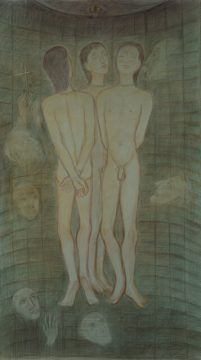

Scientism – the belief that science is the only valid source of knowledge and that all legitimate questions can be answered by science – is what spawns pseudoscience and science denialism. If science is treated as though it not only informs us but also dictates how our lives ought to be lived and how society ought to be run, then it is easier to peddle in the baseless denial of scientific claims than it is to challenge the illegitimate claim of authority over our choices made on science’s behalf. This is not to say that Klossowski was standoffish. One of the interesting things about him is that once you finally notice him you begin to see his shadowy presence everywhere in twentieth-century French culture. He was, for instance, an early French translator of Walter Benjamin—as well as Wittgenstein, Heidegger, and Kafka, among others. When very young, he was a secretary for André Gide and appears semidisguised as a character in Gide’s novel The Counterfeiters, a novel he appears to have helped edit and for which he also made illustrations (which were turned down for being too overtly erotic). The older brother of the painter Balthasar Klossowski de Rola, better known as Balthus, Klossowski was an artist himself, and his work is at once naïve and pornographically explicit in a way that sometimes references occult texts, mythology, and Klossowski’s own prose. He was a friend of Georges Bataille—and indeed Bataille’s own investigation of erotism might best be read in counterpoint to Klossowski. He was involved marginally with surrealists, spent time in a Dominican seminary, was later involved with the existentialists, and wrote philosophical texts on Friedrich Nietzsche and the Marquis de Sade that were influential for post-structuralism. His book-length economico-philosophical essay La Monnaie vivante (Living Currency) Foucault called “the best book of our times.” Fiction writer, philosopher, translator, and visual artist, Klossowski worked in many modes and media and seemed to touch the lives of many of the literary and artistic figures we now admire. Indeed, once he’s noticed, it’s hard not to suspect he’s lurking even where you don’t see him.

This is not to say that Klossowski was standoffish. One of the interesting things about him is that once you finally notice him you begin to see his shadowy presence everywhere in twentieth-century French culture. He was, for instance, an early French translator of Walter Benjamin—as well as Wittgenstein, Heidegger, and Kafka, among others. When very young, he was a secretary for André Gide and appears semidisguised as a character in Gide’s novel The Counterfeiters, a novel he appears to have helped edit and for which he also made illustrations (which were turned down for being too overtly erotic). The older brother of the painter Balthasar Klossowski de Rola, better known as Balthus, Klossowski was an artist himself, and his work is at once naïve and pornographically explicit in a way that sometimes references occult texts, mythology, and Klossowski’s own prose. He was a friend of Georges Bataille—and indeed Bataille’s own investigation of erotism might best be read in counterpoint to Klossowski. He was involved marginally with surrealists, spent time in a Dominican seminary, was later involved with the existentialists, and wrote philosophical texts on Friedrich Nietzsche and the Marquis de Sade that were influential for post-structuralism. His book-length economico-philosophical essay La Monnaie vivante (Living Currency) Foucault called “the best book of our times.” Fiction writer, philosopher, translator, and visual artist, Klossowski worked in many modes and media and seemed to touch the lives of many of the literary and artistic figures we now admire. Indeed, once he’s noticed, it’s hard not to suspect he’s lurking even where you don’t see him. For much of their history, intelligence tests have been rotten with the cultural and class biases of their makers, a diagnostic deck stacked against minorities, immigrants, and those at the bottom of the wage pyramid. Test designers have equated English-language fluency with intelligence, presumed a familiarity with upper-class pastimes such as tennis, and expected the examinee to provide the word “shrewd” as a synonym for “Jewish.” As late as the 1960 revision, the Stanford-Binet was presenting six-year-old children with crude cartoons of two women, one obviously Anglo-Saxon, the other a golliwog caricature of an African-American, with a broad nose and thick lips. The test accepted only one correct answer to the question, “Which is prettier?”12

For much of their history, intelligence tests have been rotten with the cultural and class biases of their makers, a diagnostic deck stacked against minorities, immigrants, and those at the bottom of the wage pyramid. Test designers have equated English-language fluency with intelligence, presumed a familiarity with upper-class pastimes such as tennis, and expected the examinee to provide the word “shrewd” as a synonym for “Jewish.” As late as the 1960 revision, the Stanford-Binet was presenting six-year-old children with crude cartoons of two women, one obviously Anglo-Saxon, the other a golliwog caricature of an African-American, with a broad nose and thick lips. The test accepted only one correct answer to the question, “Which is prettier?”12 A FEW LONG WEEKS AGO,

A FEW LONG WEEKS AGO,