Ed Yong in The Atlantic:

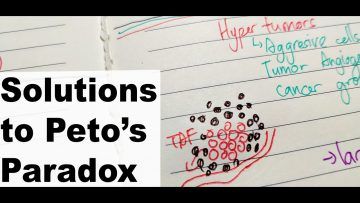

In 2012, on a whim, Vincent Lynch decided to search the genome of the African elephant to see if it had extra anti-cancer genes. Cancers happen when cells build up mutations in their DNA that allow them to grow and divide uncontrollably. Bigger animals, whose bodies comprise more cells, should therefore have a higher risk of cancer. This is true within species: On average, taller humans are more likely to develop tumors than shorter ones, and bigger dogs have a higher cancer risk than smaller ones.

In 2012, on a whim, Vincent Lynch decided to search the genome of the African elephant to see if it had extra anti-cancer genes. Cancers happen when cells build up mutations in their DNA that allow them to grow and divide uncontrollably. Bigger animals, whose bodies comprise more cells, should therefore have a higher risk of cancer. This is true within species: On average, taller humans are more likely to develop tumors than shorter ones, and bigger dogs have a higher cancer risk than smaller ones.

But this trend breaks down when you look across species. Elephants are no more susceptible to tumors than Chihuahuas, and whales are no more likely to develop cancers than humans—if anything, their risk is lower. That’s especially strange because big animals also tend to have longer life spans, giving more opportunities for each of their already abundant cells to become cancerous. They ought to be walking (or swimming) masses of tumors—but clearly they aren’t. For the vast majority of mammals that have been studied, the odds of dying from cancer range from 1 to 10 percent, whether you’re talking about a 50-gram grass mouse or a 5,000-kilogram African elephant.

This puzzling trend is called Peto’s paradox, named after the British epidemiologist Richard Peto, who described it in the 1970s. Since then, biologists have proposed hundreds of hypotheses to explain it. Some note that larger animals have lower metabolic rates; this reduces the rate at which they acquire mutations. Others have suggested that in big animals, tumors need more time to reach a lethal size; during that time, the tumors likely to grow debilitating secondary tumors of their own.

More here.

Most people who catch the new coronavirus don’t experience severe symptoms, and some have no symptoms at all. COVID-19 saves its worst for relatively few.

Most people who catch the new coronavirus don’t experience severe symptoms, and some have no symptoms at all. COVID-19 saves its worst for relatively few. NC: The first thing that comes to mind is the absolutely unprecedented scope and scale of participation, engagement, and public support. If you look at polls, it’s astonishing. The

NC: The first thing that comes to mind is the absolutely unprecedented scope and scale of participation, engagement, and public support. If you look at polls, it’s astonishing. The  The cost of

The cost of  I’m recovering from flu, so I’ve spent more time than usual by myself lately, with odd ideas swirling around in my feverish brain. Recently a bunch of different thoughts–about

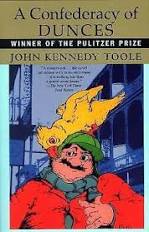

I’m recovering from flu, so I’ve spent more time than usual by myself lately, with odd ideas swirling around in my feverish brain. Recently a bunch of different thoughts–about  The New York publishers were wrong. A Confederacy of Dunces did, in fact, make a point, a fundamental one. Percy grasped it immediately: the book was a screed against American materialism and optimism, a defense of the oddball outcasts who live on the fringes and resist the push of progress, and a celebration of those who try to drop out with dignity.

The New York publishers were wrong. A Confederacy of Dunces did, in fact, make a point, a fundamental one. Percy grasped it immediately: the book was a screed against American materialism and optimism, a defense of the oddball outcasts who live on the fringes and resist the push of progress, and a celebration of those who try to drop out with dignity. While he was writing Edwin Drood, Dickens was imbibing large quantities of opium, a drug that allows us, Thomas De Quincey explained in Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, access to a ‘second life’. Opium also allows the ‘guilty man’, De Quincey continued, to regain ‘for one night … the hopes of his youth, and hands washed pure of blood’. But at the same time as releasing the guilty man from his chains, taking opium causes further feelings of guilt. ‘In the one crime of OPIUM’, wailed Coleridge, whose life was destroyed by it, ‘what crime have I not made myself guilty of!’

While he was writing Edwin Drood, Dickens was imbibing large quantities of opium, a drug that allows us, Thomas De Quincey explained in Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, access to a ‘second life’. Opium also allows the ‘guilty man’, De Quincey continued, to regain ‘for one night … the hopes of his youth, and hands washed pure of blood’. But at the same time as releasing the guilty man from his chains, taking opium causes further feelings of guilt. ‘In the one crime of OPIUM’, wailed Coleridge, whose life was destroyed by it, ‘what crime have I not made myself guilty of!’ Leviton:

Leviton: The best chess and Go players in the world aren’t human beings any more; they’re artificially-intelligent computer programs. But the best poker players are still humans. Poker is a laboratory for understanding how rationality works in real-world situations: it features stochastic events, incomplete information, Bayesian updating, game theory, reading other people, a battle between emotions and reason, and real-world stakes. Maria Konnikova started in psychology, turned to writing, and then took up professional-level poker, and has learned a lot along the way about the challenges of being rational. We talk about what games like poker can teach us about thinking and human psychology.

The best chess and Go players in the world aren’t human beings any more; they’re artificially-intelligent computer programs. But the best poker players are still humans. Poker is a laboratory for understanding how rationality works in real-world situations: it features stochastic events, incomplete information, Bayesian updating, game theory, reading other people, a battle between emotions and reason, and real-world stakes. Maria Konnikova started in psychology, turned to writing, and then took up professional-level poker, and has learned a lot along the way about the challenges of being rational. We talk about what games like poker can teach us about thinking and human psychology. There are distinct and deep-rooted traditions of rational empiricism and religious sermonizing in American history. But these two modes seem to have become fused together in a new form of argumentation that is validated by elite institutions like the universities, The New York Times, Gracie Mansion, and especially on the new technology platforms where battles over the discourse are now waged. The new mode is argument by commandment: It borrows the form to game the discourse of rational argumentation in order to issue moral commandments. No official doctrine yet exists for this syncretic belief system but its features have been on display in all of the major debates over political morality of the past decade. Marrying the technical nomenclature of rational proof to the soaring eschatology of the sermon, it releases adherents from the normal bounds of reason. The arguer-commander is animated by a vision of secular hell—unremitting racial oppression that never improves despite myths about progress; society as a ceaseless subjection to rape and sexual assault; Trump himself, arriving to inaugurate a Luciferean reign of torture. Those in possession of this vision do not offer the possibility of redemption or transcendence, they come to deliver justice. In possession of justice, the arguer-commander is free at any moment to throw off the cloak of reason and proclaim you a bigot—racist, sexist, transphobe—who must be fired from your job and socially shunned.

There are distinct and deep-rooted traditions of rational empiricism and religious sermonizing in American history. But these two modes seem to have become fused together in a new form of argumentation that is validated by elite institutions like the universities, The New York Times, Gracie Mansion, and especially on the new technology platforms where battles over the discourse are now waged. The new mode is argument by commandment: It borrows the form to game the discourse of rational argumentation in order to issue moral commandments. No official doctrine yet exists for this syncretic belief system but its features have been on display in all of the major debates over political morality of the past decade. Marrying the technical nomenclature of rational proof to the soaring eschatology of the sermon, it releases adherents from the normal bounds of reason. The arguer-commander is animated by a vision of secular hell—unremitting racial oppression that never improves despite myths about progress; society as a ceaseless subjection to rape and sexual assault; Trump himself, arriving to inaugurate a Luciferean reign of torture. Those in possession of this vision do not offer the possibility of redemption or transcendence, they come to deliver justice. In possession of justice, the arguer-commander is free at any moment to throw off the cloak of reason and proclaim you a bigot—racist, sexist, transphobe—who must be fired from your job and socially shunned. The pathologist makes do with red wine until an effective drug is available, the biochemist discards the bread from her sandwiches, and the mathematician indulges in designer chocolate with a clear conscience. The demographer sticks to vitamin supplements, and while the evolutionary biologist calculates the compensations of celibacy, the population biologist transplants gonads, but so far only those of his laboratory mice. Their common cause is to control and extend the healthy lifespan of humans. They want to cure ageing and the diseases that come with it.

The pathologist makes do with red wine until an effective drug is available, the biochemist discards the bread from her sandwiches, and the mathematician indulges in designer chocolate with a clear conscience. The demographer sticks to vitamin supplements, and while the evolutionary biologist calculates the compensations of celibacy, the population biologist transplants gonads, but so far only those of his laboratory mice. Their common cause is to control and extend the healthy lifespan of humans. They want to cure ageing and the diseases that come with it. Larger organisms have more potentially carcinogenic cells, tend to live longer and require more ontogenic cell divisions. Therefore, intuitively one might expect cancer incidence to scale with body size. Evidence from mammals, however, suggests that the cancer risk does not correlate with body size. This observation defines “Peto’s paradox.”

Larger organisms have more potentially carcinogenic cells, tend to live longer and require more ontogenic cell divisions. Therefore, intuitively one might expect cancer incidence to scale with body size. Evidence from mammals, however, suggests that the cancer risk does not correlate with body size. This observation defines “Peto’s paradox.”