by Emrys Westacott

The coronavirus pandemic has massively disrupted the working lives of millions of people. For those who have lost their jobs, income, or work-related benefits, this can mean serious hardship and anxiety. For others, it has meant getting used to new routines and methods of working. For all of us, though, it should prompt reflection on how we think about work in general–both as a curse and as a blessing. Here, I want to focus on how work relates to time.

The coronavirus pandemic has massively disrupted the working lives of millions of people. For those who have lost their jobs, income, or work-related benefits, this can mean serious hardship and anxiety. For others, it has meant getting used to new routines and methods of working. For all of us, though, it should prompt reflection on how we think about work in general–both as a curse and as a blessing. Here, I want to focus on how work relates to time.

In ‘The Superannuated Man,’ Charles Lamb writes,

that is the only true Time, which a man can properly call his own, that which he has all to himself; the rest, though in some sense he may be said to live it, is other people’s times, not his.

This is a basic and obvious reason that many people resent having to go to work. Work takes up time, and time, as many sages have observed, is supremely valuable, irreplaceable, priceless. It is precious because we each know that we are granted only a limited amount of it.

Time is, in the words of Ben Franklin, “the stuff life is made of.” So insofar as work consumes your time, it consumes your life. If your work is what you really want to do, this is not a problem. But if much of the time when you are working–whether you are selling your services to someone else for an agreed number of hours, or drudging away at home–you would really prefer to be doing something else, then your working hours represent an enormous sacrifice. You are using up your supply of a decidedly finite, non-renewable resource. Read more »

Beauty has long been associated with moments in life that cannot easily be spoken of—what is often called “the ineffable”. When astonished or transfixed by nature, a work or art, or a bottle of wine, words even when finely voiced seem inadequate. Are words destined to fail? Can we not share anything of the experience of beauty? On the one hand, the experience of beauty is private; it is after all my experience not someone else’s. But, on the other hand, we seem to have a great need to share our experiences. Words fail but that doesn’t get us to shut up.

Beauty has long been associated with moments in life that cannot easily be spoken of—what is often called “the ineffable”. When astonished or transfixed by nature, a work or art, or a bottle of wine, words even when finely voiced seem inadequate. Are words destined to fail? Can we not share anything of the experience of beauty? On the one hand, the experience of beauty is private; it is after all my experience not someone else’s. But, on the other hand, we seem to have a great need to share our experiences. Words fail but that doesn’t get us to shut up. Jan Rubens was in love, and then he was on the run. Once the affair with Anna of Saxony was discovered and Jan was arrested, he ran back to his wife, Peter Paul’s mother, begging her for forgiveness and for help. Who knows what was in the man’s heart? Maybe the whole ordeal created deep within the soul of Jan Rubens a love of his wife that had never existed before. Maybe the fog of love was lifted from his eyes, the fog of lust cleared away and gone too was the clouding monomania that sets in when a married man runs into the arms of another woman. Maybe one passion had overtaken the mind of Jan Rubens as he fell into this desperate affair with Anna of Saxony, an otherwise difficult woman as the contemporary sources say, and it made him forget about the rest of the world. He started to see everything through the lens of this clawing need, the need to be with Anna of Saxony, the need to manufacture more and more reasons that he spend time with her, work on projects with her, center his life around her. This became a demanding and unforgiving logic. He stopped asking why, he stopped considering his life in any other light than the light of need. He needed to be with Anna of Saxony, dearest Anna, the only woman alive.

Jan Rubens was in love, and then he was on the run. Once the affair with Anna of Saxony was discovered and Jan was arrested, he ran back to his wife, Peter Paul’s mother, begging her for forgiveness and for help. Who knows what was in the man’s heart? Maybe the whole ordeal created deep within the soul of Jan Rubens a love of his wife that had never existed before. Maybe the fog of love was lifted from his eyes, the fog of lust cleared away and gone too was the clouding monomania that sets in when a married man runs into the arms of another woman. Maybe one passion had overtaken the mind of Jan Rubens as he fell into this desperate affair with Anna of Saxony, an otherwise difficult woman as the contemporary sources say, and it made him forget about the rest of the world. He started to see everything through the lens of this clawing need, the need to be with Anna of Saxony, the need to manufacture more and more reasons that he spend time with her, work on projects with her, center his life around her. This became a demanding and unforgiving logic. He stopped asking why, he stopped considering his life in any other light than the light of need. He needed to be with Anna of Saxony, dearest Anna, the only woman alive. Bemoaning uneven individual and state compliance with public health recommendations, top U.S. COVID-19 adviser Anthony Fauci

Bemoaning uneven individual and state compliance with public health recommendations, top U.S. COVID-19 adviser Anthony Fauci  According to the

According to the  When crew from CNN’s “Anthony Bourdain: Parts Unknown” contacted me in February 2014 to ask for assistance with an upcoming shoot in Thailand, of course I agreed without hesitation.

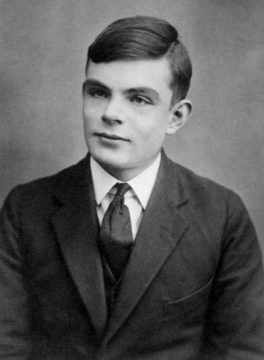

When crew from CNN’s “Anthony Bourdain: Parts Unknown” contacted me in February 2014 to ask for assistance with an upcoming shoot in Thailand, of course I agreed without hesitation. Alan Mathison Turing (1912 –1954) was one of England’s foremost mathematicians and computer scientists. Because of his work in artificial intelligence and codebreaking, along with his groundbreaking Enigma machine, he is credited with ending World War II. Turing’s life ended in tragedy. Convicted of “indecency” for his sexual orientation, Turing lost his security clearance, was chemically castrated, and later committed suicide at age 41.

Alan Mathison Turing (1912 –1954) was one of England’s foremost mathematicians and computer scientists. Because of his work in artificial intelligence and codebreaking, along with his groundbreaking Enigma machine, he is credited with ending World War II. Turing’s life ended in tragedy. Convicted of “indecency” for his sexual orientation, Turing lost his security clearance, was chemically castrated, and later committed suicide at age 41. In the first half of the 20th century, science fiction familiarized the world with the concept of artificially intelligent robots. It began with the “heartless” Tin man from the Wizard of Oz and continued with the humanoid robot that impersonated Maria in Metropolis. By the 1950s, we had a generation of scientists, mathematicians, and philosophers with the concept of artificial intelligence (or AI) culturally assimilated in their minds. One such person was Alan Turing, a young British polymath who explored the mathematical possibility of artificial intelligence. Turing suggested that humans use available information as well as reason in order to solve problems and make decisions, so why can’t machines do the same thing? This was the logical framework of his 1950 paper,

In the first half of the 20th century, science fiction familiarized the world with the concept of artificially intelligent robots. It began with the “heartless” Tin man from the Wizard of Oz and continued with the humanoid robot that impersonated Maria in Metropolis. By the 1950s, we had a generation of scientists, mathematicians, and philosophers with the concept of artificial intelligence (or AI) culturally assimilated in their minds. One such person was Alan Turing, a young British polymath who explored the mathematical possibility of artificial intelligence. Turing suggested that humans use available information as well as reason in order to solve problems and make decisions, so why can’t machines do the same thing? This was the logical framework of his 1950 paper,  Above all, Cockayne wants us to revise our assumption that people in the past must have been better at reuse and recycling (not the same thing) than we are today. There is, she insists, “no linear history of improvement”, no golden age when everyone automatically sorted their household scraps and spent their evenings turning swords into ploughshares because they knew it was the right thing to do. Indeed, in the 1530s the more stuff you threw away, the better you were performing your civic duty: refuse and surfeit was built into the semiotics of display in Henry VIII’s England, which explains why, on formal occasions, it was stylish to have claret and white wine running down the gutters. Three generations later and Oliver Cromwell’s Parliamentarian troops had found new ways to manipulate codes of waste and value. In 1646 they ransacked Winchester cathedral and sent all the precious parchments off to London to be made into kites “withal to fly in the air”.

Above all, Cockayne wants us to revise our assumption that people in the past must have been better at reuse and recycling (not the same thing) than we are today. There is, she insists, “no linear history of improvement”, no golden age when everyone automatically sorted their household scraps and spent their evenings turning swords into ploughshares because they knew it was the right thing to do. Indeed, in the 1530s the more stuff you threw away, the better you were performing your civic duty: refuse and surfeit was built into the semiotics of display in Henry VIII’s England, which explains why, on formal occasions, it was stylish to have claret and white wine running down the gutters. Three generations later and Oliver Cromwell’s Parliamentarian troops had found new ways to manipulate codes of waste and value. In 1646 they ransacked Winchester cathedral and sent all the precious parchments off to London to be made into kites “withal to fly in the air”. Dickinson said her life had not been constrained or dreary in any way. “I find ecstasy in living,” she explained. The “mere sense of living is joy enough.” When at last the opportunity arose, Higginson posed the question he most wanted to ask: Did you ever want a job, have a desire to travel or see people? The question unleashed a forceful reply. “I never thought of conceiving that I could ever have the slightest approach to such a want in all future time.” Then she loaded on more. “I feel that I have not expressed myself strongly enough.” Dickinson reserved her most striking statement for what poetry meant to her, or, rather, how it made her feel. “If I read a book [and] it makes my whole body so cold no fire can ever warm me I know that is poetry,” she said. “If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry. These are the only way I know it. Is there any other way.” Dickinson was remarkable. Brilliant. Candid. Deliberate. Mystifying. After eight years of waiting, Higginson was finally sitting across from Emily Dickinson of Amherst, and all he wanted to do was listen.

Dickinson said her life had not been constrained or dreary in any way. “I find ecstasy in living,” she explained. The “mere sense of living is joy enough.” When at last the opportunity arose, Higginson posed the question he most wanted to ask: Did you ever want a job, have a desire to travel or see people? The question unleashed a forceful reply. “I never thought of conceiving that I could ever have the slightest approach to such a want in all future time.” Then she loaded on more. “I feel that I have not expressed myself strongly enough.” Dickinson reserved her most striking statement for what poetry meant to her, or, rather, how it made her feel. “If I read a book [and] it makes my whole body so cold no fire can ever warm me I know that is poetry,” she said. “If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry. These are the only way I know it. Is there any other way.” Dickinson was remarkable. Brilliant. Candid. Deliberate. Mystifying. After eight years of waiting, Higginson was finally sitting across from Emily Dickinson of Amherst, and all he wanted to do was listen. S. Jones and Stefan Helmreich in Boston Review (figure from From Kristine Moore et al., “

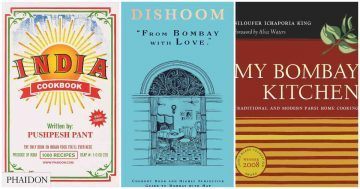

S. Jones and Stefan Helmreich in Boston Review (figure from From Kristine Moore et al., “ Aparna Kapadia in Scroll.in:

Aparna Kapadia in Scroll.in: Cate Lineberry over at Smithsonian Magazine:

Cate Lineberry over at Smithsonian Magazine:

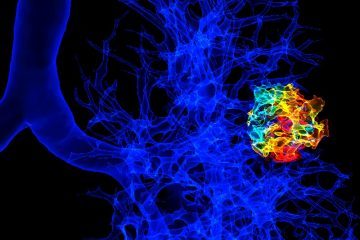

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the TRACERx project had recruited 760 people with early-stage lung cancer. After a person is diagnosed with a primary lung tumour, it is surgically removed and the cells are analysed to reconstruct the tumour’s evolutionary history. Each individual receives a computed tomography (CT) scan every year for five years to check whether their cancer has returned. If there is no sign of relapse, they are discharged and deemed to have been cured. People with later-stage tumours (stages 2 and 3) are offered chemotherapy following surgery to improve the chance of remission or cure.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the TRACERx project had recruited 760 people with early-stage lung cancer. After a person is diagnosed with a primary lung tumour, it is surgically removed and the cells are analysed to reconstruct the tumour’s evolutionary history. Each individual receives a computed tomography (CT) scan every year for five years to check whether their cancer has returned. If there is no sign of relapse, they are discharged and deemed to have been cured. People with later-stage tumours (stages 2 and 3) are offered chemotherapy following surgery to improve the chance of remission or cure.