Joshua Hunt in The Economist:

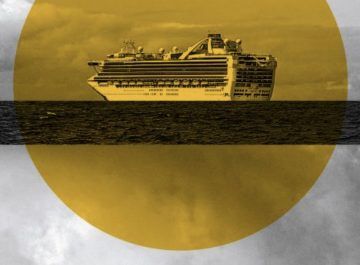

The Diamond Princess has a steakhouse, a pizzeria and restaurants specialising in sushi and Italian cuisine. Buffets offer prime rib, escargots and crème brûlée, all served in gigantic portions at every hour of the day or night. The ship has its own mixologist, sommelier and chocolatier.

The Diamond Princess has a steakhouse, a pizzeria and restaurants specialising in sushi and Italian cuisine. Buffets offer prime rib, escargots and crème brûlée, all served in gigantic portions at every hour of the day or night. The ship has its own mixologist, sommelier and chocolatier.

The Diamond Princess is one of about 300 cruise ships that circle the globe each year. Last year they carried 30m passengers through holidays that seem to belong to another time, before travellers prized authenticity over luxury, sustainability over excess and adventure over sedentary stimulation. However outdated the cruise experience may seem, more passengers are enjoying it than ever before. Last year Carnival Corporation, the world’s largest cruise-ship conglomerate, which owns Princess Cruises along with eight other lines and carries half the world’s cruise passengers each year, brought in record-setting revenues of $21bn.

More here.

History, literature, film, and scripture are loaded with stories and examples of redemption. Buddhism gives us the story of Aṅgulimāla, a pathological mass-murderer who became a follower of the Buddha and went on to be enshrined as a “patron saint” of childbirth in South and Southeast Asia. Rick Blaine, the character played by Humphrey Bogart in the 1942 Hollywood classic Casablanca, put side his cynical bitterness and seeming indifference to the rise of the Nazi Third Reich to help Isla Lund (played by Ingmar Bergman) – the former lover who jilted (and embittered) him – escape the grip of the Nazis with her husband, an anti-fascist Resistance fighter. The movie ends with Blaine declaring his determination to join the Resistance in Morocco. The New Testament tells the story of Zacchaeus, a chief tax collector and a wealthy man:

History, literature, film, and scripture are loaded with stories and examples of redemption. Buddhism gives us the story of Aṅgulimāla, a pathological mass-murderer who became a follower of the Buddha and went on to be enshrined as a “patron saint” of childbirth in South and Southeast Asia. Rick Blaine, the character played by Humphrey Bogart in the 1942 Hollywood classic Casablanca, put side his cynical bitterness and seeming indifference to the rise of the Nazi Third Reich to help Isla Lund (played by Ingmar Bergman) – the former lover who jilted (and embittered) him – escape the grip of the Nazis with her husband, an anti-fascist Resistance fighter. The movie ends with Blaine declaring his determination to join the Resistance in Morocco. The New Testament tells the story of Zacchaeus, a chief tax collector and a wealthy man: There is perhaps no better individual showcase of The Beatles’ infinite variety than the “Yellow Submarine”/“Eleanor Rigby” double A-side record released on August 5 1966. One single was

There is perhaps no better individual showcase of The Beatles’ infinite variety than the “Yellow Submarine”/“Eleanor Rigby” double A-side record released on August 5 1966. One single was  Rajan Roy in Margins:

Rajan Roy in Margins: Hal Foster in Lit Hub

Hal Foster in Lit Hub Corey Robin in The Nation:

Corey Robin in The Nation:

If oppositional art can neither parody nor demystify the operation of power, what glimpses of the future can it provide? Whereas Foster’s previous books surveyed the art scene by identifying a small number of key trends, his approach here is more scattergun: we get 18 telegraphic essays on as many artists, whose work is used to illustrate competing forces in the culture industry. This kaleidoscopic perspective has its pitfalls. Breadth of analysis is often privileged over depth of insight. Sculptors, painters, conceptual artists and cultural theorists all make cameo appearances, yet the links between their work go unelaborated. Even so, the rapid pace of Foster’s prose captures the frenzied historical moment he is exploring; and his reluctance to offer simple answers acknowledges that multiple possibilities for reshaping our culture are currently ranged against each other.

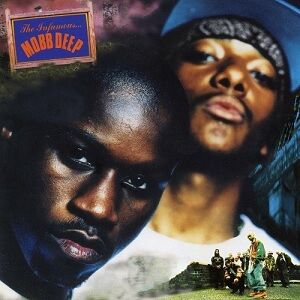

If oppositional art can neither parody nor demystify the operation of power, what glimpses of the future can it provide? Whereas Foster’s previous books surveyed the art scene by identifying a small number of key trends, his approach here is more scattergun: we get 18 telegraphic essays on as many artists, whose work is used to illustrate competing forces in the culture industry. This kaleidoscopic perspective has its pitfalls. Breadth of analysis is often privileged over depth of insight. Sculptors, painters, conceptual artists and cultural theorists all make cameo appearances, yet the links between their work go unelaborated. Even so, the rapid pace of Foster’s prose captures the frenzied historical moment he is exploring; and his reluctance to offer simple answers acknowledges that multiple possibilities for reshaping our culture are currently ranged against each other. IN THE FALL of 1994, American radio and club DJs began receiving a promotional single in the mail: “Shook Ones, Pt. II,” by the Queens rap duo Mobb Deep. Those early promos came with little fanfare — no cover art, no liner notes, just a plain center sticker with the group’s name, song title, and record label logo. The reaction to “Shook Ones, Pt. II” was as spectacular as its arrival was understated. Its dark, discordant track and violent braggadocio powered the single onto hip-hop mix shows, and the song sparked fights in rowdier nightclubs whenever it rumbled over the speakers. Eminem’s hit 2002 film 8 Mile paid “Shook Ones, Pt. II” the ultimate homage by using it in the film’s cold open, a shot of auditory adrenaline jabbed into the heart of B-Rabbit as he prepares for an MC battle.

IN THE FALL of 1994, American radio and club DJs began receiving a promotional single in the mail: “Shook Ones, Pt. II,” by the Queens rap duo Mobb Deep. Those early promos came with little fanfare — no cover art, no liner notes, just a plain center sticker with the group’s name, song title, and record label logo. The reaction to “Shook Ones, Pt. II” was as spectacular as its arrival was understated. Its dark, discordant track and violent braggadocio powered the single onto hip-hop mix shows, and the song sparked fights in rowdier nightclubs whenever it rumbled over the speakers. Eminem’s hit 2002 film 8 Mile paid “Shook Ones, Pt. II” the ultimate homage by using it in the film’s cold open, a shot of auditory adrenaline jabbed into the heart of B-Rabbit as he prepares for an MC battle. IF THE TRUMP ADMINISTRATION

IF THE TRUMP ADMINISTRATION  Over the past month, Jennifer Leiferman, a researcher at the Colorado School of Public Health, has documented a tidal wave of depressive symptoms in the U.S. “The rates we’re seeing are just so much higher than normal,” she says. Leiferman’s team recently

Over the past month, Jennifer Leiferman, a researcher at the Colorado School of Public Health, has documented a tidal wave of depressive symptoms in the U.S. “The rates we’re seeing are just so much higher than normal,” she says. Leiferman’s team recently  For those doubtful about the fascism analogy for Trumpism—and I count myself as one of them—the point is to appreciate both continuity and novelty better than the comparison allows. Abnormalizing Trump disguises that he is quintessentially American, the expression of enduring and indigenous syndromes. A response to what he represents hardly requires a restoration of “normalcy” but a questioning of the status quo ante Trump that produced him. Comparison to Nazism and fascism imminently threatening to topple democracy distracts us from how we made Trump over decades, and implies that the coexistence of our democracy with long histories of killing, subjugation, and terror—including its most recent, if somewhat sanitized, forms of mass incarceration and rising inequality at home, and its tenuous empire and regular war-making abroad—was somehow less worth the alarm and opprobrium. Selective outrage after 2016 says more about the outraged than the outrageous.

For those doubtful about the fascism analogy for Trumpism—and I count myself as one of them—the point is to appreciate both continuity and novelty better than the comparison allows. Abnormalizing Trump disguises that he is quintessentially American, the expression of enduring and indigenous syndromes. A response to what he represents hardly requires a restoration of “normalcy” but a questioning of the status quo ante Trump that produced him. Comparison to Nazism and fascism imminently threatening to topple democracy distracts us from how we made Trump over decades, and implies that the coexistence of our democracy with long histories of killing, subjugation, and terror—including its most recent, if somewhat sanitized, forms of mass incarceration and rising inequality at home, and its tenuous empire and regular war-making abroad—was somehow less worth the alarm and opprobrium. Selective outrage after 2016 says more about the outraged than the outrageous.