Aida Edemariam in The Guardian:

Virginia Woolf, aged 23, recently orphaned and still 10 years away from publishing her debut novel, was first commissioned to write reviews for the TLS in 1905. She began, as Francesca Wade points out in her preface to this collection, like any novice – by reviewing anything the editors sent her: guide books, cookery books, poetry, debut novels. Often she was filing a piece a week, reading the book on Sunday, writing – in the anonymous, authoritative TLS first-person plural “we” – up to 1,500 words on Monday, to be printed on Friday. The reviews gave her independence, and they made her a writer.

Virginia Woolf, aged 23, recently orphaned and still 10 years away from publishing her debut novel, was first commissioned to write reviews for the TLS in 1905. She began, as Francesca Wade points out in her preface to this collection, like any novice – by reviewing anything the editors sent her: guide books, cookery books, poetry, debut novels. Often she was filing a piece a week, reading the book on Sunday, writing – in the anonymous, authoritative TLS first-person plural “we” – up to 1,500 words on Monday, to be printed on Friday. The reviews gave her independence, and they made her a writer.

Through these pieces she “learnt a lot of my craft”, she once recalled; “how to compress; how to enliven”, how “to read with a pen & notebook, seriously”. She could not of course have managed it without a childhood of reading (“the great season for reading is the season between the ages of18 and 24”, as she puts it, somewhat archly, in “Hours in a Library”). Also essential was the cultural capital she took for granted as the daughter of leading man of letters Leslie Stephen (and which she recognises as a foundation of Fanny Burney’s work: “all the stimulus that comes from running in and out of rooms where grown-up people are talking about books and music”). She possessed the journalist’s and then the novelist’s gift for detail (the 107 dinner parties Henry James attended in one season, for instance, without being appreciably impressed by any of them), and the humility, at least at first, to understand that she must earn the attention of “busy people catching trains in the mornings” and “tired people coming home in the evening”.

She was working out, too, what being a critic meant. ‘A great critic” – a “Coleridge, above all” – “is the rarest of beings” she believed; what’s more, he wrote of drama and of poetry. The criticism of fiction “is in its infancy”, she wrote. This was an opportunity, but also a challenge – for where, as a young woman, and an autodidact, did she fit in? That gender-ambiguous “we” sometimes feels like a cloak swept about her with too much bravado.

More here.

For at least a decade now there’s been a buzz about Mark Bradford. People call him an exciting painter. Those two words, “exciting” and “painting,” don’t get put together very often, which is understandable. There is something about painting that promotes a reflective attitude. You look at a painting by standing your distance and contemplating. You can like a painting, love a painting, even be moved by a painting. But excitement? Not so much. What is it about Bradford’s paintings that makes them exciting? The answer, I think, is that Bradford has discovered an approach to abstraction that’s genuinely fresh, genuinely new. No one’s done it quite like this before.

For at least a decade now there’s been a buzz about Mark Bradford. People call him an exciting painter. Those two words, “exciting” and “painting,” don’t get put together very often, which is understandable. There is something about painting that promotes a reflective attitude. You look at a painting by standing your distance and contemplating. You can like a painting, love a painting, even be moved by a painting. But excitement? Not so much. What is it about Bradford’s paintings that makes them exciting? The answer, I think, is that Bradford has discovered an approach to abstraction that’s genuinely fresh, genuinely new. No one’s done it quite like this before. A large number of well done studies have painted a rather consistent picture of sex differences in personality that are strikingly consistent across cultures (see

A large number of well done studies have painted a rather consistent picture of sex differences in personality that are strikingly consistent across cultures (see  Benton was massively popular in his heyday. This Is My Beloved came out in 1943; Billboard reported in early 1949 that the book had sold more than 350,000 copies, and it remained continuously in print for decades. Benton’s work appeared in the Yale Review, Esquire, the New Republic, Poetry, and other prestigious outlets, but he’s best remembered today (if at all) for his World War II poetry. The only contemporary review of This Is My Beloved I could track down was in Kirkus Reviews in 1942. It’s a wry, saucy write-up that reads: “High voltage verse, this, in free verse for a sequence of lyrics commemorating a love affair and its termination. Intimate corporeal and physical detail and extravagant praise thereof, in what might mildly be termed erotica.

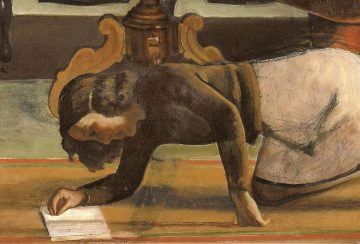

Benton was massively popular in his heyday. This Is My Beloved came out in 1943; Billboard reported in early 1949 that the book had sold more than 350,000 copies, and it remained continuously in print for decades. Benton’s work appeared in the Yale Review, Esquire, the New Republic, Poetry, and other prestigious outlets, but he’s best remembered today (if at all) for his World War II poetry. The only contemporary review of This Is My Beloved I could track down was in Kirkus Reviews in 1942. It’s a wry, saucy write-up that reads: “High voltage verse, this, in free verse for a sequence of lyrics commemorating a love affair and its termination. Intimate corporeal and physical detail and extravagant praise thereof, in what might mildly be termed erotica.  When I was a child, there was a book about the Polish artist Balthus in the small library at our country home. It was dad’s book, big and heavy. The skin between my thumb and index finger stretched taut when I took it down from the shelf. Sometimes I would sit at the table there in the library and page through the book. The table was by a window that looked out on a forest of firs. The light from the window was dim and pale; it seemed to lack strength and direction.

When I was a child, there was a book about the Polish artist Balthus in the small library at our country home. It was dad’s book, big and heavy. The skin between my thumb and index finger stretched taut when I took it down from the shelf. Sometimes I would sit at the table there in the library and page through the book. The table was by a window that looked out on a forest of firs. The light from the window was dim and pale; it seemed to lack strength and direction. When Guy Partnerman and Lady Millionaire purchased a brownstone in the most Brooklyn-themed neighborhood of Brooklyn, there was only one drawback: the home was too beautiful.

When Guy Partnerman and Lady Millionaire purchased a brownstone in the most Brooklyn-themed neighborhood of Brooklyn, there was only one drawback: the home was too beautiful.

p53 is the most famous cancer gene, not least because it’s involved in causing over 50% of all cancers. When a cell loses its p53 gene—when the gene becomes mutated—it unleashes many processes that lead to the uncontrolled cell growth and refusal to die, which are hallmarks of cancer growth. But there are some cancers, like kidney cancer, that that had few p53 mutations. In order to understand whether the inactivation of the p53 pathway might contribute to kidney cancer development, Haifang Yang, Ph.D., a researcher with the Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center—Jefferson Health probed kidney cancer’s genes for interactions with p53.

p53 is the most famous cancer gene, not least because it’s involved in causing over 50% of all cancers. When a cell loses its p53 gene—when the gene becomes mutated—it unleashes many processes that lead to the uncontrolled cell growth and refusal to die, which are hallmarks of cancer growth. But there are some cancers, like kidney cancer, that that had few p53 mutations. In order to understand whether the inactivation of the p53 pathway might contribute to kidney cancer development, Haifang Yang, Ph.D., a researcher with the Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center—Jefferson Health probed kidney cancer’s genes for interactions with p53. Humans boast a rich trove of words to express the way we feel. Some are not easily translatable between languages: Germans use “Weltschmerz” to refer to a feeling of melancholy caused by the state of the world. And the indigenous Baining people of Papua New Guinea say “awumbuk” to describe a social hangover that leaves people unmotivated and listless for days after the departure of overnight guests. Other terms seem rather common—“fear,” for example, translates to “takot” in Tagalog and “ótti” in Icelandic. These similarities and differences raise a question: Does the way we experience emotions cross cultural boundaries?

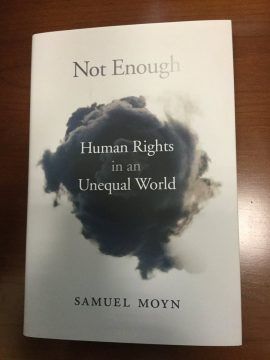

Humans boast a rich trove of words to express the way we feel. Some are not easily translatable between languages: Germans use “Weltschmerz” to refer to a feeling of melancholy caused by the state of the world. And the indigenous Baining people of Papua New Guinea say “awumbuk” to describe a social hangover that leaves people unmotivated and listless for days after the departure of overnight guests. Other terms seem rather common—“fear,” for example, translates to “takot” in Tagalog and “ótti” in Icelandic. These similarities and differences raise a question: Does the way we experience emotions cross cultural boundaries? In Not Enough, Samuel Moyn addresses a disjunction between the language of human rights and the facts of inequality. Our unequal world, Moyn observes, is one in which the rich have grown ever richer, but the poor have remained poor, or, at best, not quite as poor as they once were. The language of human rights may not have been the cause of economic inequality, he argues, but neither has it done much to prevent it. Moyn, a professor of law and history at Yale University, draws upon a wide range of sources in making his claims: nineteenth-century debates about distributive ethics, eighteenth-century Jacobin texts and treatises, medieval and ancient sources. Moyn also considers more recent events that have long been associated with the history of human rights: Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Second Bill of Rights; the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; and later efforts to emphasize material equality and social justice in the context of decolonization. These efforts, Moyn believes, were too easily assimilated in welfare states, or outpaced in others. They converted none to the cause.

In Not Enough, Samuel Moyn addresses a disjunction between the language of human rights and the facts of inequality. Our unequal world, Moyn observes, is one in which the rich have grown ever richer, but the poor have remained poor, or, at best, not quite as poor as they once were. The language of human rights may not have been the cause of economic inequality, he argues, but neither has it done much to prevent it. Moyn, a professor of law and history at Yale University, draws upon a wide range of sources in making his claims: nineteenth-century debates about distributive ethics, eighteenth-century Jacobin texts and treatises, medieval and ancient sources. Moyn also considers more recent events that have long been associated with the history of human rights: Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Second Bill of Rights; the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; and later efforts to emphasize material equality and social justice in the context of decolonization. These efforts, Moyn believes, were too easily assimilated in welfare states, or outpaced in others. They converted none to the cause. Twenty-six years into the war, a harsh assessment

Twenty-six years into the war, a harsh assessment  In January 2018, Russia secretly launched a cruise missile powered by a small nuclear reactor at a military testing range in the northern region of Arkhangelsk. The test of this bizarre doomsday weapon was a failure—it landed in the sea just a few kilometres from the launch site. The test would have remained a secret, but in August 2019 Russian scientists attempted to lift the wreckage off the Arctic seafloor. There was an explosion—one powerful enough to be detected by monitoring stations in Finland, Norway and Sweden. Five scientists were killed and a brief spike of radiation was detected in the nearby city of Severodvinsk. Images on social media showed emergency service workers responding in Hazmat suits. The Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban treaty Organisation, the body charged with detecting nuclear explosions, predicted that any plume of radionuclides from the accident would soon drift over monitoring stations in central Russia. Then those stations mysteriously stopped working. Viewers of the drama series Chernobyl might not have been surprised.

In January 2018, Russia secretly launched a cruise missile powered by a small nuclear reactor at a military testing range in the northern region of Arkhangelsk. The test of this bizarre doomsday weapon was a failure—it landed in the sea just a few kilometres from the launch site. The test would have remained a secret, but in August 2019 Russian scientists attempted to lift the wreckage off the Arctic seafloor. There was an explosion—one powerful enough to be detected by monitoring stations in Finland, Norway and Sweden. Five scientists were killed and a brief spike of radiation was detected in the nearby city of Severodvinsk. Images on social media showed emergency service workers responding in Hazmat suits. The Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban treaty Organisation, the body charged with detecting nuclear explosions, predicted that any plume of radionuclides from the accident would soon drift over monitoring stations in central Russia. Then those stations mysteriously stopped working. Viewers of the drama series Chernobyl might not have been surprised. Lutz’s stories are resistant to summary, not because nothing happens in them, but because it can be difficult to decipher what does. For Lutz, narrative is a by-product of language, not the other way around, and it unfolds musically rather than logically, resulting in sharp shifts and turns that are hard to track. I’m pretty sure, for example, that one story involves a man being fitted for dentures made in the molds of houses he lived in as a child, but I wouldn’t put money on it. I’m slightly more confident that another involves the use of a tennis racket in a backroom orchiectomy. The opacity is by design. These stories glory in language, but Lutz also seems to suggest that it’s an insufficient tool for representing experience. Characters constantly worry they’re not providing the right details or explaining things correctly. Their statements are subject to endless retractions and qualifications, and their cataloguing and quantifying never quite add up. The linguistic acrobatics can be read, in part, as a futile rebuff against the limits of expression.

Lutz’s stories are resistant to summary, not because nothing happens in them, but because it can be difficult to decipher what does. For Lutz, narrative is a by-product of language, not the other way around, and it unfolds musically rather than logically, resulting in sharp shifts and turns that are hard to track. I’m pretty sure, for example, that one story involves a man being fitted for dentures made in the molds of houses he lived in as a child, but I wouldn’t put money on it. I’m slightly more confident that another involves the use of a tennis racket in a backroom orchiectomy. The opacity is by design. These stories glory in language, but Lutz also seems to suggest that it’s an insufficient tool for representing experience. Characters constantly worry they’re not providing the right details or explaining things correctly. Their statements are subject to endless retractions and qualifications, and their cataloguing and quantifying never quite add up. The linguistic acrobatics can be read, in part, as a futile rebuff against the limits of expression. Graduate school is psychologically punishing for people in every field, not just for people who worry that their topic is especially ineffectual. The more you read, the more you realize you should have read already. But philosophy’s claim to despair is unique. As Stanley Cavell writes in the introduction to

Graduate school is psychologically punishing for people in every field, not just for people who worry that their topic is especially ineffectual. The more you read, the more you realize you should have read already. But philosophy’s claim to despair is unique. As Stanley Cavell writes in the introduction to  What is the language of the internet? Most of us have probably heard of LOL (or lol), omg, emojis and even memes, and come face to face with unconventional confections of exclamation marks, repeated letters and novelty punctuation. For people like us, top-end book lovers, the language of the internet might seem, well, rather ghastly: illiterate, limited, debased, invasive like Japanese knotweed, a frightful triffid threatening to obliterate decent standards of communication. They, the internet lovers, if they even bother to glance in our direction, will think: omg!!!!11!!! sad lol.

What is the language of the internet? Most of us have probably heard of LOL (or lol), omg, emojis and even memes, and come face to face with unconventional confections of exclamation marks, repeated letters and novelty punctuation. For people like us, top-end book lovers, the language of the internet might seem, well, rather ghastly: illiterate, limited, debased, invasive like Japanese knotweed, a frightful triffid threatening to obliterate decent standards of communication. They, the internet lovers, if they even bother to glance in our direction, will think: omg!!!!11!!! sad lol. Maya Angelou published the first of her seven memoirs not long after she distinguished herself as the star raconteur at a dinner party. “At the time, I was really only concerned with poetry, though I had written a television series,” she would recall. James Baldwin, the novelist and activist, took her to the party, which was at the home of the cartoonist-writer Jules Feiffer and his then-wife, Judy. “We enjoyed each other immensely and sat up until 3 or 4 in the morning, drinking Scotch and telling tales,” Angelou went on. “The next morning, Judy Feiffer called a friend of hers at Random House and said, ‘You know the poet Maya Angelou? If you could get her to write a book…’” That book became

Maya Angelou published the first of her seven memoirs not long after she distinguished herself as the star raconteur at a dinner party. “At the time, I was really only concerned with poetry, though I had written a television series,” she would recall. James Baldwin, the novelist and activist, took her to the party, which was at the home of the cartoonist-writer Jules Feiffer and his then-wife, Judy. “We enjoyed each other immensely and sat up until 3 or 4 in the morning, drinking Scotch and telling tales,” Angelou went on. “The next morning, Judy Feiffer called a friend of hers at Random House and said, ‘You know the poet Maya Angelou? If you could get her to write a book…’” That book became