Cecilia Vicuña. Quipu Womb (The Story of the Red Thread, Athens), 2017.

Dyed wool; Documenta 14.

by Anitra Pavlico

There is only one healing force, and that is nature. —Arthur Schopenhauer

The Biophilia Effect: A Scientific and Spiritual Exploration of the Healing Bond Between Humans and Nature, by Austrian biologist Clemens G. Arvay, is a mind-expanding read. It is part of the relatively recent resurgence of interest in incorporating exposure to nature into physical and psychological healing regimens. Until recently, the notion of “taking the cure” by relaxing at a Swiss resort in a natural setting was seen as archaic, thought to have been prescribed only because medicine had not advanced to a point where a “real” treatment could be used. Not that everyone had abandoned the idea: Erich Fromm used the term “biophilia” in his 1973 work The Anatomy of Human Destructiveness to describe “the passionate love of life and of all that is alive.” American biologist Edward O. Wilson published Biophilia in 1984, positing genetic bases for humans’ tendency to gravitate to nature. Now scientists en masse are studying nature’s extraordinary healing effects. In Japan, shinrin-yoku–“taking in the forest atmosphere,” or as it is more often translated in the West, “forest bathing”– is officially recognized as a method of preventing disease as well as a supplement to treatment. In 2012, Japanese universities created an independent medical research department called Forest Medicine. Scientists around the world have begun to participate in this research.

The Biophilia Effect: A Scientific and Spiritual Exploration of the Healing Bond Between Humans and Nature, by Austrian biologist Clemens G. Arvay, is a mind-expanding read. It is part of the relatively recent resurgence of interest in incorporating exposure to nature into physical and psychological healing regimens. Until recently, the notion of “taking the cure” by relaxing at a Swiss resort in a natural setting was seen as archaic, thought to have been prescribed only because medicine had not advanced to a point where a “real” treatment could be used. Not that everyone had abandoned the idea: Erich Fromm used the term “biophilia” in his 1973 work The Anatomy of Human Destructiveness to describe “the passionate love of life and of all that is alive.” American biologist Edward O. Wilson published Biophilia in 1984, positing genetic bases for humans’ tendency to gravitate to nature. Now scientists en masse are studying nature’s extraordinary healing effects. In Japan, shinrin-yoku–“taking in the forest atmosphere,” or as it is more often translated in the West, “forest bathing”– is officially recognized as a method of preventing disease as well as a supplement to treatment. In 2012, Japanese universities created an independent medical research department called Forest Medicine. Scientists around the world have begun to participate in this research.

Arvay writes that “Plants, like insects, communicate using chemical substances. They send out molecules . . . [that] can definitely be compared with a human language because, just like our words, they carry certain meaning in the world of plants and, therefore, information — a ‘plant vocabulary.’” Plants emit substances called terpenes, secondary plant compounds with almost forty thousand representatives that fulfill numerous functions. For example, plants emit terpenes as a sunscreen (you may be able to see terpenes forming a blue haze above a forest on a hot day). Plants also use terpenes to attract insects or other animals when they need their services, or to warn other plants about pests so that they can mobilize their immune systems. Plants also produce terpenes as a toxin to kill pests or deter predators. Read more »

Renata Pasqualini, is the Chief, Division of Cancer Biology, Department of Radiation Oncology at Rutgers Cancer Institute and Rutgers New Jersey Medical School having previously served as Associate Director for Translational Research and Chief of the Division of Molecular Medicine at the University of New Mexico Comprehensive Cancer Center. She has published more than 200 joint peer-reviewed research manuscripts and have more than 100 patents filed worldwide. Dr. Pasqualini’s lab discovered Prohibitin-TP01 which specifically targets the vasculature that nourishes white fat, a critical contributing factor in poor prostate cancer outcome. Preclinical studies in mouse models showed that TP01 treatment reduced white fat and resulted in ~30% weight reduction. Her goal is to successfully translate Prohibitin-TP01 into the clinic as a new agent for obese men with advanced prostate cancer.

Azra Raza, author of the forthcoming book The First Cell: And the Human Costs of Pursuing Cancer to the Last, oncologist and professor of medicine at Columbia University, and 3QD editor, decided to speak to more than 20 leading cancer investigators and ask each of them the same five questions listed below. She videotaped the interviews and over the next months we will be posting them here one at a time each Monday. Please keep in mind that Azra and the rest of us at 3QD neither endorse nor oppose any of the answers given by the researchers as part of this project. Their views are their own. One can browse all previous interviews here.

1. We were treating acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with 7+3 (7 days of the drug cytosine arabinoside and 3 days of daunomycin) in 1977. We are still doing the same in 2019. What is the best way forward to change it by 2028?

2. There are 3.5 million papers on cancer, 135,000 in 2017 alone. There is a staggering disconnect between great scientific insights and translation to improved therapy. What are we doing wrong?

3. The fact that children respond to the same treatment better than adults seems to suggest that the cancer biology is different and also that the host is different. Since most cancers increase with age, even having good therapy may not matter as the host is decrepit. Solution?

4. You have great knowledge and experience in the field. If you were given limitless resources to plan a cure for cancer, what will you do?

5. Offering patients with advanced stage non-curable cancer, palliative but toxic treatments is a service or disservice in the current therapeutic landscape?

by Elizabeth S. Bernstein

If we find that society values the traits and skills that are associated with being male and devalues the traits and skills that are associated with being female, then it is time to rethink societal values instead of denying the existence of biologically based male-female differences. —Diane F. Halpern, Sex Differences in Cognitive Abilities (2012)

Two months ago I wrote about the gender wage gap in the United States, and the fact that the careers of women vary from men’s in ways which align with the values which women express. Compared with men, women rank helping people higher and maximizing earnings lower. They express less willingness to commit actions which may harm others for the sake of profit. Their tendency to emphasize interpersonal relationships is reflected not only in the paid work they engage in, but also in the greater likelihood that they will reduce or exit employment to care for children or other family members.

Two months ago I wrote about the gender wage gap in the United States, and the fact that the careers of women vary from men’s in ways which align with the values which women express. Compared with men, women rank helping people higher and maximizing earnings lower. They express less willingness to commit actions which may harm others for the sake of profit. Their tendency to emphasize interpersonal relationships is reflected not only in the paid work they engage in, but also in the greater likelihood that they will reduce or exit employment to care for children or other family members.

While writing the piece I read a great deal of online commentary. There was the occasional nod towards the possibility that biology had something to do with the different inclinations on which men and women were acting. Far more common, though, were the explanations which pointed to women’s actions being steered by extrinsic forces – “social norms and expectations” that women will care for family members, “multitude of messages that women get from society about what sorts of jobs they should pick,” “the way that society views the bond between mothers and their children,” “unique socialization histories which instill more negative reactions to ethical compromises,” “persistence of stereotypes that drive women toward service labor.”

The emphasis on expectations and socialization over biology is hardly surprising. As the sociologists Shannon Davis and Barbara Risman write in their article “Feminists wrestle with testosterone: Hormones, socialization and cultural interactionism as predictors of women’s gendered selves,” feminists “worry that any nod of the head to biology will backfire.” Still, the conclusion of Davis and Risman’s own study was that both culture and biology (specifically exposure to prenatal hormones) influenced the degree to which women’s personalities evidenced “masculinity” or “femininity” (the latter of which the researchers suggest might better be called “nurturance and empathy”). There is no logical reason, Davis and Risman write, that feminists should deny that biology “shapes some part of our personality structure,” but neither should that justify “providing differential opportunities, constraints, and privileges to women and men.” Read more »

by Adele A Wilby

Many feminists, and indeed scholars more generally, frequently, and rightly, decry the writing of women out of history. Books such as Cathy Newman’s Bloody Brilliant Women, attempt to redress the historical omission and accord recognition to women who have made major contributions to the progress of humanity. However, while these developments are to be welcomed, it has to be acknowledged that women’s history has its darker side also: women have been complicit in the perpetration of historical wrongs. Sarah Helm’s If This Is A Woman documents the dehumanisation of female prisoners by female guards at the notorious all woman concentration camp at Ravensbrück during World War II; Laura Sjoberg and Caron E. Gentry’s Mothers, Monsters, Whores: Women’s Violence in Global Politics points out the potential of women to support and participate in acts of genocide. And, as Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers’s They Were Her Property: White Women as Slave Owners in the American South informs us, women were deeply involved in another historical wrong: slavery in the United States. Women were, as Jones-Rogers’ says, ‘co-conspirators’ in the institution of slavery in the US, and their involvement constitutes an aspect of the wider history of white supremacist organisations in the US.

Many feminists, and indeed scholars more generally, frequently, and rightly, decry the writing of women out of history. Books such as Cathy Newman’s Bloody Brilliant Women, attempt to redress the historical omission and accord recognition to women who have made major contributions to the progress of humanity. However, while these developments are to be welcomed, it has to be acknowledged that women’s history has its darker side also: women have been complicit in the perpetration of historical wrongs. Sarah Helm’s If This Is A Woman documents the dehumanisation of female prisoners by female guards at the notorious all woman concentration camp at Ravensbrück during World War II; Laura Sjoberg and Caron E. Gentry’s Mothers, Monsters, Whores: Women’s Violence in Global Politics points out the potential of women to support and participate in acts of genocide. And, as Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers’s They Were Her Property: White Women as Slave Owners in the American South informs us, women were deeply involved in another historical wrong: slavery in the United States. Women were, as Jones-Rogers’ says, ‘co-conspirators’ in the institution of slavery in the US, and their involvement constitutes an aspect of the wider history of white supremacist organisations in the US.

Jones-Rogers lays to rest any assumption that the trading and ownership of enslaved human beings in the US was primarily the domain of white men. Indeed, the objective of Jones-Roberts’ book is ‘to focus on women who owned enslaved people in their own right and, in particular, on the experiences of married slave-owning women…the pecuniary ties formed one of slave-owning women’s primary relations to African American bondage’. Thus, women as slave owners challenges our understanding of the gender identity of women, gender power relations and indeed property rights during this period in US history. She reveals just how far the ownership of enslaved people was a source of economic independence and hence power and status for many white women in the family and society, and the creation of such conditions for women frequently began in early childhood. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Scott F. Aikin and Robert B. Talisse

In ordinary contexts, one is said to be civil when one maintains a soft tone and calm manner in the face of opposition. It is consequently seen as uncivil to be uncompromising, trenchant, and exercised in debate. Civility, it seems, is the requirement that disputants adopt a stance towards one another that minimizes the escalation of hostility. The thought is that disagreement tends to be most productive when enacted in cooler temperatures.

Civility in this ordinary sense of the term is something to be commended. When disputes become needlessly heated, they fly off the rails. And when disputes escalate in this way, the problems and questions over which people divide go unaddressed. Incivility leads either to standstills or to circumstances where one side simply imposes its will on the other. Neither makes for healthy relations.

However, when it comes to political disagreements among democratic citizens, ordinary civility presents a puzzle. Although democracy is commonly associated with its most familiar institutional mechanisms such as elections, voting, campaigns, representative offices, and so on, these draw their justification from the deeper moral ideal that democracy serves. This ideal is self-government among social equals. In other words, democracy is the moral proposal that a relatively stable and just political order is possible in the absence of rulers, lords, and bosses. To be sure, all politics involves the exercise of coercive power; however, in sharing political power as equals, democratic citizens are never simply subjected to force. In a democracy, political power is both constrained by constitutional provisions that protect individual rights and accountable to those over whom it is exercised.

At any rate, that’s the ideal of democracy. It goes without saying that real democracies fall far short. Hence the question arises of whether any existing political order is truly democratic. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

Now that the Emmys are over and we Americans have patted ourselves and a few Brits on the back for outstanding work, it’s time to consider one of the grandest achievements of the past year, a Netflix series from South Korea called Mr. Sunshine, which has, inexplicably, been ignored by media critics in the West.

Now that the Emmys are over and we Americans have patted ourselves and a few Brits on the back for outstanding work, it’s time to consider one of the grandest achievements of the past year, a Netflix series from South Korea called Mr. Sunshine, which has, inexplicably, been ignored by media critics in the West.

Masterpiece Theater meets Gone with the Wind seems a sorry way to try to pigeonhole this epic series and there are those who might want to relegate it to the level of soap opera in costume. Mr. Sunshine is operatic, yes, but there’s not a soap bubble in sight in this multi-faceted, extravagant, scrupulously constructed tale of Korea at the turn of the last century.

I had planned a different essay this time, a critical examination of Nietzsche’s writings on Richard Wagner and was deep into reading and researching for that post when I started Mr. Sunshine. At first, I was able to divide my days between the loquacious, bellicose Mr. N in the morning, and the reticent finesse of a sprawling word-spare historical drama from the Far East at night. As time went on, however, I was lured away from Nietzsche’s late-19th-century twitterstorm, moving deeper into a subtly structured saga set in the Korea of a few years later–its rich, intricate dramaturgy, its attention to detail, its sprawling story, its inspired screenplay. Nietzsche’s infantile trolling of Wagner and counterpunch extolling of Bizet paled against the quiet retributions, political intrigues and slowly unfurling love quadrangle within a roiling cultural and social upheaval on the other side of the globe. Read more »

by Shadab Zeest Hashmi

Oversized photography equipment. Tangled wires.

Oversized photography equipment. Tangled wires.

In a corner, a dusky, crooked mirror.

Ami takes us to the studio for our first passport photos. I am wearing a dress that reminds me of beets for its color and glassy smooth texture. The passport is for a visit to India.

From her purse, ami takes out cash, maybe forty-five rupees for three passport photos and a formal portrait of all three children together.

The rupee coin in India had had Empress Victoria engraved on it for decades by the time my grandparents were born. And around the time my parents were born, the earlier struggle for independence from the British Empire was already becoming the struggle to settle the new nation of Pakistan— the crescent and star newly engraved on the currency. By the year of my own birth, gone was that currency of my parents’ generation, those banknotes with the Bengali script; only Urdu remained— East Pakistan had been split from West Pakistan.

When India was partitioned from Pakistan, my young married aunts had stayed in India while my grandparents migrated with the rest of their children to Dhaka, East Pakistan. It was there my father had attended the American school and prepared for college in the UK, my mother had attended Dhaka University as an exchange student from Lahore, and it was there my parents were engaged.

When another partition was on the horizon, the one between East and West Pakistan, the entire family moved to West Pakistan. In the late sixties, my father returned from London and married my mother in Lahore.

I am negotiating wires and tripods, making my way to the mirror. Read more »

Jillian Berman in Market Watch:

Since at least the Great Recession a decade ago, borrowers, activists and others have been building a case that erasing debt acquired during students college years is a matter of economic justice. More recently, researchers have found that canceling some or all of the nation’s outstanding student debt has the potential to boost gross domestic product, narrow the widening racial wealth gap and liberate millions of Americans from a financial albatross that previous generations never had to contend with.

Since at least the Great Recession a decade ago, borrowers, activists and others have been building a case that erasing debt acquired during students college years is a matter of economic justice. More recently, researchers have found that canceling some or all of the nation’s outstanding student debt has the potential to boost gross domestic product, narrow the widening racial wealth gap and liberate millions of Americans from a financial albatross that previous generations never had to contend with.

Sens. Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders, both vying for the Democratic nomination for president, are proposing to wipe away some or all of the country’s burdensome debt as a key part of their campaigns. They plan to pay for it — and accompanying proposals to make public college tuition-free — by raising taxes on the wealthy. Warren estimates her plan would cost $1.25 trillion over 10 years, and Sanders says his would cost $2.2 trillion.

Critics question whether those proposals would fix the underlying problems in the way Americans pay for college, and also whether student-debt cancellation would entail a giveaway to well-off families.

More here.

Sarah Leonard in The New Republic:

In 1958, sociologist Michael Young wrote a dark satire called The Rise of the Meritocracy. The term “meritocracy” was Young’s own coining, and he chose it to denote a new aristocracy based on expertise and test-taking instead of breeding and titles. In Young’s book, set in 2034, Britain is forced to evolve by international economic competition. The elevation of IQ over birth first serves as a democratizing force championed by socialists, but ultimately results in a rigid caste system. The state uses universal testing to identify and elevate meritocrats, leaving most of England’s citizens poor and demoralized, without even a legitimate grievance, since, after all, who could argue that the wise should not rule? Eventually, a populist movement emerges. The story ends in bloody revolt and the assassination of the fictional author before he can review his page proofs.

In 1958, sociologist Michael Young wrote a dark satire called The Rise of the Meritocracy. The term “meritocracy” was Young’s own coining, and he chose it to denote a new aristocracy based on expertise and test-taking instead of breeding and titles. In Young’s book, set in 2034, Britain is forced to evolve by international economic competition. The elevation of IQ over birth first serves as a democratizing force championed by socialists, but ultimately results in a rigid caste system. The state uses universal testing to identify and elevate meritocrats, leaving most of England’s citizens poor and demoralized, without even a legitimate grievance, since, after all, who could argue that the wise should not rule? Eventually, a populist movement emerges. The story ends in bloody revolt and the assassination of the fictional author before he can review his page proofs.

In 2001, Young would take to The Guardian to declare his disappointment that Tony Blair, alongside politicians in the United States, had adopted the term without irony. The New Labour government now talked of “breaking down the barriers to success” and declared that “the Britain of the elite is over. The new Britain is a meritocracy.” Blair’s Cabinet, like George W. Bush’s and then Obama’s, was packed with graduates of the most elite educational institutions in the world. Young’s vision of IQ testing may have been a little off, but elite education had become the prerequisite for power. “It is good sense to appoint individual people to jobs on their merit,” Young wrote. “It is the opposite when those who are judged to have merit of a particular kind harden into a new social class without room in it for others.”

Sixty years on from Young’s book, a pure product of meritocratic training has emerged to write what he hopes will be the epitaph for his class.

More here.

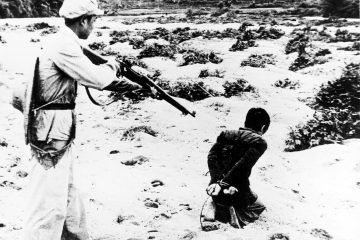

Frank Dikötter in The New Republic:

China today, for any visitor who remembers the country from 20 or 30 years ago, seems hardly recognizable. One of the government’s greatest accomplishments is to have distanced itself so successfully from the Mao era that it seems almost erased. Instead of collective poverty and marching Red Guards, there are skyscrapers, new airports, highways, railway stations, and bullet trains. Yet scratch the glimmering surface and the iron underpinnings of the one-party state become apparent. They have barely changed since 1949, despite all the talk about “reform and opening up.” The legacy of liberation is a country still in chains.

Just what was China liberated from in 1949? It wasn’t the Japanese, defeated four years earlier by the Allies, including the Nationalists and their leader, Chiang Kai-shek. It wasn’t colonialism—all the foreign concessions in the country had been dissolved, some as early as 1929. The Republic of China was a sovereign state and a permanent member of the U.N. Security Council.

Nor was it tyranny. In 1912, when China became Asia’s first republic, it had an electorate of 40 million people, or 10 percent of the population, a level of popular representation not reached by Japan until 1928 and India until 1935. Participatory politics, despite many setbacks, continued to thrive over the following decades. When the National Assembly met in May 1948, upwards of 1,400 delegates from all parts of China adopted a constitution that contained an elaborate bill of rights.

More here.

Richard Johnson in IEEE Spectrum:

Affective computing systems are being developed to recognize, interpret, and process human experiences and emotions. They all rely on extensive human behavioral data, captured by various kinds of hardware and processed by an array of sophisticated machine learning software applications.

Affective computing systems are being developed to recognize, interpret, and process human experiences and emotions. They all rely on extensive human behavioral data, captured by various kinds of hardware and processed by an array of sophisticated machine learning software applications.

AI-based software lies at the heart of each system’s ability to interpret and act on users’ emotional cues. These systems identify and link nuances in behavioral data with the associated emotion.

The most obvious types of hardware for collecting behavior data are cameras and other scanning devices that monitor facial expressions, eye movements, gestures, and postures. This data can be processed to identify subtle micro expressions that a human assessment might struggle to identify consistently.

What’s more, high-end audio equipment records variances and textures in users’ voices. Some insurance companies are experimenting with call voice analytics that can detect if someone is lying to their claim handers.

More here. [Thanks to Brian Whitney.]

Astra Taylor in Lapham’s Quarterly:

Twelve years, or so the scientists told us in 2018, which means now we are down to eleven. That’s how long we have to pull back from the brink of climate catastrophe by constraining global warming to a maximum of 1.5 degrees Celsius. Eleven years to prevent the annihilation of coral reefs, greater melting of the permafrost, and species apocalypse, along with the most dire consequences for human civilization as we know it. Food shortages, forest fires, droughts and monsoons, intensified war and conflict, billions of refugees—we have barely begun to conceive of the range of dystopian futures looming on the horizon.

Twelve years, or so the scientists told us in 2018, which means now we are down to eleven. That’s how long we have to pull back from the brink of climate catastrophe by constraining global warming to a maximum of 1.5 degrees Celsius. Eleven years to prevent the annihilation of coral reefs, greater melting of the permafrost, and species apocalypse, along with the most dire consequences for human civilization as we know it. Food shortages, forest fires, droughts and monsoons, intensified war and conflict, billions of refugees—we have barely begun to conceive of the range of dystopian futures looming on the horizon.

One person who looks squarely and prophetically at the potential ramifications of climate change and insists on a response is Greta Thunberg, the sixteen-year-old Swedish environmentalist who launched a global wave of youth climate strikes. In April 2019 she gave a tour de force address in the British Parliament, invoking not just her peers who were regularly missing class to protest government inaction but those yet to be born. “I speak on behalf of future generations,” Thunberg said. “Many of you appear concerned that we are wasting valuable lesson time, but I assure you we will go back to school the moment you start listening to science and give us a future.”

Thunberg accepts what many influential adults seem unable to face: the inevitability of change. Change is coming, either in the form of adaptation or annihilation; we can respond proactively or reactively to this discomfiting fact. Perhaps she can accept this because she is so young. Eleven years, a little over a decade, is the time for a human infant to become a preteen and for a preteen to become a young adult. For Thunberg, eleven years is more than two-thirds of her life, a veritable expanse that, projected forward, will involve crossing the threshold from adolescence to the first stage of maturity. Yet for a relatively contented middle-aged or elderly adult, eleven years isn’t as substantial—not quite the blink of an eye but a continuation of the present, a deeper dive into one’s golden years. At a certain point, stasis is the goal, to ward off decline. But decline awaits us all—as the economist John Maynard Keynes bluntly put it, “In the long run we are all dead.” Everyone’s time on earth must come to an end. The question is, What do we do with such knowledge?

More here.

Dave Denison in The Baffler:

ONE OF THE GREAT PERVERSITIES in American politics today is that we see Christian leaders taking their cues from Donald Trump, rather than the other way around. And the perfect example of this inversion—the archetype of the Trumpian-Christian—is Jerry Falwell Jr., the president of Liberty University in Lynchburg, Virginia. Unlike his late father, Jerry Falwell Sr., who founded Liberty University in 1971 and the Moral Majority in 1979, the junior Falwell is not a reverend. His background is in real estate development. But because of his famous name and his perch at the top of a large and prominent Baptist-founded college, his support for Donald Trump in the 2016 Republican primaries was seen as a key turning point in the campaign. It came at a time when Texas Senator Ted Cruz had been expecting Falwell’s endorsement and when Cruz seemed to be emerging as the consensus candidate for conservative Christians. Falwell, of course, has been steadfast in his devotion to the president ever since. Trump accepted an invitation to speak at Liberty’s commencement ceremony in May of 2017. And the intervening months have made one thing clear: mingling with Christians makes no impression whatsoever on Trump. But Trump seems to have become a role model for his Christian admirers. You can see the dynamic play out in an uncanny way in Falwell’s recent life and times.

ONE OF THE GREAT PERVERSITIES in American politics today is that we see Christian leaders taking their cues from Donald Trump, rather than the other way around. And the perfect example of this inversion—the archetype of the Trumpian-Christian—is Jerry Falwell Jr., the president of Liberty University in Lynchburg, Virginia. Unlike his late father, Jerry Falwell Sr., who founded Liberty University in 1971 and the Moral Majority in 1979, the junior Falwell is not a reverend. His background is in real estate development. But because of his famous name and his perch at the top of a large and prominent Baptist-founded college, his support for Donald Trump in the 2016 Republican primaries was seen as a key turning point in the campaign. It came at a time when Texas Senator Ted Cruz had been expecting Falwell’s endorsement and when Cruz seemed to be emerging as the consensus candidate for conservative Christians. Falwell, of course, has been steadfast in his devotion to the president ever since. Trump accepted an invitation to speak at Liberty’s commencement ceremony in May of 2017. And the intervening months have made one thing clear: mingling with Christians makes no impression whatsoever on Trump. But Trump seems to have become a role model for his Christian admirers. You can see the dynamic play out in an uncanny way in Falwell’s recent life and times.

These times have lately brought some unusual tribulations. The roots of the current troubles go back to 2012, when Falwell and his wife Becki met a “pool boy” at the Fontainebleau Hotel in Florida. They struck up some sort of relationship with him. They decided to back him in a real estate investment involving a “gay-friendly” Miami hostel, which also involved their son Trey, who was then twenty-three. Eventually there was a lawsuit over the financing of the hostel. As several news outlets later reported, there were supposedly racy photos of Becki Falwell circulating that may have been used as leverage in the legal battles. (Falwell has denied the existence of compromising photos “of me,” but in June reporters at the Miami Herald said they had seen three photographs, adding: “They are images not of Falwell, but of his wife in various stages of undress.”)

More here.

Your body, hard vowels

In a soft dress, is still.

What you can’t know

is that after you died

All the black poets

In New York City

Took a deep breath,

And breathed you out;

Dark corners of small clubs,

The silence you left twitching

On the floors of the gigs

You turned your back on,

The balled-up fists of notes

Flung, angry from a keyboard.

You won’t be able to hear us

Try to etch what rose

Off your eyes, from your throat.

Out you bleed, not as sweet, or sweaty,

Through our dark fingertips.

We drum rest

We drum thank you

We drum stay.

by Cornelius Eady

from English Poets.com

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Nina Simone, Mississippi God Damn