Month: October 2019

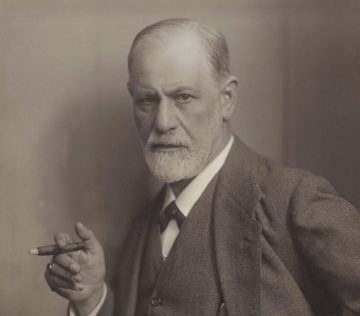

Virtual Roundtable on “The Ego and the Id”

Elizabeth Lunbeck (and others) at Public Books:

It would be hard to overestimate the significance of Freud’s The Ego and the Id for psychoanalytic theory and practice. This landmark essay has also enjoyed a robust extra-analytic life, giving the rest of us both a useful terminology and a readily apprehended model of the mind’s workings. The ego, id, and superego (the last two terms made their debut in The Ego and the Id) are now inescapably part of popular culture and learned discourse, political commentary and everyday talk.

It would be hard to overestimate the significance of Freud’s The Ego and the Id for psychoanalytic theory and practice. This landmark essay has also enjoyed a robust extra-analytic life, giving the rest of us both a useful terminology and a readily apprehended model of the mind’s workings. The ego, id, and superego (the last two terms made their debut in The Ego and the Id) are now inescapably part of popular culture and learned discourse, political commentary and everyday talk.

Type “id ego superego” into a Google search box and you’re likely to be directed to sites offering to explain the terms “for dummies”—a measure of the terms’ ubiquity if not intelligibility. You might also come upon images of The Simpsons: Homer representing the id (motivated by pleasure, characterized by unbridled desire), Marge the ego (controlled, beholden to reality), and Lisa the superego (the family’s dour conscience), all of which need little explanation, so intuitively on target do they seem.

more here.

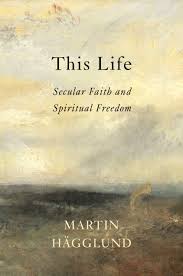

Heaven, Atheism and What Gives Life Meaning

Oliver Burkeman at The Guardian:

Years ago, the magazine US Catholic ran a headline that had the air of being written by a devout believer who had just had an appalling realisation: “Heaven: Will It Be Boring?” If he believed in heaven, the Swedish philosopher Martin Hägglund would answer with an unequivocal yes. And not merely boring: utterly devoid of meaning. “If I believed that my life would last forever,” he writes, “I could never take my life to be at stake.” The question of how to use our precious time wouldn’t arise, because time wouldn’t be precious. Faced with any decision about whether to do something potentially meaningful with any given hour or day – to nurture a relationship, create a work of art, savour a natural scene – the answer would always be: who cares? After all, there’s always tomorrow, and the next day, and the next.

Years ago, the magazine US Catholic ran a headline that had the air of being written by a devout believer who had just had an appalling realisation: “Heaven: Will It Be Boring?” If he believed in heaven, the Swedish philosopher Martin Hägglund would answer with an unequivocal yes. And not merely boring: utterly devoid of meaning. “If I believed that my life would last forever,” he writes, “I could never take my life to be at stake.” The question of how to use our precious time wouldn’t arise, because time wouldn’t be precious. Faced with any decision about whether to do something potentially meaningful with any given hour or day – to nurture a relationship, create a work of art, savour a natural scene – the answer would always be: who cares? After all, there’s always tomorrow, and the next day, and the next.

I sometimes feel oppressed by my seemingly infinite to-do list; but the truth is that having infinite time in which to tackle it would be inconceivably worse. The question at issue here isn’t whether heaven exists.

more here.

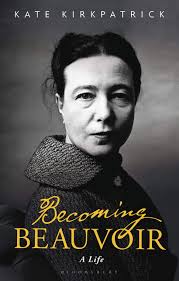

Becoming Beauvoir: A Life

Sarah Ditum at Literary Review:

In Kirkpatrick’s work, Sartre appears far more in need of Beauvoir than Beauvoir is of him. In his later life in particular, it is hard to see him as anything other than pathetic: ruined by alcohol and amphetamines, throwing himself down the intellectual dead-end of Maoism, still skirt-chasing even after several strokes. Much of what is considered to be Sartre’s unique contribution to philosophy and ethics turns out – on consultation of Beauvoir’s letters, diaries and published work – to have started with her.

In Kirkpatrick’s work, Sartre appears far more in need of Beauvoir than Beauvoir is of him. In his later life in particular, it is hard to see him as anything other than pathetic: ruined by alcohol and amphetamines, throwing himself down the intellectual dead-end of Maoism, still skirt-chasing even after several strokes. Much of what is considered to be Sartre’s unique contribution to philosophy and ethics turns out – on consultation of Beauvoir’s letters, diaries and published work – to have started with her.

That goes for the ‘pact’ too. Before the two had discussed such a thing, Beauvoir ‘came to the conclusion that she would love multiple men in the ways she thought them loveable’, writes Kirkpatrick. When the two first met, as students in the late 1920s, Beauvoir may already have had a lover. The record is hazy, understandably so given the censoriousness shown towards unmarried, sexually active women in the early 20th century.

more here.

The Human Brain: Blessing and Curse

Bob Grant in The Scientist:

The most exciting thing about science is that it can ferry humanity into the unknown. The scientific method, as a mode of observation piloted by humans for generations, has probed outer space, the depths of the oceans, and the inner reaches of cells, molecules, and atoms—our amazing brains at the helm. Never satisfied, the three-pound, skull-encased lump of flesh strains to know more, discover more, solve more. And the universe obliges. Unimaginably vast swaths of space lie unexplored; most of the ocean floor remains a mystery; and new insights into the functioning of cells and the nature of subatomic matter emerge on an almost daily basis.

The most exciting thing about science is that it can ferry humanity into the unknown. The scientific method, as a mode of observation piloted by humans for generations, has probed outer space, the depths of the oceans, and the inner reaches of cells, molecules, and atoms—our amazing brains at the helm. Never satisfied, the three-pound, skull-encased lump of flesh strains to know more, discover more, solve more. And the universe obliges. Unimaginably vast swaths of space lie unexplored; most of the ocean floor remains a mystery; and new insights into the functioning of cells and the nature of subatomic matter emerge on an almost daily basis.

This almost unfathomable potential for discovery and innovation always rockets to the fore of my own three-pound fleshlump when it comes time to edit our annual issue on neuroscience. Most scientists and science enthusiasts I’ve met are intellectually inflamed by the fact that there is so much out there (and in here) that we don’t know—a passion that transcends disciplines. And is there any mystery more fascinating than the functioning of the human brain itself? After all, we carry our brains around with us every day and use them to ferret out the patterns and meanings that throng around us. Neuroscientists, even more than the rest of us, use theirs to think about thinking.

Yet, after millennia of intimate interactions with our own brains and decades of formal study of the organ, “how the brain works was and still is a complete mystery,” in the words of Albert Einstein College of Medicine neuroscientist Kamran Khodakhah, this month’s profilee. How in the name of Ramón y Cajal can cells, amassed in tangled networks and swapping ions across their membranes to propagate waves of electrical potential, result in a thought? How does this sequence of physical events form moving pictures, symphonies, emotions, and inspiration? It truly boggles . . . well, the brain.

More here.

Saturday Poem

Unholy Sonnets

1.

Dear God, Our Heavenly Father, Gracious Lord,

Mother Love and Maker, Light Divine,

Atomic Fingertip, Cosmic Design,

First Letter of the Alphabet, Last Word,

Mutual Satisfaction, Cash Award,

Auditor Who Approves Our Bottom Line,

Examiner Who Says That We Are Fine,

Oasis That All Sands Are Running Toward.

I can say almost anything about you,

O Big Idea, and with each epithet,

Create new reasons to believe or doubt you,

Black Hole, White Hole, Presidential Jet.

But what’s the anything I must leave out? You

Solve nothing but the problems that I set.

by Mark Jarman

from Unholy Sonnets

Story Line Press, 2003

Gandhi’s Enemies

Faisal Devji in India Today:

If Gandhi lives today it is because of his enemies, who seem unable to let go of his memory. The Mahatma’s followers have turned him into a saint whose teachings can safely be ignored-as the words of a superior being to be admired from afar.

If Gandhi lives today it is because of his enemies, who seem unable to let go of his memory. The Mahatma’s followers have turned him into a saint whose teachings can safely be ignored-as the words of a superior being to be admired from afar.

Given the ritualistic respect offered to him in India and received with public indifference, it is puzzling why Gandhi remains such a living figure for his critics. Perhaps they are the only ones who still feel betrayed by his loss of sainthood. This betrayal is renewed in every generation, as scholars and activists discover yet another of the Mahatma’s failings.

In the wake of second-wave feminism, the Mahatma, during the 1980s, was excoriated for his views about women. The criticism was based on anecdotes about Gandhi’s treatment of his wife Kasturbai and his experiments with celibacy that entailed sleeping naked with young women.

But these women’s voices are strangely silenced. Manubehn, who participated in Gandhi’s experiments, has left a diary that no critic has thought to read. While he was sometimes harsh to his intimates, it was also from Gandhi’s circle that many women entered public life-Anasuya Sarabhai, Mridula Sarabhai, Amrit Kaur, Sarojini Naidu and Sushila Nayyar.

In the 1990s, when the Mandal Commission revived caste struggle in India, Gandhi’s caste prejudice came into focus.

More here.

Elusive protein and key to many tropical diseases found after decades of searching

Bradley Van Paridon in Chemistry World:

A chance decision to attend a lecture led to the discovery of an elusive protein and promising drug target for parasites causing some of the world’s most notorious neglected tropical diseases – Chagas disease, sleeping sickness and leishmaniasis. As this protein had been so slippery and hard to track down some had doubted that it even existed in these parasites at all.

A chance decision to attend a lecture led to the discovery of an elusive protein and promising drug target for parasites causing some of the world’s most notorious neglected tropical diseases – Chagas disease, sleeping sickness and leishmaniasis. As this protein had been so slippery and hard to track down some had doubted that it even existed in these parasites at all.

Trypanosomes are a group of protozoan parasites transmitted by insect bites that cause sickness, morbidity and death in humans and livestock in developing countries. They are responsible for sickening millions of people every year and cause the deaths of tens of thousands of those infected, but the diseases these parasites cause do not receive the attention others do as they mostly affect poorer people in the Global South.

For decades trypanosome researchers have searched for a protein called Pex3 within the genomes of trypanosomes.

More here.

The endurance of the liberal imagination

James Duesterberg in The Point:

“In the United States at this time,” Lionel Trilling wrote in 1949, “liberalism is not only the dominant but even the sole intellectual tradition.” These words are strange to read today. One cannot imagine someone writing them now and, in retrospect, they suggest a dangerous hubris. And yet it is not clear that, applied either to Trilling’s time or to ours, they are wrong.

“In the United States at this time,” Lionel Trilling wrote in 1949, “liberalism is not only the dominant but even the sole intellectual tradition.” These words are strange to read today. One cannot imagine someone writing them now and, in retrospect, they suggest a dangerous hubris. And yet it is not clear that, applied either to Trilling’s time or to ours, they are wrong.

Since the global political unraveling in 2016, liberalism has lost its voice. From the “basket of deplorables” to the “#resistance” pins to the eat-pray-love liberalism of “a thousand small sanities,” public defenses of the West’s regnant political ideology ring hollow and desperate. Read the Times or the Post, listen to politicians, sit for a second and catch the mood in the airport: the absence is in the air, not just in our language. Max Weber called twentieth-century governance the “slow boring of hard boards”: they have been bored, and so are we.

To literary critics and political theorists—those whose job it is to front-run the zeitgeist—liberalism now seems not so much an opponent to battle as a corpse to put to rest. It is something to be, at most, anatomized, if not simply buried and forgotten.

More here.

Sabine Hossenfelder: The Trouble with the Many Worlds Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics

Elgar’s Dream of Gerontius

Sudip Bose at The American Scholar:

In the annals of disastrous musical premieres, that of Edward Elgar’s Dream of Gerontius, which took place on this date in 1900, wasn’t a complete fiasco in the manner of, say, Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring or Bruckner’s Third Symphony. It did not, however, go well—not by any measure. So poor was the performance, so distant the musicians’ execution from Elgar’s most vivid and hopeful imagining, that the experience left the composer despondent. A devout Catholic, he even briefly lost his faith.

In the annals of disastrous musical premieres, that of Edward Elgar’s Dream of Gerontius, which took place on this date in 1900, wasn’t a complete fiasco in the manner of, say, Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring or Bruckner’s Third Symphony. It did not, however, go well—not by any measure. So poor was the performance, so distant the musicians’ execution from Elgar’s most vivid and hopeful imagining, that the experience left the composer despondent. A devout Catholic, he even briefly lost his faith.

Elgar first encountered John Henry Newman’s sprawling poem “The Dream of Gerontius” in 1889, the year he got married. The wedding ceremony was held in St. George’s Church in the English city of Worcester, where Elgar, like his father, had been the organist. The priest at St. George’s marked the occasion by presenting him with a copy of the poem, which Newman had published in 1865—two decades after his conversion from Anglicanism to Roman Catholicism and 14 years before he would become a cardinal.

more here.

How Edward Snowden Found His Conscience

Jacob Silverman at The Baffler:

A series of discoveries, each disturbing in turn, leads to Snowden’s eventual decision to stockpile documents, smuggle them out of the Hawaiian bunker where he works for the NSA, and flee with them to Hong Kong, where he would meet the documentary filmmaker Laura Poitras and journalists Glenn Greenwald and Ewen MacAskill. One such discovery was that of Stellar Wind, a bulk surveillance program that previous NSA whistleblowers had tried to warn lawmakers about. Through these and other programs, through the building of an unprecedentedly massive data center in Utah, through the boasts of a CIA technologist who talks about collecting and computing on all information generated in the world, Snowden begins to understand that “surveillance wasn’t something occasional and directed in legally justified circumstances, but a constant and indiscriminate presence . . . a memory that is sleepless and permanent.” The machine reaches everywhere, collapsing space, time, and memory into a single archive. “I now understood that I was totally transparent to my government,” he acknowledges with the finality of someone accepting a cancer diagnosis. Even the promises of free speech become illusory under the surveillance regime, as “self-expression now required such strong self-protection as to obviate its liberties and nullify its pleasures.”

A series of discoveries, each disturbing in turn, leads to Snowden’s eventual decision to stockpile documents, smuggle them out of the Hawaiian bunker where he works for the NSA, and flee with them to Hong Kong, where he would meet the documentary filmmaker Laura Poitras and journalists Glenn Greenwald and Ewen MacAskill. One such discovery was that of Stellar Wind, a bulk surveillance program that previous NSA whistleblowers had tried to warn lawmakers about. Through these and other programs, through the building of an unprecedentedly massive data center in Utah, through the boasts of a CIA technologist who talks about collecting and computing on all information generated in the world, Snowden begins to understand that “surveillance wasn’t something occasional and directed in legally justified circumstances, but a constant and indiscriminate presence . . . a memory that is sleepless and permanent.” The machine reaches everywhere, collapsing space, time, and memory into a single archive. “I now understood that I was totally transparent to my government,” he acknowledges with the finality of someone accepting a cancer diagnosis. Even the promises of free speech become illusory under the surveillance regime, as “self-expression now required such strong self-protection as to obviate its liberties and nullify its pleasures.”

more here.

Beautiful Terrible Vilna

Daniel Mendelsohn at the NYRB:

Stendhal didn’t like Vilna, either.

Stendhal didn’t like Vilna, either.

In Book Five of his History of Painting in Italy, the author describes Vilna as the site of his own personal trauma, a bad moment that had occurred on June 6, 1812, as he stood, he says, on the banks of the Neman, watching the Grande Armée pass into Russia. This was at the triumphant beginning of Napoleon’s Russian campaign, when there was no reason yet for despair. And yet, he wrote in this book—the manuscript of which, as it happens, he gathered together for the first time while he was in Lithuania, having brought it from Paris and worked on it steadily all the time he was serving in the Armée—he felt a certain sadness pass over him as he watched this innumerable army cross the river, one composed of so many peoples, and which was to suffer the most memorable defeat history can tell of. The glum future that I perceived in the depths of Russia’s endless plains, together with our general’s erratic genius, filled me with doubt. Wearied by these pointless conjectures, I turned my mind to positive thoughts, that faithful stay in all manner of fortune.

more here.

Leapfrog to speciation boosted by mother’s influence

Machteld Verzijden in Nature:

Females of O. pumilio lay eggs on the ground, on a leaf covered by other foliage, where they are fertilized by the male. During the following week, the male ensures that the eggs stay wet, and after the eggs have hatched, the female takes over the parental care. She carries each tadpole on her back (Fig. 1) to a water-filled bromeliad plant, and then returns to feed the tadpole with her unfertilized eggs until it is sexually mature. The authors studied three colour types of O. pumilio, and carried out laboratory experiments involving three set-ups: tadpoles were raised by their biological parents, which were both the same colour; they were raised by their parents, which were of different colours; or they were raised by foster frogs that were not the same colour as the tadpoles’ parents. For all three scenarios, when the female tadpoles became adults, female offspring preferred to mate with males of the same colour as the mother that had reared them.

Females of O. pumilio lay eggs on the ground, on a leaf covered by other foliage, where they are fertilized by the male. During the following week, the male ensures that the eggs stay wet, and after the eggs have hatched, the female takes over the parental care. She carries each tadpole on her back (Fig. 1) to a water-filled bromeliad plant, and then returns to feed the tadpole with her unfertilized eggs until it is sexually mature. The authors studied three colour types of O. pumilio, and carried out laboratory experiments involving three set-ups: tadpoles were raised by their biological parents, which were both the same colour; they were raised by their parents, which were of different colours; or they were raised by foster frogs that were not the same colour as the tadpoles’ parents. For all three scenarios, when the female tadpoles became adults, female offspring preferred to mate with males of the same colour as the mother that had reared them.

Yang and colleagues demonstrated that male offspring had an imprinted behaviour, too. These frogs biased their territorial aggression towards males of the same colour as the mother that had reared them.

More here.

Gaugin and Van Gogh’s social networks: two of art’s supposed “great loners” were deeply social painters

Michael Prodger in New Humanist:

For nine weeks in late 1888, two of art’s great loners lived together. The home and studio Paul Gauguin and Vincent Van Gogh shared was the small and unassuming “Yellow House”, just outside the northern city gate of Arles in the south of France. There was an imbalance to the arrangement. Van Gogh thought the older man, a painter he adulated, had arrived from Paris to help him realise his dream of creating an artists’ haven, a “studio in the south”; Gauguin was in fact paid by Theo van Gogh, a successful art dealer and the white sheep of the family, to act as painter-chaperone to his troubled brother.

For nine weeks in late 1888, two of art’s great loners lived together. The home and studio Paul Gauguin and Vincent Van Gogh shared was the small and unassuming “Yellow House”, just outside the northern city gate of Arles in the south of France. There was an imbalance to the arrangement. Van Gogh thought the older man, a painter he adulated, had arrived from Paris to help him realise his dream of creating an artists’ haven, a “studio in the south”; Gauguin was in fact paid by Theo van Gogh, a successful art dealer and the white sheep of the family, to act as painter-chaperone to his troubled brother.

Initially, the two artists revelled in the stimulation of close companionship: they painted together, drank together, discussed art together, and visited a local brothel together. However, companionability soon turned to conflict due to what Gauguin described as “incompatibility of temperament” and Vincent’s mental state assuming a dangerous edge. The day Van Gogh was hospitalised following the most celebrated act of self-mutilation in art, Gauguin left for Paris and eventually Tahiti and the Marquesas Islands. The two men never saw each other again.

The painters have been viewed traditionally as men ill at ease in company and itchy with the constraints of society. In pursuit of personal freedom Gauguin left his Danish wife and five children and later France itself. Van Gogh meanwhile was the perpetual outsider, viewed with suspicion in his native Brabant in Holland; in the Borinage in Belgium, where he had a brief spell as a preacher; and in Arles, where his neighbours signed a petition to have the disturbed and disturbing painter removed from the city.

More here.

Friday Poem

Forgiveness

My heart was heavy, for its trust had been

Abused, its kindness answered with foul wrong;

So, turning gloomily from my fellow-men,

One summer Sabbath day I strolled among

The green mounds of the village burial-place;

Where, pondering how all human love and hate

Find one sad level; and how, soon or late,

Wronged and wrongdoer, each with meekened face,

And cold hands folded over a still heart,

Pass the green threshold of our common grave,

Whither all footsteps tend, whence none depart,

Awed for myself, and pitying my race,

Our common sorrow, like a mighty wave,

Swept all my pride away, and trembling I forgave!

The Delusion and Danger of Infinite Economic Growth

Christopher F. Jones in The New Republic:

One of the reasons nations fail to address climate change is the belief that we can have infinite economic growth independent of ecosystem sustainability. Extreme weather events, melting arctic ice, and species extinction expose the lie that growth can forever be prioritized over planetary boundaries.

One of the reasons nations fail to address climate change is the belief that we can have infinite economic growth independent of ecosystem sustainability. Extreme weather events, melting arctic ice, and species extinction expose the lie that growth can forever be prioritized over planetary boundaries.

It wasn’t always this way. The fairytale of infinite growth—which so many today accept as unquestioned fact—is relatively recent. Economists have only begun to model never-ending growth over the last 75 years. Before that, they had ignored the topic for a century. And before that, they had believed in limits. If more people saw the idea of infinite growth as a departure from the history of economics rather than a timeless law of nature, perhaps they’d be readier to reimagine the links between the environment and the economy.

In 1950, the economics profession had surprisingly little to say about growth. That year, the American Economic Association (AEA) asked Moses Abramovitz to write a state-of-the-field essay on economic growth. He quickly discovered a problem: There was no field to review.

More here.

Are Neanderthals the same species as us?

Chris Stringer at the website of the British Natural History Museum:

The biological species concept states that species are reproductively isolated entities – that is, they breed within themselves but not with other species. Thus all living Homo sapiens have the potential to breed with each other, but could not successfully interbreed with gorillas or chimpanzees, our closest living relatives.

The biological species concept states that species are reproductively isolated entities – that is, they breed within themselves but not with other species. Thus all living Homo sapiens have the potential to breed with each other, but could not successfully interbreed with gorillas or chimpanzees, our closest living relatives.

On this basis, ‘species’ that interbreed with each other cannot actually be distinct species.

Critics who disagree that H. neanderthalensis and H. sapiens are two separate species can now cite supporting evidence from recent genetic research. This indicates that the two interbred with each other when they met outside Africa about 55,000 years ago. As a result, everyone today whose ancestors lived outside Africa at that time has inherited a small but significant amount of Neanderthal DNA, which makes up about 2% of their genomes.

In the face of this seemingly decisive evidence, why do I cling to my belief that Neanderthals and Homo sapiens are distinct species?

More here.

Fidel Castro’s secret love affair with NYC

Tony Perrottet at the BBC:

On a recent sun-drenched afternoon, I was wandering the leafy blocks of West 82nd Street near Central Park, when I came to number 155, a stately Victorian brownstone with a carved stone stoop. Not so different from 1,000 other addresses on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, I thought – except that this is where the young Fidel Castro, a then-unknown 22-year-old Cuban law graduate, stayed on his honeymoon in 1948.

On a recent sun-drenched afternoon, I was wandering the leafy blocks of West 82nd Street near Central Park, when I came to number 155, a stately Victorian brownstone with a carved stone stoop. Not so different from 1,000 other addresses on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, I thought – except that this is where the young Fidel Castro, a then-unknown 22-year-old Cuban law graduate, stayed on his honeymoon in 1948.

Castro had been a vocal student leader back in Havana, but there was nothing in 1948 to indicate that he would soon lead a revolution on his home island and become one of the most famous and divisive figures of the 20th Century, thrusting Cuba into a bitter Cold War feud with the United States that continues to this day.

It was Castro’s first visit to the US and he fell in love with New York immediately. He was fascinated by the subway, the skyscrapers, the size of the steaks, and the fact that, despite the rabid anti-Communism of the US during the Cold War, he could find Karl Marx’s anti-capitalist jeremiad, Das Kapital, in any bookstore.

More here.