Nick Burns at The Hedgehog Review:

Is modern-day philanthropy a disease in the democratic body politic? Rob Reich, a professor of political science at Stanford University (not to be confused with former secretary of labor Robert Reich), believes that it is. And Reich is not alone. Near-universal outrage over the recent college admissions scandal has left two black eyes on American philanthropy: one for the role of Rick Singer’s fraudulent 501(c)(3) organization, Key Worldwide Foundation, in bribing several elite universities to accept children of privilege; the other for the universities’ susceptibility to such schemes. Reich’s book went to press well before the scandal broke, but it is hard to imagine a better indication of his central claim: that philanthropy amplifies the power of the few at the expense of the many.

Is modern-day philanthropy a disease in the democratic body politic? Rob Reich, a professor of political science at Stanford University (not to be confused with former secretary of labor Robert Reich), believes that it is. And Reich is not alone. Near-universal outrage over the recent college admissions scandal has left two black eyes on American philanthropy: one for the role of Rick Singer’s fraudulent 501(c)(3) organization, Key Worldwide Foundation, in bribing several elite universities to accept children of privilege; the other for the universities’ susceptibility to such schemes. Reich’s book went to press well before the scandal broke, but it is hard to imagine a better indication of his central claim: that philanthropy amplifies the power of the few at the expense of the many.

Philanthropy, Reich reasons, is necessarily “a form or exercise of power.” Under the current regime, it is an undemocratic sort of power: Bill Gates’s donations to public schools, for example, give him a measure of curricular control that cannot be wrested away at the ballot box. Though Reich favors greater government oversight and a freer hand for representative bodies to regulate charities’ operations, he goes a step further by arguing for the abolition of American philanthropy’s legal mainstay: the tax deduction.

more here.

The lectures reveal the various themes and preoccupations in Foucault’s work in the 1970s and 80s; they also help to contextualize many of the changes in his thought. Still, it is difficult to characterize Foucault’s work. He often denied that he was a theorist, by which he meant someone who works within an overarching system. Describing himself as an experimenter, Foucault frequently underscored the tentative and fragmentary nature of his research. His work is also anti-systematic in the sense that it explores the logic of specific mechanisms, technologies and strategies of power. This exploration requires that close attention be paid to historical conditions whose singularity defies subsumption under a universal history. But Foucault’s antipathy towards systematic thought also meant that he enthusiastically pursued new directions in his research (his later study of care of the self in ancient Greece and Hellenistic Rome is a case in point), and he readily acknowledged the disparities between his earlier and later work.

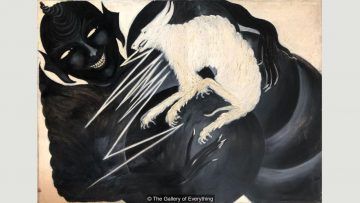

The lectures reveal the various themes and preoccupations in Foucault’s work in the 1970s and 80s; they also help to contextualize many of the changes in his thought. Still, it is difficult to characterize Foucault’s work. He often denied that he was a theorist, by which he meant someone who works within an overarching system. Describing himself as an experimenter, Foucault frequently underscored the tentative and fragmentary nature of his research. His work is also anti-systematic in the sense that it explores the logic of specific mechanisms, technologies and strategies of power. This exploration requires that close attention be paid to historical conditions whose singularity defies subsumption under a universal history. But Foucault’s antipathy towards systematic thought also meant that he enthusiastically pursued new directions in his research (his later study of care of the self in ancient Greece and Hellenistic Rome is a case in point), and he readily acknowledged the disparities between his earlier and later work. Great sculptors are rare and strange. In Western art, whole eras have gone by without one, and one at a time is how these artists come. I mean sculptors who epitomize their epochs in three dimensions that acquire the fourth, of time, in the course of our fascination. There’s always something disruptive—uncalled for—about them. Their effects partake in a variant of the sublime that I experience as, roughly, beauty combined with something unpleasant. I think of the marble carvings of Gian Lorenzo Bernini in Rome: the Baroque done to everlasting death. A feeling of excess in both form and fantasy may be disagreeable—there’s so much going on as Daphne morphs into a tree to escape Apollo, or a delighted seraph stabs an ecstatic St. Teresa in the heart with an arrow. But try to detect an extraneous curlicue or an unpersuasive gesture. Everything works! Move around. A newly magnificent unity coalesces at each step. You’re knocked sideways out of comparisons to other art in any medium or genre. Four centuries of intervening history evaporate. Being present in the body is crucial to beholding Bernini’s incarnations. Painting can’t compete with this total engagement. It doesn’t need to, because great sculpture is so difficult and, in each instance, so particular and even bizarre.

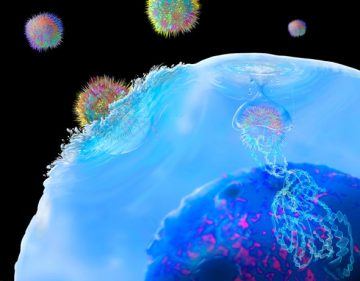

Great sculptors are rare and strange. In Western art, whole eras have gone by without one, and one at a time is how these artists come. I mean sculptors who epitomize their epochs in three dimensions that acquire the fourth, of time, in the course of our fascination. There’s always something disruptive—uncalled for—about them. Their effects partake in a variant of the sublime that I experience as, roughly, beauty combined with something unpleasant. I think of the marble carvings of Gian Lorenzo Bernini in Rome: the Baroque done to everlasting death. A feeling of excess in both form and fantasy may be disagreeable—there’s so much going on as Daphne morphs into a tree to escape Apollo, or a delighted seraph stabs an ecstatic St. Teresa in the heart with an arrow. But try to detect an extraneous curlicue or an unpersuasive gesture. Everything works! Move around. A newly magnificent unity coalesces at each step. You’re knocked sideways out of comparisons to other art in any medium or genre. Four centuries of intervening history evaporate. Being present in the body is crucial to beholding Bernini’s incarnations. Painting can’t compete with this total engagement. It doesn’t need to, because great sculpture is so difficult and, in each instance, so particular and even bizarre. In one type of cancer immunotherapy, immune cells called T cells are removed from the body and engineered to target cells that are only found in cancers. The engineered cells, called chimeric antigen receptor T cells (CAR-Ts), have proved exceedingly effective against some types of blood cancers, particularly acute lymphocytic leukemia. Scientists have now started engineering T cells to attack other disease-related cells.

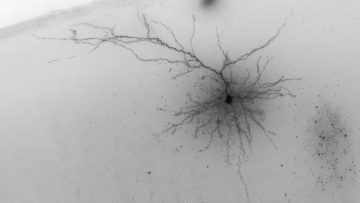

In one type of cancer immunotherapy, immune cells called T cells are removed from the body and engineered to target cells that are only found in cancers. The engineered cells, called chimeric antigen receptor T cells (CAR-Ts), have proved exceedingly effective against some types of blood cancers, particularly acute lymphocytic leukemia. Scientists have now started engineering T cells to attack other disease-related cells. Sugar isn’t just for sweets. Inside cells, sugars attached to proteins and fats help molecules recognize one another—and let cells communicate. Now, for the first time, researchers report that sugars also appear to bind to some RNA molecules, the cellular workhorses that do everything from translating DNA into proteins to catalyzing chemical reactions. It’s unclear just what these sugar-coated RNAs do. But if the result holds up, it suggests vast new roles for RNA.

Sugar isn’t just for sweets. Inside cells, sugars attached to proteins and fats help molecules recognize one another—and let cells communicate. Now, for the first time, researchers report that sugars also appear to bind to some RNA molecules, the cellular workhorses that do everything from translating DNA into proteins to catalyzing chemical reactions. It’s unclear just what these sugar-coated RNAs do. But if the result holds up, it suggests vast new roles for RNA. Imagine you’re driving a trolley car. Suddenly the brakes fail, and on the track ahead of you are five workers you’ll run over. Now, you can steer onto another track, but on that track is one person who you will kill instead of the five: It’s the difference between unintentionally killing five people versus intentionally killing one.

Imagine you’re driving a trolley car. Suddenly the brakes fail, and on the track ahead of you are five workers you’ll run over. Now, you can steer onto another track, but on that track is one person who you will kill instead of the five: It’s the difference between unintentionally killing five people versus intentionally killing one.  Anne Carson 4/1

Anne Carson 4/1 The upshot is that a subtle and mostly forgotten centuries-old choice in mathematical thinking has sent economics hurtling down a strange path. Only now are we beginning to learn how it might have been otherwise – and how a more realistic approach could help re-align economic orthodoxy with reality, to the benefit of all.

The upshot is that a subtle and mostly forgotten centuries-old choice in mathematical thinking has sent economics hurtling down a strange path. Only now are we beginning to learn how it might have been otherwise – and how a more realistic approach could help re-align economic orthodoxy with reality, to the benefit of all. In Rolling Stone, Greil Marcus

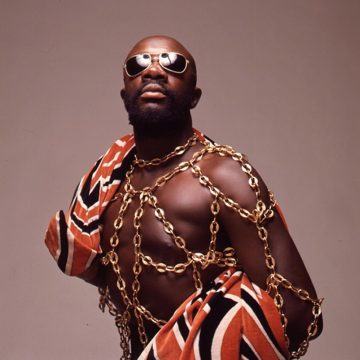

In Rolling Stone, Greil Marcus  The meaning of Hayes’s music was similarly complex. But his seizure of musical space—literalized in the LP jacket for “Black Moses,” which unfolded to reveal a full-length portrait of Hayes in a robe, his arms outstretched—made a political statement at a time when black people were being made to feel acutely unwelcome in the public sphere: patrolled by police in their own neighborhoods, maimed and killed for being “in the wrong place at the wrong time.” Hayes took up time and space as if it were owed him, and listeners responded. “Hot Buttered Soul,” despite being what the critic Phyl Garland called “probably the strangest record hit of the year,” became the first Stax LP to go gold. It sold a million records to black consumers alone.

The meaning of Hayes’s music was similarly complex. But his seizure of musical space—literalized in the LP jacket for “Black Moses,” which unfolded to reveal a full-length portrait of Hayes in a robe, his arms outstretched—made a political statement at a time when black people were being made to feel acutely unwelcome in the public sphere: patrolled by police in their own neighborhoods, maimed and killed for being “in the wrong place at the wrong time.” Hayes took up time and space as if it were owed him, and listeners responded. “Hot Buttered Soul,” despite being what the critic Phyl Garland called “probably the strangest record hit of the year,” became the first Stax LP to go gold. It sold a million records to black consumers alone. Lab mice endure a lot for science, but there’s often one (temporary) compensation: near-miraculous recovery from diseases that kill people. Unfortunately, experimental drugs that have cured millions of mice with Alzheimer’s disease or schizophrenia or glioblastoma have cured zero people — reflecting the sad fact that, for many brain disorders, mice are pretty lousy models of how humans will respond to a drug. Scientists have now discovered a key reason for that mouse-human disconnect, they

Lab mice endure a lot for science, but there’s often one (temporary) compensation: near-miraculous recovery from diseases that kill people. Unfortunately, experimental drugs that have cured millions of mice with Alzheimer’s disease or schizophrenia or glioblastoma have cured zero people — reflecting the sad fact that, for many brain disorders, mice are pretty lousy models of how humans will respond to a drug. Scientists have now discovered a key reason for that mouse-human disconnect, they  Every age invents the language that it needs. Posterity will determine what it says about our own era that we have felt compelled to craft such words and phrases as ‘defriended’, ‘photobomb’, ‘flash mob’, ‘happy slapping’ and ‘selfie’. When our forebears in the 1850s found themselves at a loss for a term to describe the new cultural phenomenon of holding seances to summon souls from the great beyond, it was a little-known writer, John Dix, who recorded the emergence of a fresh coinage: “Every two or three years,” Dix wrote in 1853, “the Americans have a paroxysm of humbug … at the present time it is Spiritual-ism”. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, Dix’s comment is the first published use of the word ‘Spiritualism’, in the sense of channelling voices and visions from an invisible realm. Despite Dix’s suggestion that Spiritualism was likely a fleeting fad (“a paroxysm of humbug”), the modern psyche had well and truly been bitten by the bug. Before long, the existence of spirits with whom it was possible to communicate in the here-and-now was being passionately investigated as plausible by everyone from the leading evolutionary scientist Alfred Russel Wallace (who was eventually convinced) to the celebrated novelist and champion of empirical deduction, Arthur Conan Doyle (who needed little persuading).

Every age invents the language that it needs. Posterity will determine what it says about our own era that we have felt compelled to craft such words and phrases as ‘defriended’, ‘photobomb’, ‘flash mob’, ‘happy slapping’ and ‘selfie’. When our forebears in the 1850s found themselves at a loss for a term to describe the new cultural phenomenon of holding seances to summon souls from the great beyond, it was a little-known writer, John Dix, who recorded the emergence of a fresh coinage: “Every two or three years,” Dix wrote in 1853, “the Americans have a paroxysm of humbug … at the present time it is Spiritual-ism”. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, Dix’s comment is the first published use of the word ‘Spiritualism’, in the sense of channelling voices and visions from an invisible realm. Despite Dix’s suggestion that Spiritualism was likely a fleeting fad (“a paroxysm of humbug”), the modern psyche had well and truly been bitten by the bug. Before long, the existence of spirits with whom it was possible to communicate in the here-and-now was being passionately investigated as plausible by everyone from the leading evolutionary scientist Alfred Russel Wallace (who was eventually convinced) to the celebrated novelist and champion of empirical deduction, Arthur Conan Doyle (who needed little persuading). Where is Waldo?

Where is Waldo? I

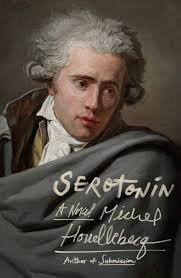

I That an author so notoriously sex-obsessed should concern himself with something as wholesome as ‘happiness’ looks, at first sight, like something of a contradiction. But Houellebecq was never really a hedonist. While often gratuitously graphic, his sex scenes are notably listless: related in blandly functional prose, they are conspicuously devoid of eroticism or joy. What some have interpreted as licentiousness could in fact be seen as the inverted prudery of the repressed social conservative. In Houellebecq’s fiction the libido, whether waxing or waning, is a problem to be overcome.

That an author so notoriously sex-obsessed should concern himself with something as wholesome as ‘happiness’ looks, at first sight, like something of a contradiction. But Houellebecq was never really a hedonist. While often gratuitously graphic, his sex scenes are notably listless: related in blandly functional prose, they are conspicuously devoid of eroticism or joy. What some have interpreted as licentiousness could in fact be seen as the inverted prudery of the repressed social conservative. In Houellebecq’s fiction the libido, whether waxing or waning, is a problem to be overcome. My wife and I never spent much time talking about whether we wanted to have children. It was clear to both of us that we did, and our only concern was that we might not be able to. Yet if you had asked me why I wanted to have children, I would not have had anything very articulate to say. Nor did that fact bother me. Having children just seemed like the natural next step, and I felt no need to have or give reasons.

My wife and I never spent much time talking about whether we wanted to have children. It was clear to both of us that we did, and our only concern was that we might not be able to. Yet if you had asked me why I wanted to have children, I would not have had anything very articulate to say. Nor did that fact bother me. Having children just seemed like the natural next step, and I felt no need to have or give reasons. Of course, every revolution is unique and comparisons between them do not always yield useful insights. But

Of course, every revolution is unique and comparisons between them do not always yield useful insights. But