by Dwight Furrow

It’s fashionable to criticize wine critics for a variety of sins: they’re biased, their scores don’t mean anything, and their jargon is unintelligible according to the critics of critics. Shouldn’t we just drink what we like? Who cares what critics think? In fact, whether the object is literature, painting, film, music, or wine, criticism is important for establishing evaluative standards and maintaining a dialogue about what is worth experiencing and why. The following is an account of how wine criticism aids wine appreciation by way of providing an account of wine appreciation.

It’s fashionable to criticize wine critics for a variety of sins: they’re biased, their scores don’t mean anything, and their jargon is unintelligible according to the critics of critics. Shouldn’t we just drink what we like? Who cares what critics think? In fact, whether the object is literature, painting, film, music, or wine, criticism is important for establishing evaluative standards and maintaining a dialogue about what is worth experiencing and why. The following is an account of how wine criticism aids wine appreciation by way of providing an account of wine appreciation.

Wine critics engage in a variety of activities. They evaluate wines by saying whether they are good or bad, often in order to advise readers about which wines they should purchase or seek to experience. Via their tasting notes, they guide their reader’s perceptions of a wine getting them to taste something they otherwise might have missed. Critics explain winemaking and viticultural practices, feature winemakers and explain how their inspiration or approach to winemaking influences their wines. They discuss styles of winemaking, changes in those styles as they occur, and new developments in the wine world. They discuss the quality of vintages, the characteristics of varietals and wine regions, and describe their own reactions to a wine.

The most plausible goal that ties all these activities together is that the critic aims to help her readers appreciate the wines about which she writes. Wine criticism is not just loosely related to wine appreciation; the purpose of wine criticism is to aid appreciation and thus we need an account of what it means to appreciate a wine. Read more »

Do contemporary approaches to translation tell us something about our times?

Do contemporary approaches to translation tell us something about our times? On Oct. 29, 2018, Lion Air Flight 610 taxied toward the runway at the main airport in Jakarta, Indonesia, carrying 189 people bound for Bangka Island, a short flight away. The airplane was the latest version of the Boeing 737, a gleaming new 737 Max that was delivered merely three months before. The captain was a 31-year-old Indian named Bhavye Suneja, who did his initial flight training at a small and now-defunct school in San Carlos, Calif., and opted for an entry-level job with Lion Air in 2011. Lion Air is an aggressive airline that dominates the rapidly expanding Indonesian market in low-cost air travel and is one of Boeing’s largest customers worldwide. It is known for hiring inexperienced pilots — most of them recent graduates of its own academy — and for paying them little and working them hard. Pilots like Suneja who come from the outside typically sign on in the hope of building hours and moving on to a better job. Lion Air gave him some simulator time and a uniform, put him into the co-pilot’s seat of a 737 and then made him a captain sooner than a more conventional airline would have. Nonetheless, by last Oct. 29, Suneja had accumulated 6,028 hours and 45 minutes of flight time, so he was no longer a neophyte. On the coming run, it would be his turn to do the flying.

On Oct. 29, 2018, Lion Air Flight 610 taxied toward the runway at the main airport in Jakarta, Indonesia, carrying 189 people bound for Bangka Island, a short flight away. The airplane was the latest version of the Boeing 737, a gleaming new 737 Max that was delivered merely three months before. The captain was a 31-year-old Indian named Bhavye Suneja, who did his initial flight training at a small and now-defunct school in San Carlos, Calif., and opted for an entry-level job with Lion Air in 2011. Lion Air is an aggressive airline that dominates the rapidly expanding Indonesian market in low-cost air travel and is one of Boeing’s largest customers worldwide. It is known for hiring inexperienced pilots — most of them recent graduates of its own academy — and for paying them little and working them hard. Pilots like Suneja who come from the outside typically sign on in the hope of building hours and moving on to a better job. Lion Air gave him some simulator time and a uniform, put him into the co-pilot’s seat of a 737 and then made him a captain sooner than a more conventional airline would have. Nonetheless, by last Oct. 29, Suneja had accumulated 6,028 hours and 45 minutes of flight time, so he was no longer a neophyte. On the coming run, it would be his turn to do the flying. If we try to map out an East-West divide for the global political developments of the last decade or so, we might end up with this: the East-West divide is not exactly what it was during the Cold War. It is now a divide between liberal and ‘illiberal’ democracies, and the ideas and undemocratic impulses that have recently come to represent the East have also more recently become ascendant in parts of the West—and also parts of the South—under governments that are further rightwing or leftwing than the norm.

If we try to map out an East-West divide for the global political developments of the last decade or so, we might end up with this: the East-West divide is not exactly what it was during the Cold War. It is now a divide between liberal and ‘illiberal’ democracies, and the ideas and undemocratic impulses that have recently come to represent the East have also more recently become ascendant in parts of the West—and also parts of the South—under governments that are further rightwing or leftwing than the norm. Jonathan Safran Foer’s second book of nonfiction is an eye-opening collection of mostly short essays expressing both despair and hope over the climate crisis, especially around individual choice. It’s a wide-ranging book — there are tributes to grandparents and sons, as well as musings on suicide, family, effort, sense and much more — but it has a point, and that is to persuade us to eat fewer animal products.

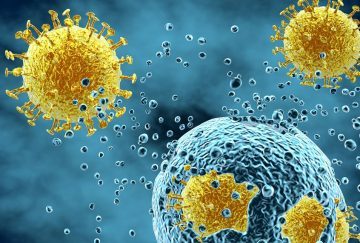

Jonathan Safran Foer’s second book of nonfiction is an eye-opening collection of mostly short essays expressing both despair and hope over the climate crisis, especially around individual choice. It’s a wide-ranging book — there are tributes to grandparents and sons, as well as musings on suicide, family, effort, sense and much more — but it has a point, and that is to persuade us to eat fewer animal products. Despite the common cold being so — well — common, researchers have never succeeded in the long dream of curing or immunizing against the array of rhinoviruses that generally cause it. Though the common cold generally does not kill those who are not infirm or immunocompromised, it costs billions in lost time and energy. Now, new research hints that science might be closing in on the cold. In a study to be

Despite the common cold being so — well — common, researchers have never succeeded in the long dream of curing or immunizing against the array of rhinoviruses that generally cause it. Though the common cold generally does not kill those who are not infirm or immunocompromised, it costs billions in lost time and energy. Now, new research hints that science might be closing in on the cold. In a study to be Typically for Smith, portents and symbols lurk in unexpected places, and everyday objects become freighted with meaning. Photographing them with her trusty Polaroid camera, she basks in the memories evoked by her father’s cup, a motel sign, a suit worn by the artist Joseph Beuys and a book of poems by Allen Ginsberg. She imagines her old chum Ginsberg fearlessly grappling with the current political turmoil. He “would have jumped right in, using his voice in its full capacity, encouraging all to be vigilant, to mobilise, to vote, and if need be, dragged into a paddy wagon, peacefully disobedient”.

Typically for Smith, portents and symbols lurk in unexpected places, and everyday objects become freighted with meaning. Photographing them with her trusty Polaroid camera, she basks in the memories evoked by her father’s cup, a motel sign, a suit worn by the artist Joseph Beuys and a book of poems by Allen Ginsberg. She imagines her old chum Ginsberg fearlessly grappling with the current political turmoil. He “would have jumped right in, using his voice in its full capacity, encouraging all to be vigilant, to mobilise, to vote, and if need be, dragged into a paddy wagon, peacefully disobedient”. YEARS AGO, I began to run into the claim that we are all storytellers. Evidently, storytelling was a primal communal function for humanity. I was assured that we’ve been telling each other stories since the beginning of time. I felt a churlish resistance to these proclamations, possibly because one might well decide that being human doesn’t mean one should subscribe, without discomfiture, to everything the human race is collectively doing at any given point. Storytelling shouldn’t be guaranteed an aura simply because humans have been at it from the beginning of history.

YEARS AGO, I began to run into the claim that we are all storytellers. Evidently, storytelling was a primal communal function for humanity. I was assured that we’ve been telling each other stories since the beginning of time. I felt a churlish resistance to these proclamations, possibly because one might well decide that being human doesn’t mean one should subscribe, without discomfiture, to everything the human race is collectively doing at any given point. Storytelling shouldn’t be guaranteed an aura simply because humans have been at it from the beginning of history. Devotees of the darker forms of fantastika know that much of the best work originates with small publishers, often in print runs of just a few hundred copies. So don’t delay in checking out Sarob Press’s

Devotees of the darker forms of fantastika know that much of the best work originates with small publishers, often in print runs of just a few hundred copies. So don’t delay in checking out Sarob Press’s

In 1969, Margaret Rossiter, then 24 years old, was one of the few women enrolled in a graduate program at Yale devoted to the history of science. Every Friday, Rossiter made a point of attending a regular informal gathering of her department’s professors and fellow students. Usually, at those late afternoon meetings, there was beer-drinking, which Rossiter did not mind, but also pipe-smoking, which she did, and joke-making, which she might have enjoyed except that the brand of humor generally escaped her. Even so, she kept showing up, fighting to feel accepted in a mostly male enclave, fearful of being written off in absentia.

In 1969, Margaret Rossiter, then 24 years old, was one of the few women enrolled in a graduate program at Yale devoted to the history of science. Every Friday, Rossiter made a point of attending a regular informal gathering of her department’s professors and fellow students. Usually, at those late afternoon meetings, there was beer-drinking, which Rossiter did not mind, but also pipe-smoking, which she did, and joke-making, which she might have enjoyed except that the brand of humor generally escaped her. Even so, she kept showing up, fighting to feel accepted in a mostly male enclave, fearful of being written off in absentia. Kendi, like any good academic, is clear about his terms and definitions. He believes that a racist is someone who supports “a racist policy through their actions or inaction or expressing a racist idea,” while an antiracist is one who supports “an antiracist policy through their actions or expressing an antiracist idea.” Most of us, he concludes, hold both racist and antiracist views. But our beliefs are not necessarily fixed and immutable. “‘Racist’ and ‘antiracist’ are like peelable name tags that are placed and replaced based on what someone is doing … in each moment. These are not permanent tattoos.” In other words, our views and positions can change – as the evolution of his own thinking demonstrates. He calls policies that increase racial disparities “racist” while policies that reduce such disparities are “antiracist.” So affirmative action policies in college admissions designed to increase the enrollment of students of color are antiracist. (Presumably this means that legacy preferences in admissions, which do not reduce racial disparities and indeed may reinforce them, are racist.) Working to repeal the Affordable Care Act is racist because doing so would increase racial disparities in health care. “Do-nothing climate policy is racist policy, since the predominately non-White global south is being victimized by climate change more than the Whiter global north.”

Kendi, like any good academic, is clear about his terms and definitions. He believes that a racist is someone who supports “a racist policy through their actions or inaction or expressing a racist idea,” while an antiracist is one who supports “an antiracist policy through their actions or expressing an antiracist idea.” Most of us, he concludes, hold both racist and antiracist views. But our beliefs are not necessarily fixed and immutable. “‘Racist’ and ‘antiracist’ are like peelable name tags that are placed and replaced based on what someone is doing … in each moment. These are not permanent tattoos.” In other words, our views and positions can change – as the evolution of his own thinking demonstrates. He calls policies that increase racial disparities “racist” while policies that reduce such disparities are “antiracist.” So affirmative action policies in college admissions designed to increase the enrollment of students of color are antiracist. (Presumably this means that legacy preferences in admissions, which do not reduce racial disparities and indeed may reinforce them, are racist.) Working to repeal the Affordable Care Act is racist because doing so would increase racial disparities in health care. “Do-nothing climate policy is racist policy, since the predominately non-White global south is being victimized by climate change more than the Whiter global north.” The first agreement we should make is: don’t call them soap operas,” Dr Arzu Ozturkmen, who teaches oral history at Boğaziçi University in Istanbul, scolds me. “We are very much against this.” What

The first agreement we should make is: don’t call them soap operas,” Dr Arzu Ozturkmen, who teaches oral history at Boğaziçi University in Istanbul, scolds me. “We are very much against this.” What  One of the most radical and important ideas in the history of physics came from an unknown graduate student who wrote only one paper, got into arguments with physicists across the Atlantic as well as his own advisor, and left academia after graduating without even applying for a job as a professor. Hugh Everett’s story is one of many fascinating tales that add up to the astonishing history of quantum mechanics, the most fundamental physical theory we know of.

One of the most radical and important ideas in the history of physics came from an unknown graduate student who wrote only one paper, got into arguments with physicists across the Atlantic as well as his own advisor, and left academia after graduating without even applying for a job as a professor. Hugh Everett’s story is one of many fascinating tales that add up to the astonishing history of quantum mechanics, the most fundamental physical theory we know of. Understanding American politics has become increasingly confusing as the old party labels have lost much of their meaning. A simplistic Left vs. Right worldview no longer captures the complexity of what’s going on. As the authors of the October 2017 “Pew Survey of American Political Typologies”

Understanding American politics has become increasingly confusing as the old party labels have lost much of their meaning. A simplistic Left vs. Right worldview no longer captures the complexity of what’s going on. As the authors of the October 2017 “Pew Survey of American Political Typologies”