Month: September 2019

The Ebbing Language

Sadiqa de Meijer at Poetry Magazine:

Afval is not offal, but garbage.

Afval is not offal, but garbage.

A blad is not a blade but a leaf, and also a sheet when referring to paper.

To huil is not to howl but to cry.

A geest is not so much a ghost as a spirit, and is also used for genie, which English has adapted instead from the Arabic jinni.

A fles is a bottle, which probably has something to do with a flask. A rozenbottel is a rose hip.

And in a very strange confluence, an eekhoorn, which is pronounced almost exactly like acorn, is a squirrel.

Boom, a tree. Tree, a step of the stairs. Stairs, a trap. Trap, a val, which also means fall, perhaps because of those archaic traps, holes dug on forest trails and covered with sticks and leaves. The season of fall, herfst.

more here.

The Man Who Thought He Could Define Madness

Not only was hysteria a disease of the body, but so was the susceptibility to hypnotic suggestion. In other words, according to Charcot, only true hysterics could attain the postures and maintain the poses of artificial hysteria. These could not be faked, so they had to be a pathological sign connected to real hysteria, even diagnostic of it. He called it le grand hypnotisme.

In 1882, Charcot presented this theory to the French Academy of Sciences as part of his bid for membership. The academy had already accepted his claim for the status of hysteria as a true disease on the strength of his reputation, although without much enthusiasm. They also signed off on his description of grand hypnotism, despite widespread skepticism. The idea had almost no support outside of Paris. According to Charcot’s critics, his four stages of hysteria and three-act demonstrations of hypnosis could be observed only at the Salpêtrière, or in patients who had lived there and had learned the choreography.

more here.

Samuel Barber’s Knoxville: Summer of 1915

Sudip Bose at The American Scholar:

“That was exactly my childhood!” said Eleanor Steber of Barber’s work and Agee’s text, remembering her upbringing in Wheeling, West Virginia. Another superb interpreter of Knoxville: Summer of 1915, Leontyne Price, born in Laurel, Mississippi, had a similar response: “it expresses everything I know about my roots and about my mama and father … my home town. … You can smell the South in it.” Why has Barber’s piece appealed to so many people from such different backgrounds—irrespective of race, wealth, or region? The text, a poetic hymn to both nostalgia and existential insecurity, does address questions of universal appeal, but I suspect that the music’s subtle bluesy streaks increases its familiarity and allure. Barber may have been the consummate continental Romantic, but he never sounded so idiomatically American as he does in Knoxville: Summer of 1915. The work speaks to us all. In its journey from innocence to experience, it deals profoundly with our loneliness in the world, with how we reckon with growing up, a business made all the harder when the last thing we come to learn is exactly who we are.

“That was exactly my childhood!” said Eleanor Steber of Barber’s work and Agee’s text, remembering her upbringing in Wheeling, West Virginia. Another superb interpreter of Knoxville: Summer of 1915, Leontyne Price, born in Laurel, Mississippi, had a similar response: “it expresses everything I know about my roots and about my mama and father … my home town. … You can smell the South in it.” Why has Barber’s piece appealed to so many people from such different backgrounds—irrespective of race, wealth, or region? The text, a poetic hymn to both nostalgia and existential insecurity, does address questions of universal appeal, but I suspect that the music’s subtle bluesy streaks increases its familiarity and allure. Barber may have been the consummate continental Romantic, but he never sounded so idiomatically American as he does in Knoxville: Summer of 1915. The work speaks to us all. In its journey from innocence to experience, it deals profoundly with our loneliness in the world, with how we reckon with growing up, a business made all the harder when the last thing we come to learn is exactly who we are.

more here.

Friday Poem

Perhaps the World Ends Here

The world begins at a kitchen table. No matter what, we must eat

….. to live.

The gifts of earth are brought and prepared, set on the table. So it

….. has been since creation, and it will go on.

We chase chickens or dogs away from it. Babies teethe at the corners.

….. They scrape their knees under it.

It is here that children are given instructions on what it means to

….. be human. We make men at it, we make women.

At this table we gossip, recall enemies and the ghosts of lovers.

Our dreams drink coffee with us as they put their arms around

….. our children. They laugh with us at our poor falling-down

….. selves and as we put ourselves back together once again at the

….. table.

This table has been a house in the rain, an umbrella in the sun.

Wars have begun and ended at this table. It is a place to hide in

….. the shadow of terror. A place to celebrate the terrible victory.

We have given birth on this table, and have prepared our parents

….. for burial here.

At this table we sing with joy, with sorrow. We pray of suffering

….. and remorse. We give thanks.

Perhaps the world will end at the kitchen table, while we are

….. laughing and crying, eating of the last sweet bite.

by Joy Harjo

from The Woman Who Fell From the Sky

© 1994

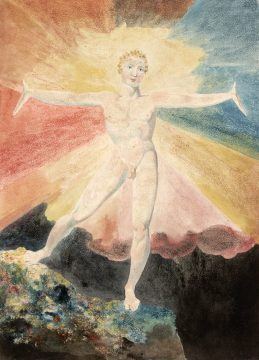

William Blake’s design innovations

Michael Prodger in New Statesman:

On February 1818, Samuel Taylor Cole-ridge was sent a copy of Songs of Innocence, William Blake’s first illustrated book of poems, which had been published some 30 years earlier. He was both impressed and discomfited by what he read. “You may smile at my calling another Poet a Mystic,” Coleridge, by then a fully fledged opium addict, wrote to a friend, “but verily I am in the very mire of commonplace common sense compared with Mr Blake.” Coleridge was not, of course, the first or last person to be mired.

On February 1818, Samuel Taylor Cole-ridge was sent a copy of Songs of Innocence, William Blake’s first illustrated book of poems, which had been published some 30 years earlier. He was both impressed and discomfited by what he read. “You may smile at my calling another Poet a Mystic,” Coleridge, by then a fully fledged opium addict, wrote to a friend, “but verily I am in the very mire of commonplace common sense compared with Mr Blake.” Coleridge was not, of course, the first or last person to be mired.

Blake’s offbeat character – from his naturism and convoluted, self-invented cosmology to his visions of angels sitting in trees and his political and religious nonconformism – forms a carapace so tough as to be nigh-on impenetrable. The fact that his quirks were not so much elements of the man but the man himself means that he can be too daunting to comprehend properly. He once said of his illustrated poems that “My style of designing is a species by itself” and Blake too can perhaps be best characterised as a species in himself.

Whatever Blake was – poet, prophet and sage, or “Rebel, Radical, Revolutionary” as the poster to Tate Britain’s extraordinary new survey of his career somewhat sensationally puts it – he was primarily, and from first to last, a professional artist. For much of his life he spent his days as a highly regarded freelance commercial engraver; his evenings he gave over to his watercolours and relief etchings – intended as saleable products; and it was only late at night that he became a poet, composing in snatches when he had a few moments to spare.

More here.

The Crisis for Birds Is a Crisis for Us All

Fitzpatrick and Marra in The New York Times:

Nearly one-third of the wild birds in the United States and Canada have vanished since 1970, a staggering loss that suggests the very fabric of North America’s ecosystem is unraveling. The disappearance of 2.9 billion birds over the past nearly 50 years was reported today in the journal Science, a result of a comprehensive study by a team of scientists from seven research institutions in the United States and Canada.

Nearly one-third of the wild birds in the United States and Canada have vanished since 1970, a staggering loss that suggests the very fabric of North America’s ecosystem is unraveling. The disappearance of 2.9 billion birds over the past nearly 50 years was reported today in the journal Science, a result of a comprehensive study by a team of scientists from seven research institutions in the United States and Canada.

As ornithologists and the directors of two major research institutes that directed this study, even we were shocked by the results. We knew of well-documented losses among shorebirds and songbirds. But the magnitude of losses among 300 bird species was much larger than we had expected and alarmingly widespread across the continent.

What makes this study particularly compelling is the trustworthiness of the data. Birds are the best-studied group of wildlife; their populations have been carefully monitored over decades by scientists and citizen scientists alike. And in recent years, scientists have been able to track the volume of nighttime bird migrations through a network of 143 high-resolution weather radars. This study pulls all of that data together, and the results signal an unfolding crisis. More than half our grassland birds have disappeared, 717 million in all. Forests have lost more than one billion birds.

More here.

Michael Chabon: ‘Ulysses’ on Trial

Michael Chabon in the New York Review of Books:

It was a setup: a stratagem worthy of wily Ulysses himself.

The conspirators were Bennett Cerf, publisher and cofounder of Random House, and Morris Ernst, general counsel of the ACLU. The target was United States anti-obscenity law. The bait was a single copy of an English-language novel, printed in Dijon by Frenchmen who could not understand a word of it, bound in bright blue boards, and sold mail-order by the celebrated Paris bookshop Shakespeare and Company. When Cerf and Ernst first began to conspire in 1931, the novel, James Joyce’s Ulysses, was the most notorious book in the world.

“It is,” the editor of the London Sunday Express had written nine years earlier, sounding like H.P. Lovecraft describing Necronomicon:

the most infamously obscene book in ancient or modern literature….All the secret sewers of vice are canalized in its flood of unimaginable thoughts, images and pornographic words. And its unclean lunacies are larded with appalling and revolting blasphemies directed against the Christian religion and against the name of Christ—blasphemies hitherto associated with the most degraded orgies of Satanism and the Black Mass.

Regarded as a masterpiece by contemporary writers such as T.S. Eliot and Ernest Hemingway, celebrated for being as difficult to read as to obtain, Ulysses had been shocking the sensibilities of critics, censors, and readers from the moment it began to see print between 1918 and 1920, when four chapters were abortively serialized in the pages of a New York quarterly called The Little Review.

More here.

Evidence that quantum searches are an ordinary feature of electron behavior may explain the genetic code, one of the greatest puzzles in biology

From the MIT Technology Review:

Back in 1996, a quantum physicist at Bell Labs in New Jersey published a new recipe for searching through a database of N entries. Computer scientists have long known that this process takes around N steps because in the worst case, the last item on the list could be the one of interest.

Back in 1996, a quantum physicist at Bell Labs in New Jersey published a new recipe for searching through a database of N entries. Computer scientists have long known that this process takes around N steps because in the worst case, the last item on the list could be the one of interest.

However, this physicist, Lov Grover, showed how the strange rules of quantum mechanics allowed the search to be done in a number of steps equal to the square root of N.

That was a big deal. Searching databases is a foundational task in computer science, used for everything from finding telephone numbers to breaking cryptographic codes. So any speed-up is a significant advance.

Quantum mechanics provided an additional twist.

More here.

A New Collection Upends Conventional Wisdom About Migration

Parul Sehgal in the New York Times:

There’s a saying often attributed to the novelist John Gardner that there are really only two stories: A Person Goes on a Journey or A Stranger Comes to Town.

Which is, of course, the same story, just turned inside out. It’s the story of movement; of migration, its trauma or license, its challenge to one’s premises and moral coordinates, life and livelihood. In her Nobel Prize lecture, Toni Morrison recounted a folktale found across many cultures. A group of children visit a wise old woman, a storyteller or griot. “Tell us what it is to have no home in this place,” they ask. “To be set adrift from the one you knew. What it is to live at the edge of towns that cannot bear your company.”

“The Penguin Book of Migration Literature,” edited by Dohra Ahmad, has the startling distinction of being the first global anthology of migration literature, according to its publisher. Previous such collections have been “origin-specific,” devoted to particular diasporas, Ahmad writes; her book offers the opportunity for global comparison across history and genre. It includes excerpts from classics by Phillis Wheatley, Sam Selvon, Edwidge Danticat (who also contributes the foreword), Salman Rushdie, Marjane Satrapi and Zadie Smith, along with younger writers like the Nigerian novelist Sefi Atta and the Sudanese-American poet Safia Elhillo.

More here.

Carl June: A “living drug” that could change the way we treat cancer

Dynamicland and the Whimsical Digital Object

Olivia Kan-Sperling at Cabinet Magazine:

Six hours’ drive north of Disneyland, a building in downtown Oakland houses a kind of computer scientist’s version of the storied children’s amusement park. Its digital magic is of a less spectacular flavor, though; while Hollywood dreams of technofuturia in the style of vapory holograms, and Elon Musk promises to launch us skyward in machines of the old-school brushed-steel-and-silver variety, “Dynamicland” is composed of more modest materials. It’s neither VR, nor AR—just R. Like the early computers of the 1940s, Dynamicland is a computer the size of a room, but without the typical trappings of digital hi-tech. Post-its, magic markers, scissors, and staplers are the primary technologies programmers work with here, augmented by projections cast onto paper and tables. The room looks like a typical co-working space: bright couches, Ikea-hued tables, whiteboards. But the computer, here, is the room; its “smart” ceilings are embedded with cameras that process the visual data that constitute Dynamicland’s computer programs.

Six hours’ drive north of Disneyland, a building in downtown Oakland houses a kind of computer scientist’s version of the storied children’s amusement park. Its digital magic is of a less spectacular flavor, though; while Hollywood dreams of technofuturia in the style of vapory holograms, and Elon Musk promises to launch us skyward in machines of the old-school brushed-steel-and-silver variety, “Dynamicland” is composed of more modest materials. It’s neither VR, nor AR—just R. Like the early computers of the 1940s, Dynamicland is a computer the size of a room, but without the typical trappings of digital hi-tech. Post-its, magic markers, scissors, and staplers are the primary technologies programmers work with here, augmented by projections cast onto paper and tables. The room looks like a typical co-working space: bright couches, Ikea-hued tables, whiteboards. But the computer, here, is the room; its “smart” ceilings are embedded with cameras that process the visual data that constitute Dynamicland’s computer programs.

more here.

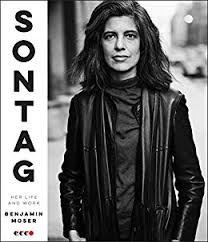

Sontag: Her Life

Joan Smith at Literary Review:

‘Many who encountered the actual woman were disappointed to discover a reality far short of the glorious myth,’ Moser writes in his introduction. ‘Disappointment with her, indeed, is a prominent theme in memoirs of Sontag, not to mention in her own private writings.’ It is a salutary warning to readers who have bought into the notion of the dazzling, supremely confident intellectual. Eight hundred exhausting pages later, Sontag emerges as one of those irredeemably unhappy people, endlessly lurching between narcissism and self-hatred, who leave a string of uncomprehending friends, relatives and lovers in their wake. She wasn’t even interested in personal hygiene or health, forgetting to wash, wearing the same clothes for days at a time, smoking heavily and gorging herself on food at other people’s expense. A friend once arrived late for dinner with her at Petrossian on 58th Street, only to find that Sontag had already gone home, leaving him with the bill for the ‘sumptuous, multi-course caviar dinner’ she had consumed.

‘Many who encountered the actual woman were disappointed to discover a reality far short of the glorious myth,’ Moser writes in his introduction. ‘Disappointment with her, indeed, is a prominent theme in memoirs of Sontag, not to mention in her own private writings.’ It is a salutary warning to readers who have bought into the notion of the dazzling, supremely confident intellectual. Eight hundred exhausting pages later, Sontag emerges as one of those irredeemably unhappy people, endlessly lurching between narcissism and self-hatred, who leave a string of uncomprehending friends, relatives and lovers in their wake. She wasn’t even interested in personal hygiene or health, forgetting to wash, wearing the same clothes for days at a time, smoking heavily and gorging herself on food at other people’s expense. A friend once arrived late for dinner with her at Petrossian on 58th Street, only to find that Sontag had already gone home, leaving him with the bill for the ‘sumptuous, multi-course caviar dinner’ she had consumed.

So much for the gossip, but what about the writing? Moser’s book offers such a gripping account of a profoundly damaged human being, trapped in a cycle of repetition, that it would be easy to forget the fact that Sontag was a writer.

more here.

Wagner: Totalizing Master of Endless Melodies

Gundula Kreuzer at the TLS:

This focus on drama was fostered by Wagner’s upbringing, which included relatively little musical education. A painter and actor, his step-father Ludwig Geyer had taken young Richard to the theatre. Wagner did for a short while study composition in his home town of Leipzig. But he was never a proficient instrumentalist, which narrowed his path to a musical career. With what became his typical mixture of determination and cunning, he made a virtue out of necessity and simply declared the orchestra the grandest of instruments. (Indeed, he later wrote one of the first modern conducting manuals.) Above all, though, he learned on the job. In early 1833, at the age of nineteen, he began a series of seasonal engagements as chorus master and music director at various minor theatres as well as a touring company. These gave him valuable insights into the state of provincial opera performances, introduced him to the actress Minna Planer (soon to become his first wife), and opened the opportunity to mount a first operatic attempt. But he could not support the comfortable, silk-bedecked lifestyle he craved. Escaping his creditors, he spent two poverty-stricken but formative years in Paris, then the centre of the operatic world.

This focus on drama was fostered by Wagner’s upbringing, which included relatively little musical education. A painter and actor, his step-father Ludwig Geyer had taken young Richard to the theatre. Wagner did for a short while study composition in his home town of Leipzig. But he was never a proficient instrumentalist, which narrowed his path to a musical career. With what became his typical mixture of determination and cunning, he made a virtue out of necessity and simply declared the orchestra the grandest of instruments. (Indeed, he later wrote one of the first modern conducting manuals.) Above all, though, he learned on the job. In early 1833, at the age of nineteen, he began a series of seasonal engagements as chorus master and music director at various minor theatres as well as a touring company. These gave him valuable insights into the state of provincial opera performances, introduced him to the actress Minna Planer (soon to become his first wife), and opened the opportunity to mount a first operatic attempt. But he could not support the comfortable, silk-bedecked lifestyle he craved. Escaping his creditors, he spent two poverty-stricken but formative years in Paris, then the centre of the operatic world.

more here.

Thursday Poem

Elevator Music

A tune with no more substance than the air,

performed on underwater instruments,

is proper to this short lift from the earth.

It hovers as we draw into ourselves

and turn our reverent eyes toward the lights

that count us to our various destinies.

We’re all in this together, the song says,

and later we’ll descend. The melody

is like a name we don’t recall just now

that still keeps on insisting it is there.

by Henry Taylor

from Poetry 180

Random House 2003

Will there ever be a cure for chronic pain?

Sophie Elmhirst in MIL:

Peter McNaughton, a professor of pharmacology at King’s College London, is a devoted optimist. He acknowledges that his positivity can sometimes seem irrational, but he also knows that without it he wouldn’t have achieved all that he has. And what he’s achieved is quite possibly monumental. After decades of research into the cellular basis of chronic pain, McNaughton believes he has discovered the fundamentals of a drug that might eradicate it. If he’s right, he could transform millions, even billions, of lives. What more could anyone hope for than a world without pain?

Peter McNaughton, a professor of pharmacology at King’s College London, is a devoted optimist. He acknowledges that his positivity can sometimes seem irrational, but he also knows that without it he wouldn’t have achieved all that he has. And what he’s achieved is quite possibly monumental. After decades of research into the cellular basis of chronic pain, McNaughton believes he has discovered the fundamentals of a drug that might eradicate it. If he’s right, he could transform millions, even billions, of lives. What more could anyone hope for than a world without pain?

McNaughton, nearly 70, is long-limbed, grey-haired and bespectacled. Though he has lived in London for decades, his voice still carries the cheery cadence of his native New Zealand. He wears blue Levis and black Nikes and delights in a late-blooming informality after years of heading university departments and turning up in a suit. Now, running his own lab, he can dress as he likes. On a Friday morning in April he waited for his young team to arrive at the modern, red-brick building in south London where he conducts his research. (McNaughton is always the first to arrive.) Today the team was assembled to hear a presentation by Rafaela Lone, a Brazilian scientist, who had spent the past six months in McNaughton’s lab breeding mice with symptoms that mimic fibromyalgia, a long-term condition that causes widespread pain and chronic fatigue. Lone explained that her mother had suffered from fibromyalgia for seven years. Her life had been reduced to a misery of symptoms ranging from urinary-tract infections to intense sensitivity to cold. Some days were bear-able; on others she couldn’t get out of bed. “She learns how to hold the pain,” said Lone.

McNaughton looked aggrieved at this (he finds it so hard to tolerate other people’s discomfort that, when his grandchildren come to stay, he lets them sleep in his bed because he can’t bear to disappoint them). But there was hope. Lone’s slides revealed her preliminary findings. Using genetic and pharmacological methods based on McNaughton’s research, she had achieved a consistent eradication of the mice’s pain. McNaughton looked exultant: “It’s really worked spectacularly well, hasn’t it?”

His eureka moment occurred back in 2010.

More here.

The Strange Persistence of First Languages

Julie Sedivy in Nautilus:

Several years ago, my father died as he had done most things throughout his life: without preparation and without consulting anyone. He simply went to bed one night, yielded his brain to a monstrous blood clot, and was found the next morning lying amidst the sheets like his own stone monument. It was hard for me not to take my father’s abrupt exit as a rebuke. For years, he’d been begging me to visit him in the Czech Republic, where I’d been born and where he’d gone back to live in 1992. Each year, I delayed. I was in that part of my life when the marriage-grad-school-children-career-divorce current was sweeping me along with breath-sucking force, and a leisurely trip to the fatherland seemed as plausible as pausing the flow of time. Now my dad was shrugging at me from beyond— “You see, you’ve run out of time.”

Several years ago, my father died as he had done most things throughout his life: without preparation and without consulting anyone. He simply went to bed one night, yielded his brain to a monstrous blood clot, and was found the next morning lying amidst the sheets like his own stone monument. It was hard for me not to take my father’s abrupt exit as a rebuke. For years, he’d been begging me to visit him in the Czech Republic, where I’d been born and where he’d gone back to live in 1992. Each year, I delayed. I was in that part of my life when the marriage-grad-school-children-career-divorce current was sweeping me along with breath-sucking force, and a leisurely trip to the fatherland seemed as plausible as pausing the flow of time. Now my dad was shrugging at me from beyond— “You see, you’ve run out of time.”

His death underscored another loss, albeit a far more subtle one: that of my native tongue. Czech was the only language I knew until the age of 2, when my family began a migration westward, from what was then Czechoslovakia through Austria, then Italy, settling eventually in Montreal, Canada. Along the way, a clutter of languages introduced themselves into my life: German in preschool, Italian-speaking friends, the francophone streets of East Montreal. Linguistic experience congealed, though, once my siblings and I started school in English. As with many immigrants, this marked the time when English became, unofficially and over the grumbling of my parents (especially my father), our family language—the time when Czech began its slow retreat from my daily life.

Many would applaud the efficiency with which we settled into English—it’s what exemplary immigrants do. But between then and now, research has shown the depth of the relationship all of us have with our native tongues—and how traumatic it can be when that relationship is ruptured. Spurred by my father’s death, I returned to the Czech Republic hoping to reconnect to him. In doing so, I also reconnected with my native tongue, and with parts of my identity that I had long ignored.

More here.

Do Not Trust Your Arguments

Tanner Greer in The Scholar’s Stage:

In last month’s post on Chinese attitudes towards Hong Kong I had cause to mention Dan Sperber and Hugo Mercier’s book The Enigma of Reason. At some point I probably ought to devote an entire post to a review of the book; its ideas are subtler and logic more involved than one paragraph glosses (or even most of its newspaper reviews) can give justice to. A running theme throughout the book, is that in experimental settings and in “real life” human capacity for reason is not optimized for the pursuit of abstract truth. Mercier and Sperber suggest that this is because reason did not evolve for that end. Reasoning’s role is essentially a social one—at the level of the individual it is not about deciding what to do, but about justifying what we do.

In last month’s post on Chinese attitudes towards Hong Kong I had cause to mention Dan Sperber and Hugo Mercier’s book The Enigma of Reason. At some point I probably ought to devote an entire post to a review of the book; its ideas are subtler and logic more involved than one paragraph glosses (or even most of its newspaper reviews) can give justice to. A running theme throughout the book, is that in experimental settings and in “real life” human capacity for reason is not optimized for the pursuit of abstract truth. Mercier and Sperber suggest that this is because reason did not evolve for that end. Reasoning’s role is essentially a social one—at the level of the individual it is not about deciding what to do, but about justifying what we do.

What we decide to do is for the most part entirely intuitive. As Mercier and Sperber see it, our decisions are the products of mental subsystems as opaque to us as the mysterious mechanisms that classify what we see as “beautiful” or “ugly,” determine what we are doing as “boring” or “fun,” and judge what others are doing as “admirable” or “disgusting.” Although his brain will supply the child with reasons for why he likes to watch Star Wars, the teenager with reasons for why she favors purple eye-liner, and the lover with reasons for doting upon his beloved, these thoughts are not the actual cause of the behavior in question. They are justifications. They are seized upon and articulated by the brain not to make us aware of why we make our decisions, but to make it possible for us to justify and explain our behavior to others.

Sperber and Mercier confirm this general thesis through dozens of experiments and lots of clever thinking.

More here.

New Proof Solves 80-Year-Old Irrational Number Problem

Leila Sloman in Scientific American:

Most people rarely deal with irrational numbers—it would be, well, irrational, as they run on forever, and representing them accurately requires an infinite amount of space. But irrational constants such as π and √2—numbers that cannot be reduced to a simple fraction—frequently crop up in science and engineering. These unwieldy numbers have plagued mathematicians since the ancient Greeks; indeed, legend has it that Hippasus was drowned for suggesting irrationals existed. Now, though, a nearly 80-year-old quandary about how well they can be approximated has been solved.

Most people rarely deal with irrational numbers—it would be, well, irrational, as they run on forever, and representing them accurately requires an infinite amount of space. But irrational constants such as π and √2—numbers that cannot be reduced to a simple fraction—frequently crop up in science and engineering. These unwieldy numbers have plagued mathematicians since the ancient Greeks; indeed, legend has it that Hippasus was drowned for suggesting irrationals existed. Now, though, a nearly 80-year-old quandary about how well they can be approximated has been solved.

Many people conceptualize irrational numbers by rounding them to fractions or decimals: estimating π as 3.14, which is equivalent to 157/50, leads to widespread celebration of Pi Day on March 14th. Yet a different approximation, 22/7, is easier to wrangle and closer to π. This prompts the question: Is there a limit to how simple and accurate these approximations can ever get? And can we choose a fraction in any form we want?

More here.

The coalitions that sustained the traditional left parties in the West have collapsed

Yascha Mounk in Democracy:

Across the world, the right has, for the past decades, celebrated a remarkable string of successes. Far-right populists are now in power in countries from the United States to India, and from Turkey to Brazil. Even most of the democracies in which right-wing extremists remain comparatively weak are ruled by right-of-center, or at most centrist, leaders: Angela Merkel is now in the 14th year of her chancellorship in Germany, Scott Morrison was recently reelected in Australia, and Emmanuel Macron is the President of France.

Across the world, the right has, for the past decades, celebrated a remarkable string of successes. Far-right populists are now in power in countries from the United States to India, and from Turkey to Brazil. Even most of the democracies in which right-wing extremists remain comparatively weak are ruled by right-of-center, or at most centrist, leaders: Angela Merkel is now in the 14th year of her chancellorship in Germany, Scott Morrison was recently reelected in Australia, and Emmanuel Macron is the President of France.

In politics, one party’s gain is virtually always another party’s loss. While the right is dominant in most countries, the number of democracies ruled by the left now stands near historic lows. Spain, Portugal, Denmark, and Mexico have leftist leaders. Canada might be added to the mix, though the incumbent faces an uphill battle to stay in power at upcoming elections. That’s about it.

A lot of ink (some of it my own) has, in the past years, been spilled to explain the remarkable success of the right. This singular focus has made it more difficult to understand the equally significant transformations that have been taking place on the left side of the political spectrum: the ongoing decline and fall of social democracy; the rise and rapid fall of the far left; and the recent rise of green and liberal parties.

More here.