Jean-Baptiste Del Amo at n+1:

DURING THE DAY, the pig units become like furnaces, and they barely cool down at night. Pigs are unable to sweat and have difficulty regulating their body temperature.

DURING THE DAY, the pig units become like furnaces, and they barely cool down at night. Pigs are unable to sweat and have difficulty regulating their body temperature.

Since they cannot wallow in mud, they sprawl listlessly in their own excrement, panting in distress. The men get up at daybreak, refill the drinking troughs, hose down the animals. They throw open the doors of the pig sheds in the hope that a through breeze might drive away the humidity and the stench, but this means they have deal with the blowflies and horseflies that swarm in and hover in clouds over the stalls, clustering around every orifice of the pigs. Before the sun has even risen, they are forced to fold doors.

The sons rake droppings from under the slatted floors and push the slurry into the drainage channels. The pig sheds are two thousand square meters, and the stalls are two meters by three, each containing between five to seven pigs shitting and wallowing in their excreta.

more here.

With the coming of the Third Reich, Nolde let the mask drop completely. He not only denounced his fellow artist Pechstein as a “Jew” (he wasn’t), but in the summer of 1933 drafted a plan, which he later destroyed, for how to remove Jews from German society. And unfortunately for him, plenty of other evidence has survived. In the autumn of 1938, for example, Nolde wrote that one could “understand” that “the operation for the removal of the Jews, who have burrowed so deep into all peoples” could not be carried out without “a lot of pain”. Not long afterwards, Nolde wrote to the Nazi press chief Otto Dietrich that he had spent his entire life fighting against the “too-great dominance of Jews in all matters artistic”. In November 1940, he praised Hitler’s speech on the anniversary of the failed Munich Beer Hall Putsch of 1923, especially the passages attacking “the Jews”.

With the coming of the Third Reich, Nolde let the mask drop completely. He not only denounced his fellow artist Pechstein as a “Jew” (he wasn’t), but in the summer of 1933 drafted a plan, which he later destroyed, for how to remove Jews from German society. And unfortunately for him, plenty of other evidence has survived. In the autumn of 1938, for example, Nolde wrote that one could “understand” that “the operation for the removal of the Jews, who have burrowed so deep into all peoples” could not be carried out without “a lot of pain”. Not long afterwards, Nolde wrote to the Nazi press chief Otto Dietrich that he had spent his entire life fighting against the “too-great dominance of Jews in all matters artistic”. In November 1940, he praised Hitler’s speech on the anniversary of the failed Munich Beer Hall Putsch of 1923, especially the passages attacking “the Jews”. About a century ago, a series of giant murals was unveiled in the Palace of Westminster depicting the “

About a century ago, a series of giant murals was unveiled in the Palace of Westminster depicting the “ The other day I fixed something—a rarity for me. The flotation device in the toilet water tank was rubbing against the side, getting stuck halfway up so that the tank didn’t fill completely. I own a hammer and know how to operate it. But I couldn’t fit it into the tank to whack the device back into place. Ditto for owning and using a wrench. It wouldn’t fit either. But fortunately I also own a plunger and I used its handle to push the floating thing back the other way, using the side of the tank as a fulcrum. It worked, although the device got bent so that the top of the tank didn’t quite fit. That overwhelmed me, so I called it a good day’s work. I was proud of myself. “There,” I thought smugly. “It’s not just chimps who can use tools.”

The other day I fixed something—a rarity for me. The flotation device in the toilet water tank was rubbing against the side, getting stuck halfway up so that the tank didn’t fill completely. I own a hammer and know how to operate it. But I couldn’t fit it into the tank to whack the device back into place. Ditto for owning and using a wrench. It wouldn’t fit either. But fortunately I also own a plunger and I used its handle to push the floating thing back the other way, using the side of the tank as a fulcrum. It worked, although the device got bent so that the top of the tank didn’t quite fit. That overwhelmed me, so I called it a good day’s work. I was proud of myself. “There,” I thought smugly. “It’s not just chimps who can use tools.” Consider the opening shots of the movie Human Desire, directed by Fritz Lang and released by Columbia Pictures in 1954. We see a man on a train. He’s the engineer. He sits at the front of the train, driving it along the tracks. His demeanor is one of comfort and ease. Then we move to another shot. The camera has been positioned at the side of the train looking forward. Another train comes into view moving toward us, on the opposite track. It seems, for a moment, that there is not enough space for the two trains to pass one another safely. A collision is imminent. But then, with a whoosh, the trains pass one another without incident. We’ve all experienced this fear as two trains pass at high speeds. The margin of error is so small. The violence of the rush of air smacking both trains is startling.

Consider the opening shots of the movie Human Desire, directed by Fritz Lang and released by Columbia Pictures in 1954. We see a man on a train. He’s the engineer. He sits at the front of the train, driving it along the tracks. His demeanor is one of comfort and ease. Then we move to another shot. The camera has been positioned at the side of the train looking forward. Another train comes into view moving toward us, on the opposite track. It seems, for a moment, that there is not enough space for the two trains to pass one another safely. A collision is imminent. But then, with a whoosh, the trains pass one another without incident. We’ve all experienced this fear as two trains pass at high speeds. The margin of error is so small. The violence of the rush of air smacking both trains is startling. I suspect most loyal Mindscape listeners have been exposed to the fact that I’ve written a new book,

I suspect most loyal Mindscape listeners have been exposed to the fact that I’ve written a new book,  Everything was unfolding as it usually does. The academics who gathered in Lisbon this summer for the International Society of Political Psychologists’ annual meeting had been politely listening for four days, nodding along as their peers took to the podium and delivered papers on everything from the explosion in conspiracy theories to the rise of authoritarianism.

Everything was unfolding as it usually does. The academics who gathered in Lisbon this summer for the International Society of Political Psychologists’ annual meeting had been politely listening for four days, nodding along as their peers took to the podium and delivered papers on everything from the explosion in conspiracy theories to the rise of authoritarianism. Has the behaviour of another person ever made you feel ashamed? Not because they set out to shame you but because they acted so virtuously that it made you feel inadequate by comparison. If so, then it is likely that, at least for a brief moment in time, you felt motivated to improve as a person. Perhaps you found yourself thinking that you should be kinder, tidier, less jealous, more hardworking or just generally better: to live up to your full potential. If the feeling was powerful enough, it might have changed your behaviour for a few minutes, days, weeks, months, years or a lifetime. Such change is the result of a mechanism I shall call ‘moral hydraulics’.

Has the behaviour of another person ever made you feel ashamed? Not because they set out to shame you but because they acted so virtuously that it made you feel inadequate by comparison. If so, then it is likely that, at least for a brief moment in time, you felt motivated to improve as a person. Perhaps you found yourself thinking that you should be kinder, tidier, less jealous, more hardworking or just generally better: to live up to your full potential. If the feeling was powerful enough, it might have changed your behaviour for a few minutes, days, weeks, months, years or a lifetime. Such change is the result of a mechanism I shall call ‘moral hydraulics’. A small clinical study in California has suggested for the first time that it might be possible to reverse the body’s epigenetic clock, which measures a person’s biological age. For one year, nine healthy volunteers took a cocktail of three common drugs — growth hormone and two diabetes medications — and on average shed 2.5 years of their biological ages, measured by analysing marks on a person’s genomes. The participants’ immune systems also showed signs of rejuvenation. The results were a surprise even to the trial organizers — but researchers caution that the findings are preliminary because the trial was small and did not include a control arm.

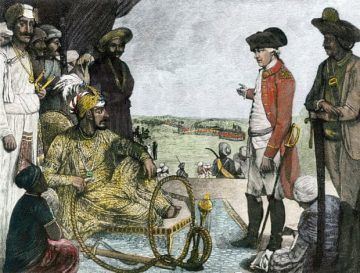

A small clinical study in California has suggested for the first time that it might be possible to reverse the body’s epigenetic clock, which measures a person’s biological age. For one year, nine healthy volunteers took a cocktail of three common drugs — growth hormone and two diabetes medications — and on average shed 2.5 years of their biological ages, measured by analysing marks on a person’s genomes. The participants’ immune systems also showed signs of rejuvenation. The results were a surprise even to the trial organizers — but researchers caution that the findings are preliminary because the trial was small and did not include a control arm. Power’s book didn’t offer much discussion of failure, of the limitations of intervention, even in places where it was unclear that American efforts could have succeeded. In Rwanda, which is often cited as an example of U.S. inaction, most of the killing was done so swiftly—eight hundred thousand people in three months—that it’s hard to imagine the American bureaucracy and military orchestrating a response quickly enough to make a difference, and then staying around long enough to insure that violence didn’t recur. But in 2002 the notion that America could police the world didn’t seem so far-fetched. nato had recently taken on three new members. China’s economy was a tenth of its present size. The World Trade Center had been destroyed, but the U.S. had toppled the Taliban government in Afghanistan. The invasion of Iraq was still a year away.

Power’s book didn’t offer much discussion of failure, of the limitations of intervention, even in places where it was unclear that American efforts could have succeeded. In Rwanda, which is often cited as an example of U.S. inaction, most of the killing was done so swiftly—eight hundred thousand people in three months—that it’s hard to imagine the American bureaucracy and military orchestrating a response quickly enough to make a difference, and then staying around long enough to insure that violence didn’t recur. But in 2002 the notion that America could police the world didn’t seem so far-fetched. nato had recently taken on three new members. China’s economy was a tenth of its present size. The World Trade Center had been destroyed, but the U.S. had toppled the Taliban government in Afghanistan. The invasion of Iraq was still a year away. So what is to be done? What might seem like an esoteric crisis in Augustinian scholarship suddenly reflects a crisis about how we think, and how that thinking might give rise to a whole host of other predicaments. In which case, perhaps the resolution of one can aid us in resolving the other. In Augustine’s case, Kenyon argues that we should approach him in a holistic way and cease strip-mining his work for this or that argument or literary trope. We should especially not get bogged down in attempts to historically recreate Augustine’s psyche, but turn to the “overarching arguments and rhetorical strategy instead of individual passages” and “prefer interpretations that make sense of a text as a whole.” What we find, Kenyon avers, are “works centrally concerned with the practice of inquiry. When it comes to finding guidance, the dialogues look foremost to the act of inquiry itself: the fact that we can inquire at all tells us various things about ourselves.” The direction has shifted: what might it look like to view Augustine’s dialogues, and the nature of dialoguing in general, in terms of pedagogy and not in terms of content, as journeys of self-discovery instead of didactic treatises?

So what is to be done? What might seem like an esoteric crisis in Augustinian scholarship suddenly reflects a crisis about how we think, and how that thinking might give rise to a whole host of other predicaments. In which case, perhaps the resolution of one can aid us in resolving the other. In Augustine’s case, Kenyon argues that we should approach him in a holistic way and cease strip-mining his work for this or that argument or literary trope. We should especially not get bogged down in attempts to historically recreate Augustine’s psyche, but turn to the “overarching arguments and rhetorical strategy instead of individual passages” and “prefer interpretations that make sense of a text as a whole.” What we find, Kenyon avers, are “works centrally concerned with the practice of inquiry. When it comes to finding guidance, the dialogues look foremost to the act of inquiry itself: the fact that we can inquire at all tells us various things about ourselves.” The direction has shifted: what might it look like to view Augustine’s dialogues, and the nature of dialoguing in general, in terms of pedagogy and not in terms of content, as journeys of self-discovery instead of didactic treatises? In the middle of the 1420s, a Dominican friar painted an altarpiece for his convent, San Domenico in Fiesole, Florence, showing the Christian story of the Annunciation. Fra Giovanni, now known as Fra Angelico, was a professional artist who had opted for monastic life largely for the freedom it gave him to paint. The altarpiece, recently restored by the Prado Museum, Madrid, where it has resided since the nineteenth century, hangs at the centre of an exhibition at the museum showing how Angelico took this freedom and created a new type of painting.

In the middle of the 1420s, a Dominican friar painted an altarpiece for his convent, San Domenico in Fiesole, Florence, showing the Christian story of the Annunciation. Fra Giovanni, now known as Fra Angelico, was a professional artist who had opted for monastic life largely for the freedom it gave him to paint. The altarpiece, recently restored by the Prado Museum, Madrid, where it has resided since the nineteenth century, hangs at the centre of an exhibition at the museum showing how Angelico took this freedom and created a new type of painting. Someone else gets more quality time with your spouse, your kids, and your friends than you do. Like most people, you probably enjoy just about an hour, while your new rivals are taking a whopping 2 hours and 15 minutes each day. But save your jealousy. Your rivals are tremendously charming, and you have probably fallen for them as well.

Someone else gets more quality time with your spouse, your kids, and your friends than you do. Like most people, you probably enjoy just about an hour, while your new rivals are taking a whopping 2 hours and 15 minutes each day. But save your jealousy. Your rivals are tremendously charming, and you have probably fallen for them as well.