https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ihEmTlWm3N8

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ihEmTlWm3N8

bodies of agate. † Draw close the bones of this biddable metal:

………. chalice & ingot, gilt saints on cypress planks,

Agamemnon’s mask unearthed. Sulfur & salt: the alchemist’s

………. scarred hands. Think men upon their knees

before the riverbed for that Black Hills silt, that sluice

………. long girdled in the zigzag crack. O

that lucre. The worshipful company’s murderous guilds—

………. It’s too late now to look away from that bright flame,

too late to take the value back from filigree

………. or sacred blade, ransom-gilded Seric, idol,

from hidden trove or gently beaten fleece. South

………. of Ulaanbaatar cranes decorate the skyline.

In the Congo children work the pit shifts. Mercury & silica

………. will grace the margins of each living membrane’s

tender stem & inch of lymph. All flesh thus tempered,

………. thus fixed in the mine’s dark mouth.

Ûdwr. Meaning divine water.

………. Physika kai mystica: the secret things.

Our guide in Potosí lighting his cigar with dynamite:

………. “No se preocupe, trabajo par Sendero Luminoso!” Hands

cupping the bright flame. Tracing the halo.

………. The hoards turned up by English plowmen, amulets

in shafts along the overpass. Shields beaten thin

………. & dropped unearthly to your brokerage screen, leverage

on the scale of equity. Percolated, according to Theophilus,

………. from vinegar, red copper, human blood & ash of basilisk.

by Amy Beeder

†Ezra Pound, “The Alchemist”

Alyssa Battistoni in Dissent:

Alyssa Battistoni in Dissent:

What if the global ruling class was intentionally destroying the climate? Think about it: educated in the world’s most expensive institutions, they must understand what climate change means. They might understand its implications so well, in fact, that they have set out to make sure they are protected from it at the expense of everyone else. Having lost faith in the long-promised world of prosperity, and recognizing that the planet cannot support all of us, elites have deregulated the economy and dismantled the welfare state while lavishly funding the denial of climate change. And wasn’t it for these elites that Trump withdrew from the Paris accords, however much he gestured to the citizens of Pittsburgh?

This is the opening argument of Bruno Latour’s new book Down to Earth, which for those familiar with his work may come as a surprise. Latour, one of the most cited and celebrated academics in the world, is known not for his radical politics but for his theories of how scientific knowledge is made—theories sometimes charged with undermining faith in science itself. So you might expect him to investigate the nuts and bolts of climate science or perhaps to defend himself against the accusation that he has opened Pandora’s box and let post-truth out. (He has, in fact, written about both of these things.) But Latour is not interested in talking about climate science any longer. Of course we know climate change is happening, of course we know it is bad. Instead he is interested in how these facts are received, why they are accepted—or not—and, ultimately, in how we should face them.

More here.

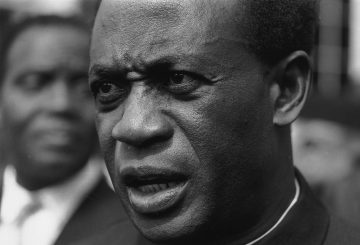

Sam Broadway in Jacobin:

In June, at an easy-to-miss two-story house with chipping white paint in Accra’s Asylum Down neighborhood, the Convention People’s Party (CPP) — Ghana’s oldest political party and the party founded by radical Pan-Africanist Kwame Nkrumah — celebrated its seventieth anniversary. Despite the presence of the Winneba Youth Choir and a large cake decorated in the party’s red, white, and green, a greater number of the white plastic folding chairs arranged under the guest tent remained empty rather than filled. The honored guests sitting on stage and the media workers roaming across the view likely outnumbered the guests by two-to-one.

Elder CPP apparatchiks and former party members gave speeches to a mostly absent crowd. Despite there being few ears to hear it, a single theme emerged: the need for the party of Nkrumah and its long-separated factions to reunite and support a single candidate in the approaching presidential elections.

Reunification may be the smallest of the challenges facing the party that still boasts Nkrumah’s cockerel as its symbol, in a country where the political imagination has been crippled by neoliberalism, where the two establishment parties compete primarily for who is the least corrupt and has the best slogans, and where political allegiance is fluid to nonexistent. Meanwhile, the parties the CPP hopes to reunite have maintained as much electoral significance as they have cohesion.

More here.

Lea Ypi in The New Statesman:

Lea Ypi in The New Statesman:

Shortly before his death last month, the radical intellectual Immanuel Wallerstein wrote a tentative prognosis of our current predicament. There is, he said, a “50-50 chance that we’ll make it to transformatory change, but only 50-50.”

“What those who will be alive in the future can do is to struggle with themselves so this change may be a real one,” he added in the commentary that was published on his personal blog.

Wallerstein died a few weeks later at the age of 88, in New York, the same city where he was born. The social theorist was perhaps best known for his account of society known as “world systems analysis”, a vision for how economic relations shape the development of legal, political and social institutions over time.

“I have indicated in the past that I thought the crucial struggle was a class struggle, using class in a very broadly defined sense,” he explained in the commentary. Wallerstein dedicated his life to this idea of “class struggle”, both in theory – he taught sociology at Columbia University, then SUNY Binghamton and finally Yale – but also in practice. During his travels in Ghana, Nigeria and Tanzania, Wallerstein witnessed first-hand peoples’ struggles for decolonisation, and anticipated how these political events would shape the development of African countries long after they were granted formal independence.

Bahar Gholipour in the Atlantic:

The death of free will began with thousands of finger taps. In 1964, two German scientists monitored the electrical activity of a dozen people’s brains. Each day for several months, volunteers came into the scientists’ lab at the University of Freiburg to get wires fixed to their scalp from a showerhead-like contraption overhead. The participants sat in a chair, tucked neatly in a metal tollbooth, with only one task: to flex a finger on their right hand at whatever irregular intervals pleased them, over and over, up to 500 times a visit.

The purpose of this experiment was to search for signals in the participants’ brains that preceded each finger tap. At the time, researchers knew how to measure brain activity that occurred in response to events out in the world—when a person hears a song, for instance, or looks at a photograph—but no one had figured out how to isolate the signs of someone’s brain actually initiating an action.

The experiment’s results came in squiggly, dotted lines, a representation of changing brain waves. In the milliseconds leading up to the finger taps, the lines showed an almost undetectably faint uptick: a wave that rose for about a second, like a drumroll of firing neurons, then ended in an abrupt crash. This flurry of neuronal activity, which the scientists called the Bereitschaftspotential, or readiness potential, was like a gift of infinitesimal time travel. For the first time, they could see the brain readying itself to create a voluntary movement.

More here.

Kriston Capps at The Atlantic:

Taken as a whole, Johnston’s career shows how neuroatypical artists usually remain on the margins of the music industry, even when the scene reveres them. When Mary Lou Lord, Beck, and other alt-rockers rerecorded his songs, their versions reached far wider audiences. Despite his brush with broader appeal, Johnston never achieved commercial success. Half his recorded catalog was committed to cassette, and the other albums were published by a string of small labels. Johnston reached his artistic zenith in the 2000s, with a tribute album featuring covers by Vic Chesnutt, Tom Waits, Death Cab for Cutie, and others.

But by the time his drawings made it into the 2006 biennial at the Whitney Museum of American Art, Johnston himself had mostly dropped off the map. Atlantic Records, the only major label to represent him, had let him go in 1996 after his debut album, Fun, proved to be a flop. He intermittently produced other recordings until 2012; while he endured hospitalizations all his life, in more recent years, they became frequent.

more here.

Kathryn Hughes at The Guardian:

When Vanessa Bell painted her sister, Virginia Woolf, in 1912 she didn’t give her eyes, although she did supply her with knitting needles and what looks like the beginnings of a reddish-pink scarf huddled in her lap. Woolf, it transpires, was far from being the only member of the Bloomsbury group who liked to spend her downtime plaining and purling. Younger brother Adrian had recently taken up the craft and, by the outbreak of war two years later, Lytton Strachey was busy “knitting mufflers for our soldier and sailor lads”, thrilling to the thought of the tender male bodies he might be warming with his busy fingers. As for Woolf’s novels, they are stuffed with women plying their pins. One academic has totted them up, and discovered that in her fictions there are more females who knit than write.

When Vanessa Bell painted her sister, Virginia Woolf, in 1912 she didn’t give her eyes, although she did supply her with knitting needles and what looks like the beginnings of a reddish-pink scarf huddled in her lap. Woolf, it transpires, was far from being the only member of the Bloomsbury group who liked to spend her downtime plaining and purling. Younger brother Adrian had recently taken up the craft and, by the outbreak of war two years later, Lytton Strachey was busy “knitting mufflers for our soldier and sailor lads”, thrilling to the thought of the tender male bodies he might be warming with his busy fingers. As for Woolf’s novels, they are stuffed with women plying their pins. One academic has totted them up, and discovered that in her fictions there are more females who knit than write.

Like all north Atlantic communities, Britain has depended for millennia on wool as a source of warmth and wealth, and Esther Rutter follows this thread by travelling around the sheepier parts of Britain, from Shetland to Guernsey and Norfolk to Monmouth.

more here.

Alissa Quart at the NYRB:

In the poetry and the albums, Berman’s poetic voice or his plaintive baritone insists that another truth is out there, a source of black humor: there were no jobs to be had, we had graduated into a recession, we would eternally be unpaid interns; if we were female, we faced endless harassment—without the language to describe, let alone protest, it; and many vulnerable people in our midst were overdoing it on anti-depressants, Ritalin, or Jim Beam. Berman struggled with it all: crack and Fentanyl and serious depression. “In 1984,” he wrote in one of his most memorable lyrics, “I was hospitalized for approaching perfection.” But he seemed to succeed in making his personal demons not an aberration, but something woven into and speaking for the experience of a generation.

His songs for Silver Jews had as their underpinning this sour, low-stakes refusal of the smugness and falsehoods around us, many which were political in nature. It was a pickled rejection of the upbeat mainstream.

more here.

Once she had a seamless mind.

Clouds rolled into her thinking

like opposites attracting. And hitching.

There was that openness of beginning.

Those crisp little white cockle shells. And then

that low fog. Spreading around

like when once you could touch time without rules or referees,

like when you used to dance alone with your eyes closed

serenading crazy in your room late, doors shut, the music on fire,

and you moved around in there, bumping the walls

like salmon swarming and flopping up the ladder.

Just that. Somehow just

to be seamless that way. Fiercely in the free.

Clouding in open fog.

by Linda E. Chown

from Numéro Cinq

Vol VIII, 2017

Snigdha Poonam in MIL:

When he’s doing his dance, Israil Ansari looks like a tornado. Keeping his feet pinned to the ground, he bends his elbows and knees and moves his arms and legs from side to side at such a high speed that his body and immediate surroundings dissolve into a blur. It’s a dance that divides opinion. His fans describe him as a “unique talent” and “the world’s eighth wonder”. He has more than 2m followers on TikTok, the video-sharing app that made his name. But his detractors don’t hold back: “I can’t bear to watch this”, “someone take this guy to a hospital”, “give us a break, bro”. Ansari says he is happy as long as people are watching. “Fifty percent of it is love, fifty percent of it is hate. I will take both.” Naturally, he prefers the love, although it can get a bit much. In Mumbai people stop him in the street. They ask for a selfie, then they ask him to do the dance. He always obliges, but when he’s in a hurry he wears a cap to avoid being ambushed. Without it, Ansari can be spotted a mile off because of his hair, which is almost as crazy as his dance. It’s currently green at the front and blond at the back, although it won’t be for long. He likes to dye it to match his clothes. “In one month I have changed my hair colour 27 times. No one else has done that in the world.”

When he’s doing his dance, Israil Ansari looks like a tornado. Keeping his feet pinned to the ground, he bends his elbows and knees and moves his arms and legs from side to side at such a high speed that his body and immediate surroundings dissolve into a blur. It’s a dance that divides opinion. His fans describe him as a “unique talent” and “the world’s eighth wonder”. He has more than 2m followers on TikTok, the video-sharing app that made his name. But his detractors don’t hold back: “I can’t bear to watch this”, “someone take this guy to a hospital”, “give us a break, bro”. Ansari says he is happy as long as people are watching. “Fifty percent of it is love, fifty percent of it is hate. I will take both.” Naturally, he prefers the love, although it can get a bit much. In Mumbai people stop him in the street. They ask for a selfie, then they ask him to do the dance. He always obliges, but when he’s in a hurry he wears a cap to avoid being ambushed. Without it, Ansari can be spotted a mile off because of his hair, which is almost as crazy as his dance. It’s currently green at the front and blond at the back, although it won’t be for long. He likes to dye it to match his clothes. “In one month I have changed my hair colour 27 times. No one else has done that in the world.”

Ansari is 19 and comes from a village in Uttar Pradesh in northern India, one of the poorest parts of the country. Until recently, he lived with his parents, grandparents and 11 siblings. His family couldn’t afford to keep him in school over the age of ten, so he dropped out and started working at a hardware store, supplementing his income with odd jobs, like painting houses or tiling. In 2017 he was at a wedding when a friend with a smartphone showed him TikTok, whose users post short, lo-fi videos of themselves doing just about anything: lip-syncing to pop music, conducting make-up tutorials, standing on their head. He was sold. “People were just expressing themselves. I thought: I could do that as well.”

He asked his brother, who works in a factory in Gujarat, to send him a smartphone. Then he started experimenting with TikTok. He made a few videos of himself joking around but failed to get much traction. Then one day in May 2018 he was walking through paddy fields listening to Bollywood tunes on his phone when a song featuring the actor Shah Rukh Khan began to play. He describes how, possessed by the music, he started to dance in a way no one had ever danced before: “This dance was just not there. Not in Bollywood films, not in the music videos. I brought it to the market,” he says, sweeping his hair back from his face.

More here.

Laura Miller in The New York Times:

Stephen King’s protagonists have been hunted by all sorts of malevolent beings, from the demonic clown of “It” to the fiendish cowboy Randall Flagg in “The Stand.” But as scary as those supernatural bad guys can be, King’s most unsettling antagonists are human-size: the blocked writer sliding into delusions of grandeur and domestic violence, the fan possessed to the point of madness by someone else’s fiction, the bullied teenager made homicidal by the cruelty of her peers. We can see something of ourselves in these characters, and recognize in them our own capacity for evil. King’s latest novel, “The Institute,” belongs to this second category, and is as consummately honed and enthralling as the very best of his work. It has no ghosts, no vampires, no metamorphosing diabolical entities or invaders from other dimensions intent on tormenting innocent children. Innocent children are tormented in “The Institute,” but the people who do it are much like you and me.

Stephen King’s protagonists have been hunted by all sorts of malevolent beings, from the demonic clown of “It” to the fiendish cowboy Randall Flagg in “The Stand.” But as scary as those supernatural bad guys can be, King’s most unsettling antagonists are human-size: the blocked writer sliding into delusions of grandeur and domestic violence, the fan possessed to the point of madness by someone else’s fiction, the bullied teenager made homicidal by the cruelty of her peers. We can see something of ourselves in these characters, and recognize in them our own capacity for evil. King’s latest novel, “The Institute,” belongs to this second category, and is as consummately honed and enthralling as the very best of his work. It has no ghosts, no vampires, no metamorphosing diabolical entities or invaders from other dimensions intent on tormenting innocent children. Innocent children are tormented in “The Institute,” but the people who do it are much like you and me.

The novel opens with Tim Jamieson, an ex-cop (he was forced to resign from the Sarasota, Fla., police department after an episode he describes as a “Rube Goldberg” bungle) wandering north to South Carolina, hitchhiking and working odd jobs until he lands in DuPray, a podunk railway depot town with shuttered storefronts and a rundown motel. He takes a gig as a sort of semi-official night patrolman and finds he rather likes the place. That’s the last we’ll hear from him for quite a while, but these first 40 pages of “The Institute” — low-key and relaxed, an unaffected and genially convincing depiction of a certain uncelebrated walk of life — demonstrate how engaging King’s fiction can be even without an underlying low whine of dread.

More here.

Tanaïs at the SAADA website:

TANAÏS: Your work inhabits multitudinous Black – Muslim – Desi Diasporic connections, and as a producer, looping and sampling feel like an homage to Hiphop / Atlanta / Outkast. And yet, there is a resounding indie / synth rock / dream pop quality to the music, which slowly crescendos into what I hear as qawwali influences in your music. It feels like a syncretic, stateless, borderless sound.

HUMEYSHA: There’s a line from Grandmaster Flash about how hip-hop pioneers would “adopt” from the history of music by taking a few seconds of a groove, playing it on repeat, and finding a rhythm for audiences to dance to. Whether it’s with a few bars from a qawwali recording or my guitar experiments, I think I’ve always been in love with the sampling technique for how it embodies a very contemporary way we make our selves. To intimately know histories of music, dig through the archives, and identify passages that loop seamlessly, without clicks or pops where the endings match the beginning—it’s a tool of infinite possibility despite being constrained by a strict sense of time and bound up with material. People like you and I assert how we are similarly not fixed, static identities bound only by our inheritance or biology; what matters is what we do with it, by remixing past to remake ourselves anew. I am not just where I come from or where I reside, but also all I’ve invested in. And as a musician that’s why I draw on sounds from all the places I lived in to voice new ones that feel more like home.

HUMEYSHA: There’s a line from Grandmaster Flash about how hip-hop pioneers would “adopt” from the history of music by taking a few seconds of a groove, playing it on repeat, and finding a rhythm for audiences to dance to. Whether it’s with a few bars from a qawwali recording or my guitar experiments, I think I’ve always been in love with the sampling technique for how it embodies a very contemporary way we make our selves. To intimately know histories of music, dig through the archives, and identify passages that loop seamlessly, without clicks or pops where the endings match the beginning—it’s a tool of infinite possibility despite being constrained by a strict sense of time and bound up with material. People like you and I assert how we are similarly not fixed, static identities bound only by our inheritance or biology; what matters is what we do with it, by remixing past to remake ourselves anew. I am not just where I come from or where I reside, but also all I’ve invested in. And as a musician that’s why I draw on sounds from all the places I lived in to voice new ones that feel more like home.

More here.

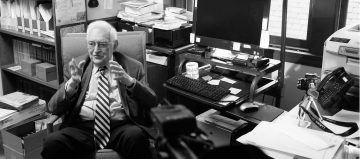

Sarah Poole in University of Virginia Magazine:

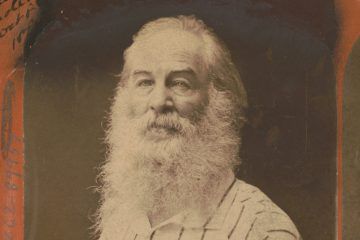

Fredson Bowers didn’t know what he would find when he began digging into the disordered stack of 230 loose pages—all from 19th-century Walt Whitman manuscripts—that landed on his desk in 1951.

Fredson Bowers didn’t know what he would find when he began digging into the disordered stack of 230 loose pages—all from 19th-century Walt Whitman manuscripts—that landed on his desk in 1951.

But for Bowers, a revered UVA English professor, the papers formed a massive puzzle waiting to be fit together. They were an “opportunity for literary detective work … that was of the highest interest to attempt,” he wrote in 1959.

Bowers solved the puzzle—or part of it—when he discovered within that pile the unpublished original sequence for 12 poems, together called “Live Oak, with Moss,” that were distributed throughout a section of the 1860 edition of Leaves of Grass.

The revelation of that sequence, illuminated by Bowers’ painstaking research, opened a door to insights that would change the way scholars looked at Whitman.

Unlike most of his work, “Live Oak” addresses themes of love. Scholars believe Whitman wrote the sequence after a relationship with a man named Fred Vaughan.

More here.

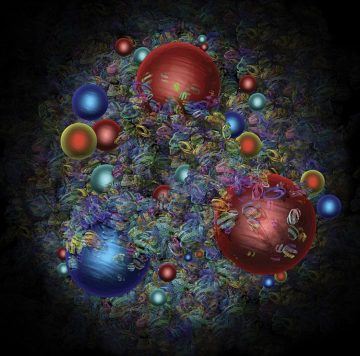

Natalie Wolchover in Quanta:

In 2010, physicists in Germany reported that they had made an exceptionally precise measurement of the size of the proton, the positively charged building block of atomic nuclei. The result was very puzzling.

In 2010, physicists in Germany reported that they had made an exceptionally precise measurement of the size of the proton, the positively charged building block of atomic nuclei. The result was very puzzling.

Randolf Pohl of the Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics and collaborators had measured the proton using special hydrogen atoms in which the electron that normally orbits the proton was replaced by a muon, a particle that’s identical to the electron but 207 times heavier. Pohl’s team found the muon-orbited protons to be 0.84 femtometers in radius — 4% smaller than those in regular hydrogen, according to the average of more than two dozen earlier measurements.

If the discrepancy was real, meaning protons really shrink in the presence of muons, this would imply unknown physical interactions between protons and muons — a fundamental discovery. Hundreds of papers speculating about the possibility have been written in the near-decade since.

But hopes that the “proton radius puzzle” would upend particle physics and reveal new laws of nature have now been dashed by a new measurement reported on Sept. 6 in Science.

More here.

Marshall Steinbaum in Boston Review:

Binyamin Appelbaum’s new book has lived up to its controversial billing, particularly among its subjects. The book condemns the role the economics profession has played in breeding inequality, and holds economists to account for the resulting backlash of xenophobic white nationalism. When the New York Times published an excerpt, the reaction was sadly predictable: How dare he suggest that economists don’t care about inequality? It is only because of economists that we know that inequality has risen. How dare he point out that economists have occupied a privileged position in public life? These behind-the-scenes advisors very close to power should not be implicated in whatever unsatisfactory state of economic affairs exists today.

Binyamin Appelbaum’s new book has lived up to its controversial billing, particularly among its subjects. The book condemns the role the economics profession has played in breeding inequality, and holds economists to account for the resulting backlash of xenophobic white nationalism. When the New York Times published an excerpt, the reaction was sadly predictable: How dare he suggest that economists don’t care about inequality? It is only because of economists that we know that inequality has risen. How dare he point out that economists have occupied a privileged position in public life? These behind-the-scenes advisors very close to power should not be implicated in whatever unsatisfactory state of economic affairs exists today.

This is exactly the privileged carping I feared would arise from the so-called “empirical revolution” in economics. Empiricism has manifestly changed the content of economics scholarship in recent years. On the one hand, economists seem to say, better and more enlightened scholarship now excuses past wrongs, and on the other, economists aren’t really responsible for anything that may have been wrong to begin with. As a result, the rhetoric of empiricism has been weaponized to paper over the field’s culpability and to permit retrograde tendencies to remain in place even as what counts as scholarship has changed.

More here.