by Anitra Pavlico

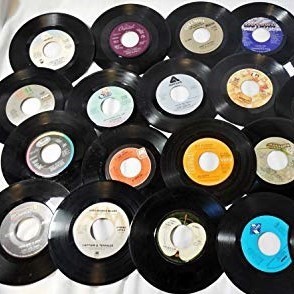

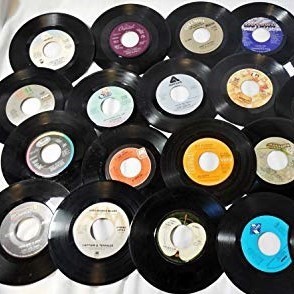

What has happened to music? To the joy of cozying up with your records, tapes, or CDs and your music source, whether it was a boom box, or stereo with faux-wood speakers taller than a small child, or Walkman? It used to be simple to figure out where to buy music and how to listen to it. You went to the local record store, and then you brought it home and absconded to your bedroom, where you cranked your new purchase as loud as you could before your parents knocked on the door and told you to turn it down. There was a spatial aspect to music, as the music store was obviously circumscribed in space, with different sections for different tastes. Listening also usually took place in an intimate setting, layered like a palimpsest with memories of years past. Well before five-disc (and then 100-plus-disc) CD changers, we listened to one album at a time, and usually with the songs in the same order that the artist or the producer intended. It was a form of communion, however illusory, with the musician. There were also visual and tactile elements, as you had something to hold in your hands and pore over–liner notes, album credits, lyrics, glossy pictures of the band members. Did anyone ever vote to relinquish these sensory companions to the music-listening experience?

I did not have access to the ultimate in high fidelity as a kid, and I remember practically gluing my ear to my Sony Dream Machine clock radio’s speaker. When my parents bought me my first “boom box” they managed to find one with only one speaker. It hardly boomed, but it was still more than sufficient. In my mind’s ear, even these devices had much better sound quality than the digital music we have come to rely on. At the source, at least, the sound was fuller, less broken down or compressed into heartless bits and bytes. We did also have a lot of vinyl, not because we were hipsters, but because it was the 1970s.

I can’t pretend that it always makes a difference, today’s lesser sound quality. It was a trade-off that didn’t trouble me for years as I joined the rest of the world in celebrating the fact that virtually my entire music collection could fit on an iPod that I could carry around with me. As years go by, and you simply lose the memory of what music used to sound like, you don’t realize that convenience has supplanted most of the other elements of the experience of listening to music. Read more »

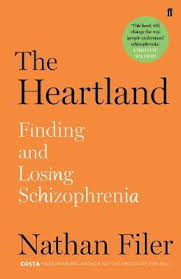

Madness is deep-rooted in the human imagination. The mad are unreachable, unfathomable, alarmingly other. They unsettle us. Yet we also romanticise madness. Great poetry and art spring from transcendent states at the edge of sanity, don’t they? And falling in love is a kind of madness, a stumbling into a dream world of irrationality and delusion. The lunatic, the lover and the poet are of imagination all compact. One line of thought is that madness is the price Homo sapiens has paid for the jewel of human consciousness. Perhaps it is.

Madness is deep-rooted in the human imagination. The mad are unreachable, unfathomable, alarmingly other. They unsettle us. Yet we also romanticise madness. Great poetry and art spring from transcendent states at the edge of sanity, don’t they? And falling in love is a kind of madness, a stumbling into a dream world of irrationality and delusion. The lunatic, the lover and the poet are of imagination all compact. One line of thought is that madness is the price Homo sapiens has paid for the jewel of human consciousness. Perhaps it is.

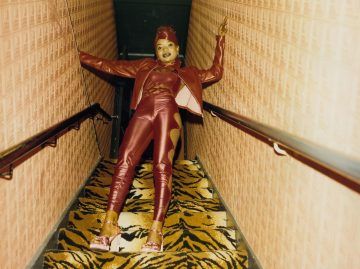

There is so much sound, movement, and energy in Liz Johnson Artur’s first solo museum show, “Dusha,” at the Brooklyn Museum, that walking through the galleries feels like attending a party at a local Pan-African community center. The exhibit showcases Artur’s “Black Balloon Archive,” which consists of images of the global African diaspora captured in the course of decades. Here are two boys spinning each other on the sidewalk, surrounded by a crowd of onlookers. Nearby is Brother Michael, in a black suit and white tie, selling Nation of Islam newspapers. A group of women show off their matching head wraps, and precocious schoolgirls relax outside a classroom. A man wearing Ankara prints and sunglasses mugs for the camera. All that is missing is the line for jollof and the music of Fela Kuti.

There is so much sound, movement, and energy in Liz Johnson Artur’s first solo museum show, “Dusha,” at the Brooklyn Museum, that walking through the galleries feels like attending a party at a local Pan-African community center. The exhibit showcases Artur’s “Black Balloon Archive,” which consists of images of the global African diaspora captured in the course of decades. Here are two boys spinning each other on the sidewalk, surrounded by a crowd of onlookers. Nearby is Brother Michael, in a black suit and white tie, selling Nation of Islam newspapers. A group of women show off their matching head wraps, and precocious schoolgirls relax outside a classroom. A man wearing Ankara prints and sunglasses mugs for the camera. All that is missing is the line for jollof and the music of Fela Kuti. With its gold-striped spine, crimson endpapers and silky leaves, My Seditious Heart is a handsome edition of previously published essays by Booker-winning writer

With its gold-striped spine, crimson endpapers and silky leaves, My Seditious Heart is a handsome edition of previously published essays by Booker-winning writer  Precision medicine flips the script on conventional medicine, which typically offers blanket recommendations and prescribes treatments designed to help more people than they harm but that might not work for you. The approach recognizes that we each possess distinct molecular characteristics, and they have an outsize impact on our health. Around the world, researchers are creating precision tools unimaginable just a decade ago: superfast DNA sequencing, tissue engineering, cellular reprogramming, gene editing, and more. The science and technology soon will make it feasible to predict your risk of cancer, heart disease, and countless other ailments years before you get sick. The work also offers prospects—tantalizing or unnerving, depending on your point of view—for altering genes in embryos and eliminating inherited diseases.

Precision medicine flips the script on conventional medicine, which typically offers blanket recommendations and prescribes treatments designed to help more people than they harm but that might not work for you. The approach recognizes that we each possess distinct molecular characteristics, and they have an outsize impact on our health. Around the world, researchers are creating precision tools unimaginable just a decade ago: superfast DNA sequencing, tissue engineering, cellular reprogramming, gene editing, and more. The science and technology soon will make it feasible to predict your risk of cancer, heart disease, and countless other ailments years before you get sick. The work also offers prospects—tantalizing or unnerving, depending on your point of view—for altering genes in embryos and eliminating inherited diseases.

Racing down a German autobahn at impossible speeds is like running past a smorgasbord when you don’t have time to eat. Exit signs fly by, pointing to delicious, iconic destinations that whet the appetite but that one has no time for: Hameln, Wittenberg, Quedlinburg, Eisenach, Erfurt, Altenburg, Jena, Weimar, Dessau—markers of histories whose tentacles reach into the present in ways that belie their sleepy status on the map. You suppress the urge to slow down and take the off-ramp instead of moving right along to a big-city destination You opt to remain on the asphalt treadmill with arrival anxiety, telling yourself that one day you will take the time to explore all this, just not right now.

Racing down a German autobahn at impossible speeds is like running past a smorgasbord when you don’t have time to eat. Exit signs fly by, pointing to delicious, iconic destinations that whet the appetite but that one has no time for: Hameln, Wittenberg, Quedlinburg, Eisenach, Erfurt, Altenburg, Jena, Weimar, Dessau—markers of histories whose tentacles reach into the present in ways that belie their sleepy status on the map. You suppress the urge to slow down and take the off-ramp instead of moving right along to a big-city destination You opt to remain on the asphalt treadmill with arrival anxiety, telling yourself that one day you will take the time to explore all this, just not right now. Two weeks ago the 9th US Circuit Court heard

Two weeks ago the 9th US Circuit Court heard  President Trump is now calling for expanding the death penalty so it would apply to drug dealers and those who kill police officers, with an expedited trial and quick execution. A majority of Americans (56 percent,

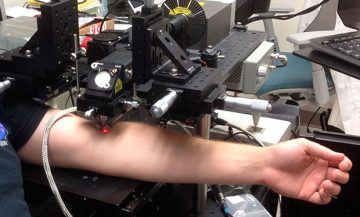

President Trump is now calling for expanding the death penalty so it would apply to drug dealers and those who kill police officers, with an expedited trial and quick execution. A majority of Americans (56 percent, Tumor cells that spread cancer via the bloodstream face a new foe: a laser beam, shined from outside the skin, that finds and kills these metastatic little demons on the spot.

Tumor cells that spread cancer via the bloodstream face a new foe: a laser beam, shined from outside the skin, that finds and kills these metastatic little demons on the spot. On July

On July Across the continent, many had anticipated further gains for far-right parties that masquerade in populism but spit raw racism. Thankfully, the so-called populist surge has been halted for the moment.

Across the continent, many had anticipated further gains for far-right parties that masquerade in populism but spit raw racism. Thankfully, the so-called populist surge has been halted for the moment.