Jason Zinoman in The New York Times:

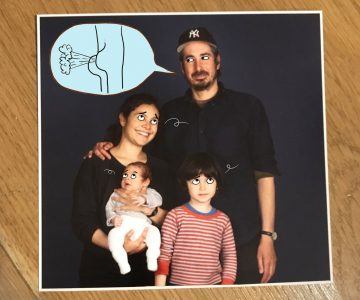

I’m a comedy critic, so being a dad can seem like an occupational hazard. It may be professional suicide to admit, but since having children, I often find myself making lame puns as well as poop jokes. In subway stations, I have been known to silently mouth words to my daughters when a loud train goes by until the noise quiets and I add: “ … and that’s the secret to life.” Look, I’m not proud. The demise of a dad’s sense of humor begins in early parenthood while workshopping jokes in front of babies, tiny philistines who think peekaboo is a hilarious bit of misdirection. It isn’t long before these drooling rubes turn into trash-talking toddlers and fall in love with the scatological. Like so many lazy comics, we parents pander. If jokes work, they stay in the set. Gradually, we become hooked on cheap laughs. Some of us even delude ourselves into thinking we are actually funny.

I’m a comedy critic, so being a dad can seem like an occupational hazard. It may be professional suicide to admit, but since having children, I often find myself making lame puns as well as poop jokes. In subway stations, I have been known to silently mouth words to my daughters when a loud train goes by until the noise quiets and I add: “ … and that’s the secret to life.” Look, I’m not proud. The demise of a dad’s sense of humor begins in early parenthood while workshopping jokes in front of babies, tiny philistines who think peekaboo is a hilarious bit of misdirection. It isn’t long before these drooling rubes turn into trash-talking toddlers and fall in love with the scatological. Like so many lazy comics, we parents pander. If jokes work, they stay in the set. Gradually, we become hooked on cheap laughs. Some of us even delude ourselves into thinking we are actually funny.

…The most common dad joke relies on puns. (“What has two butts and kills people? An assassin.”) To redeem them, you needn’t point out that Shakespeare used such jokes.

…Say what you will about a joke like, “What do you call someone with no body and just a nose? Nobody knows,” but it doesn’t age.

More here.

Alice Whittenburg in 3:AM Magazine:

Alice Whittenburg in 3:AM Magazine: Evgeny Morozov in The Guardian:

Evgeny Morozov in The Guardian: Rana Foroohar in the FT:

Rana Foroohar in the FT: Nick Hanauer in The Atlantic:

Nick Hanauer in The Atlantic: Suketu Mehta traveled the same route five times. As a child, he settled with his family, originally from Gujarat in India, in the United States. As an adult, he returned to India, where he lived in Mumbai (Bombay) for two and a half years and wrote a book about the city. Titled Maximum City: Bombay Lost and Found and published in 2004, it was a highly acclaimed work that I can’t recommend enough. Mehta later returned to the United States, only to retrace his footsteps years later – but this time in his reminisces and feelings – in a new book, where he returns to the memories of his family voyage, to the story of how they, like so many others, moved to America, the promised land of generations of migrants. The second part of the title of Mehta’s new work says it all — This Land is Our Land: An Immigrant’s Manifesto. It is a powerful defense of people’s right to migrate, a song of praise for multiculturalism, and a strong critique of Washington’s policies toward immigrants and refugees under President Donald Trump. The author took pains to travel and collect various stories of migration – he took these pains quite literally, as a large part of the book is a cataloging of sorrows that people shared with him. Focusing mainly on the United States as a destination country, he provides statistics and cases to show where and how migration policies are failing. Mehta wrestles with the exorbitant fears of the “Other,” with the myth that the influx of migrants will sweep the country away.

Suketu Mehta traveled the same route five times. As a child, he settled with his family, originally from Gujarat in India, in the United States. As an adult, he returned to India, where he lived in Mumbai (Bombay) for two and a half years and wrote a book about the city. Titled Maximum City: Bombay Lost and Found and published in 2004, it was a highly acclaimed work that I can’t recommend enough. Mehta later returned to the United States, only to retrace his footsteps years later – but this time in his reminisces and feelings – in a new book, where he returns to the memories of his family voyage, to the story of how they, like so many others, moved to America, the promised land of generations of migrants. The second part of the title of Mehta’s new work says it all — This Land is Our Land: An Immigrant’s Manifesto. It is a powerful defense of people’s right to migrate, a song of praise for multiculturalism, and a strong critique of Washington’s policies toward immigrants and refugees under President Donald Trump. The author took pains to travel and collect various stories of migration – he took these pains quite literally, as a large part of the book is a cataloging of sorrows that people shared with him. Focusing mainly on the United States as a destination country, he provides statistics and cases to show where and how migration policies are failing. Mehta wrestles with the exorbitant fears of the “Other,” with the myth that the influx of migrants will sweep the country away. To Kill a Mockingbird is a drama of white nobility in a white context, in which educated white people struggle decorously for black rights against the dangerous unreasonableness of uneducated white people. In one of the many passages in which Lee uses Atticus’ conversations with his children, Jem and Scout (the narrator of the novel) as Socratic expositions of the problems with the 1930s justice system, Jem asks this question: “why don’t people like us and Miss Maudie ever sit on juries? You never see anybody from Maycomb on a jury—they all come from out in the woods.” Jem is philosophically ready to abolish juries altogether. Atticus doesn’t put up much of an argument for why juries are necessary, saying only, “You’re rather hard on us, son” — meaning, presumably, that democracy has its good points too. Instead, Atticus offers a different solution: “I think there might be a better way. Change the law. Change it so that only judges have the power of fixing the penalty in capital cases.”

To Kill a Mockingbird is a drama of white nobility in a white context, in which educated white people struggle decorously for black rights against the dangerous unreasonableness of uneducated white people. In one of the many passages in which Lee uses Atticus’ conversations with his children, Jem and Scout (the narrator of the novel) as Socratic expositions of the problems with the 1930s justice system, Jem asks this question: “why don’t people like us and Miss Maudie ever sit on juries? You never see anybody from Maycomb on a jury—they all come from out in the woods.” Jem is philosophically ready to abolish juries altogether. Atticus doesn’t put up much of an argument for why juries are necessary, saying only, “You’re rather hard on us, son” — meaning, presumably, that democracy has its good points too. Instead, Atticus offers a different solution: “I think there might be a better way. Change the law. Change it so that only judges have the power of fixing the penalty in capital cases.” I first read “

I first read “ In a new study, Stanford psychologists examined why some people respond differently to an upsetting situation and learned that people’s motivations play an important role in how they react. Their study found that when a person wanted to stay calm, they remained relatively unfazed by angry people, but if they wanted to feel angry, then they were highly influenced by angry people. The researchers also discovered that people who wanted to feel angry also got more emotional when they learned that other people were just as upset as they were, according to the results from a series of laboratory experiments the researchers conducted.

In a new study, Stanford psychologists examined why some people respond differently to an upsetting situation and learned that people’s motivations play an important role in how they react. Their study found that when a person wanted to stay calm, they remained relatively unfazed by angry people, but if they wanted to feel angry, then they were highly influenced by angry people. The researchers also discovered that people who wanted to feel angry also got more emotional when they learned that other people were just as upset as they were, according to the results from a series of laboratory experiments the researchers conducted. Let’s go around the room and introduce ourselves.

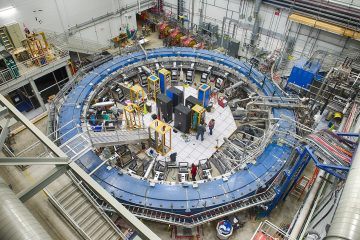

Let’s go around the room and introduce ourselves. Physicists count 25 elementary particles that, for all we presently know, cannot be divided any further. They collect these particles and their interactions in what is called the Standard Model of particle physics.

Physicists count 25 elementary particles that, for all we presently know, cannot be divided any further. They collect these particles and their interactions in what is called the Standard Model of particle physics. In the spring of 1938, the Mexican press reported on the perils faced by Sigmund Freud in post-Anschluss Austria: The Gestapo had raided the offices of the Psychoanalytic Publishing House, searched the apartment at Berggasse 19, and briefly detained his daughter Anna. Freud himself — once reluctant to consider emigration — made up his mind to leave Vienna, but his decision seemed to come too late: obtaining an exit visa had become a nearly impossible ordeal for Austrian Jews. Freud would have been trapped in Vienna had it not been for a group of powerful friends who launched a full-scale diplomatic campaign on his behalf: William Bullitt, the American ambassador to France; Ernest Jones, who lobbied British Members of Parliament; and Princess Marie Bonaparte, who was in direct communication with President Roosevelt himself.

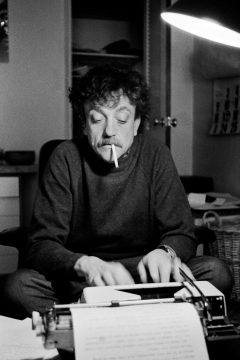

In the spring of 1938, the Mexican press reported on the perils faced by Sigmund Freud in post-Anschluss Austria: The Gestapo had raided the offices of the Psychoanalytic Publishing House, searched the apartment at Berggasse 19, and briefly detained his daughter Anna. Freud himself — once reluctant to consider emigration — made up his mind to leave Vienna, but his decision seemed to come too late: obtaining an exit visa had become a nearly impossible ordeal for Austrian Jews. Freud would have been trapped in Vienna had it not been for a group of powerful friends who launched a full-scale diplomatic campaign on his behalf: William Bullitt, the American ambassador to France; Ernest Jones, who lobbied British Members of Parliament; and Princess Marie Bonaparte, who was in direct communication with President Roosevelt himself. The discarded ending of Camera Obscura, transcribed and translated here for the first time, sheds light on

The discarded ending of Camera Obscura, transcribed and translated here for the first time, sheds light on  Sylvia Plath was hungry for new experiences when she returned to Smith College as a junior in the fall of 1952 and wrote “Mary Ventura and the Ninth Kingdom.” Over the summer she won a $500 prize in the Mademoiselle fiction writing contest with her short story “Sunday at the Mintons’.” When this psychological story was later featured in the Fall 1952 issue of the Smith Review, a literary journal Plath helped revive, it earned her the respect of Mary Ellen Chase, a successful author of novels, critical writings, and commentaries on Biblical literature who became Plath’s trusted mentor. In recommending Plath for graduate school, Chase wrote that in her twenty-seven years as an English professor at Smith she had not known a more gifted “literary artist.” Professor Chase contributed the first article to the Fall 1952 issue of the Smith Review—a definition of Smith College: “the one thing we are afraid of is apathy and indifference toward learning and toward life.” In “Mary Ventura and the Ninth Kingdom,” Plath reinforces Chase’s criticism of complacency when Mary’s traveling companion remarks sadly that others on the train “are so blasé, so apathetic that they don’t even care about where they are going.

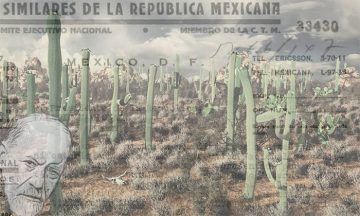

Sylvia Plath was hungry for new experiences when she returned to Smith College as a junior in the fall of 1952 and wrote “Mary Ventura and the Ninth Kingdom.” Over the summer she won a $500 prize in the Mademoiselle fiction writing contest with her short story “Sunday at the Mintons’.” When this psychological story was later featured in the Fall 1952 issue of the Smith Review, a literary journal Plath helped revive, it earned her the respect of Mary Ellen Chase, a successful author of novels, critical writings, and commentaries on Biblical literature who became Plath’s trusted mentor. In recommending Plath for graduate school, Chase wrote that in her twenty-seven years as an English professor at Smith she had not known a more gifted “literary artist.” Professor Chase contributed the first article to the Fall 1952 issue of the Smith Review—a definition of Smith College: “the one thing we are afraid of is apathy and indifference toward learning and toward life.” In “Mary Ventura and the Ninth Kingdom,” Plath reinforces Chase’s criticism of complacency when Mary’s traveling companion remarks sadly that others on the train “are so blasé, so apathetic that they don’t even care about where they are going. Although Chávez—born on this date in 1899—received his earliest musical training from his brother, and though he did study for a time with the composer Manuel Ponce, he largely taught himself how to write music by studying the scores of others. Early on, he became interested in furthering the cause of Mexican classical music, while reimagining its possibilities in the 20th century. Should it draw heavily from folk styles? How Mexican should it be? How avant-garde? Perhaps most crucial of all: How could a composer forge a style out of so many various elements: native Indian music, the plainsong brought by the conquistadores, the peasant dances of the countryside, the ballad-like corridos—to say nothing of the European symphonic and operatic literature? These questions must have been swimming in his head when, at the age of 21, Chávez traveled to Austria, Germany, and France. In Paris, he befriended Paul Dukas (composer of The Sorcerer’s Apprentice), who instructed the young man to incorporate vernacular Mexican music into his pieces, pointing to the example of Manuel de Falla, who had been doing similar things in Spain with Spanish music.

Although Chávez—born on this date in 1899—received his earliest musical training from his brother, and though he did study for a time with the composer Manuel Ponce, he largely taught himself how to write music by studying the scores of others. Early on, he became interested in furthering the cause of Mexican classical music, while reimagining its possibilities in the 20th century. Should it draw heavily from folk styles? How Mexican should it be? How avant-garde? Perhaps most crucial of all: How could a composer forge a style out of so many various elements: native Indian music, the plainsong brought by the conquistadores, the peasant dances of the countryside, the ballad-like corridos—to say nothing of the European symphonic and operatic literature? These questions must have been swimming in his head when, at the age of 21, Chávez traveled to Austria, Germany, and France. In Paris, he befriended Paul Dukas (composer of The Sorcerer’s Apprentice), who instructed the young man to incorporate vernacular Mexican music into his pieces, pointing to the example of Manuel de Falla, who had been doing similar things in Spain with Spanish music. Thirty years ago socialism was dead and buried. This was not an illusion or a temporary hiccup, a point all the more important to emphasize up front in light of its recent revival in this country and around the world. There was no reason this resurrection had to happen; no law of nature or history compelled it. To understand why it did is to unlock a door, behind which lies something like the truth of our age.

Thirty years ago socialism was dead and buried. This was not an illusion or a temporary hiccup, a point all the more important to emphasize up front in light of its recent revival in this country and around the world. There was no reason this resurrection had to happen; no law of nature or history compelled it. To understand why it did is to unlock a door, behind which lies something like the truth of our age.