Sissela Bok in The American Scholar:

Conscience: The Origins of Moral Intuition by Patricia S. Churchland

The War For Kindness: Building Empathy in a Fractured World by Jamil Zaki

These two new books give lucid, stimulating accounts of recent discoveries in neuroscience and psychology. Both authors aim to challenge antiquated views of the brain and human behavior. In so doing, they help us think through perennial debates about the sources of morality and the degree to which we inherit or can enhance traits like empathy. Both are careful to evaluate the cogency of the research they cite, noting when it remains inconclusive or unpersuasive. Jamil Zaki, a professor of psychology at Stanford, who also directs its Social Neuroscience Laboratory, usefully includes an appendix summarizing the evidence for the findings he cites and giving them a 1 to 5 rating, from weaker to stronger. Oddly, however, neither book mentions, much less rates, possible moral problems with some of the research, whether by neuroscientists injecting substances into the brains of rats or monkeys or by social scientists subjecting students to deceptive scenarios.

These two new books give lucid, stimulating accounts of recent discoveries in neuroscience and psychology. Both authors aim to challenge antiquated views of the brain and human behavior. In so doing, they help us think through perennial debates about the sources of morality and the degree to which we inherit or can enhance traits like empathy. Both are careful to evaluate the cogency of the research they cite, noting when it remains inconclusive or unpersuasive. Jamil Zaki, a professor of psychology at Stanford, who also directs its Social Neuroscience Laboratory, usefully includes an appendix summarizing the evidence for the findings he cites and giving them a 1 to 5 rating, from weaker to stronger. Oddly, however, neither book mentions, much less rates, possible moral problems with some of the research, whether by neuroscientists injecting substances into the brains of rats or monkeys or by social scientists subjecting students to deceptive scenarios.

Early on, Churchland, professor emerita of philosophy at the University of California–San Diego, sets forth a working formulation of conscience as “an individual’s judgment about what is morally right or wrong, typically, but not always, reflecting some standard of a group to which the individual feels attached.” Later, she states that conscience “is a brain construct rooted in our neural circuitry, not a theological entity thoughtfully parked in us by a divine being.” The intervening chapters show in fascinating detail the path leading from the first to the second formulation. They explain the role of the cortex for mammals, culminating in the unusually large one of humans, and argue that an attachment to mothers—and in some cases to fathers, kin, and friends—is fundamental to social behavior and in turn to moral behavior. Human moral responses are therefore rooted in the cortex, supported by more ancient structures, such as basal ganglia and neurochemicals such as dopamine, sex hormones, and the neurohormones of oxytocin and vasopressin. Studies show how these factors combine, specifying their different roles, as for oxytocin in strengthening social bonds. When it comes to psychopaths, however—people with no moral compass who lack feelings of guilt or remorse and exhibit no empathy toward people they have injured—it has, so far, proved harder to locate specific brain abnormalities. The same is true of persons exhibiting self-destructive moral behavior, known as scrupulosity.

More here.

Impossible Foods seems to have created heme out of a belief that it’s the visual stimulation of blood oozing from a burger that gives it an addictive taste. What Specht’s book reveals about beef, though, is that its extraordinary success has always had little to do with its taste and everything to do with its ubiquity, increasing cheapness, and cultural status. Red Meat Republic doesn’t bring the reader up to date with innovations in plant-based beef, but it doesn’t have to. By laying down the political and economic history of beef production and culture in the United States, he demonstrates why the tech-meat industry isn’t spending time, money, or marketing dollars on chicken and goat.

Impossible Foods seems to have created heme out of a belief that it’s the visual stimulation of blood oozing from a burger that gives it an addictive taste. What Specht’s book reveals about beef, though, is that its extraordinary success has always had little to do with its taste and everything to do with its ubiquity, increasing cheapness, and cultural status. Red Meat Republic doesn’t bring the reader up to date with innovations in plant-based beef, but it doesn’t have to. By laying down the political and economic history of beef production and culture in the United States, he demonstrates why the tech-meat industry isn’t spending time, money, or marketing dollars on chicken and goat.

Formally, aesthetically, “Tithonus” is a remarkable work. But it is made even more remarkable by its language. Trapped in his decaying body as day knits itself around him, Tithonus notices all. At first, the “bleak shapes of last efforts of / the night”. A little later, “bodiless black lace woods” peopled with songbirds asking one another “is it light is it light”. Later still the “whisper of a grasshopper scraping / back and forth as if working at rust”. The features of dawn concatenate and though Tithonus has seen them all before (and will see them all again), he cannot help but testify to the beauty of breaking day, with its “peach-pale air” and its rustling solitudes. At one point, a lone snail “pokes out of sleep too feelingly / as if a heart had been tinned and / opened”. It is a weird image, ghoulish and frightful, but a moving one.

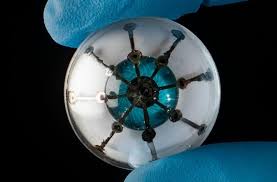

Formally, aesthetically, “Tithonus” is a remarkable work. But it is made even more remarkable by its language. Trapped in his decaying body as day knits itself around him, Tithonus notices all. At first, the “bleak shapes of last efforts of / the night”. A little later, “bodiless black lace woods” peopled with songbirds asking one another “is it light is it light”. Later still the “whisper of a grasshopper scraping / back and forth as if working at rust”. The features of dawn concatenate and though Tithonus has seen them all before (and will see them all again), he cannot help but testify to the beauty of breaking day, with its “peach-pale air” and its rustling solitudes. At one point, a lone snail “pokes out of sleep too feelingly / as if a heart had been tinned and / opened”. It is a weird image, ghoulish and frightful, but a moving one. The innovations I describe here—many of which are still in early stages—are impressive in their own right. But I also appreciate them for enabling the shift away from our traditional compartmentalized health care toward a model of “connected health.” We have the opportunity now to connect the dots—to move beyond institutions delivering episodic and reactive care, primarily after disease has developed, into an era of continuous and proactive care designed to get ahead of disease. Think of it: ever present, analytics-enabled, real-time, individualized attention to our health and well-being. Not just to treat disease, but increasingly, to prevent it.

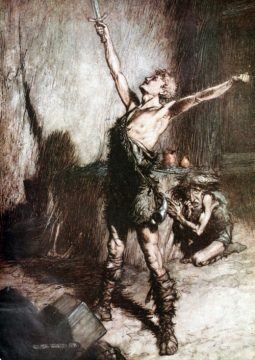

The innovations I describe here—many of which are still in early stages—are impressive in their own right. But I also appreciate them for enabling the shift away from our traditional compartmentalized health care toward a model of “connected health.” We have the opportunity now to connect the dots—to move beyond institutions delivering episodic and reactive care, primarily after disease has developed, into an era of continuous and proactive care designed to get ahead of disease. Think of it: ever present, analytics-enabled, real-time, individualized attention to our health and well-being. Not just to treat disease, but increasingly, to prevent it. Music can have a decisive influence in a person’s life and in a nation’s history. Were it not for a brief passage in the second volume of Ian Kershaw’s biography of Hitler, I would never have learned of the direct connection between Wagner’s Siegfried and the first crucial victory of Franco’s army during the uprising that set off the Spanish Civil War. On July 25, 1936, as Kershaw recounts, Adolf Hitler attended a production of Siegfried in Bayreuth, which brought him to the state of exaltation that Wagner’s music had always caused in him from early youth. From the age of 17, to be precise, when he first heard Rienzi in Linz—as August Kubizek, friend, countryman and companion during his early years in his native city and then in Vienna, would reverently record years later. On that day in 1906, a young Hitler left the opera house in a fevered state of musical and patriotic excitement, rapt in a sense of kinship with the figure of the Roman tribune who in the fourteenth century tried to revive the glories of imperial Rome, only to meet, in Wagner’s opera, an heroic, glorious end at the hands of his betrayers. In June of 1936, exactly thirty years later, Hitler’s deranged dream was being fulfilled.

Music can have a decisive influence in a person’s life and in a nation’s history. Were it not for a brief passage in the second volume of Ian Kershaw’s biography of Hitler, I would never have learned of the direct connection between Wagner’s Siegfried and the first crucial victory of Franco’s army during the uprising that set off the Spanish Civil War. On July 25, 1936, as Kershaw recounts, Adolf Hitler attended a production of Siegfried in Bayreuth, which brought him to the state of exaltation that Wagner’s music had always caused in him from early youth. From the age of 17, to be precise, when he first heard Rienzi in Linz—as August Kubizek, friend, countryman and companion during his early years in his native city and then in Vienna, would reverently record years later. On that day in 1906, a young Hitler left the opera house in a fevered state of musical and patriotic excitement, rapt in a sense of kinship with the figure of the Roman tribune who in the fourteenth century tried to revive the glories of imperial Rome, only to meet, in Wagner’s opera, an heroic, glorious end at the hands of his betrayers. In June of 1936, exactly thirty years later, Hitler’s deranged dream was being fulfilled.

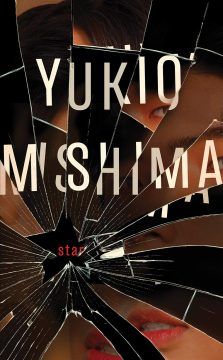

IT SEEMS BOTH the great comedy and the great tragedy of Yukio Mishima’s life that hardly any of his work’s plots live up to his death. While anything but a wallflower, Mishima didn’t have the topsy-turvy life of a Daniel Defoe or a Herman Melville — he was neither jailed and pilloried nor on the hunt for roly-poly whales. But when it comes to spectacular deaths among the writers of the world, Mishima is top tier.

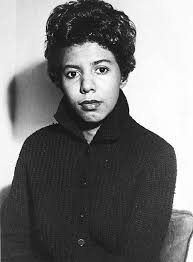

IT SEEMS BOTH the great comedy and the great tragedy of Yukio Mishima’s life that hardly any of his work’s plots live up to his death. While anything but a wallflower, Mishima didn’t have the topsy-turvy life of a Daniel Defoe or a Herman Melville — he was neither jailed and pilloried nor on the hunt for roly-poly whales. But when it comes to spectacular deaths among the writers of the world, Mishima is top tier. When Lorraine Vivian Hansberry died on January 12, 1965, her play The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window was at the end of a three-month run at Broadway’s Longacre Theatre. It was the second play written by a black woman to appear on Broadway. The first was her groundbreaking drama A Raisin in the Sun. Ntozake Shange’s for colored girls who have considered suicide when the rainbow is enuf, the third, opened in 1976. Remembrances of Shange published last year, after her death, called for colored girls “the second play by an African American woman” to have a Broadway run. In writing my own remembrance of Shange, I nearly made the same mistake. We are prone to myopia when we remember, and it can make inconvenient details difficult to decipher. Jewell Handy Gresham-Nemiroff, in charge of Hansberry’s estate for fourteen years, wrote that Hansberry is “not really credited, to the extent deserved, with being Mother of the modern black drama.” The scholar Margaret Wilkerson called Hansberry one of the “major literary catalysts” of the Black Arts Movement. Both are true, yet The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window, which Hansberry worked on feverishly during hospital stays at the end of her life, is not a black drama.

When Lorraine Vivian Hansberry died on January 12, 1965, her play The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window was at the end of a three-month run at Broadway’s Longacre Theatre. It was the second play written by a black woman to appear on Broadway. The first was her groundbreaking drama A Raisin in the Sun. Ntozake Shange’s for colored girls who have considered suicide when the rainbow is enuf, the third, opened in 1976. Remembrances of Shange published last year, after her death, called for colored girls “the second play by an African American woman” to have a Broadway run. In writing my own remembrance of Shange, I nearly made the same mistake. We are prone to myopia when we remember, and it can make inconvenient details difficult to decipher. Jewell Handy Gresham-Nemiroff, in charge of Hansberry’s estate for fourteen years, wrote that Hansberry is “not really credited, to the extent deserved, with being Mother of the modern black drama.” The scholar Margaret Wilkerson called Hansberry one of the “major literary catalysts” of the Black Arts Movement. Both are true, yet The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window, which Hansberry worked on feverishly during hospital stays at the end of her life, is not a black drama. A

A  Thinking about the risk-reward of air travel can help us think about how to solve the most perplexing problem of our time—the clean energy dilemma. All the known solutions to producing clean power have risks. So how do we evaluate the risk/reward of each possibility? How do we decide which ones to pursue? Being human, our evaluation of risk is hampered by our tendency to focus on the sensational single event instead of the broader picture. When looking at accidents or “disasters,” we also tend to ignore the reward we were getting from whatever it was that failed. For example, if one were to focus only on crashes, deaths, and disasters, we would quickly conclude that air travel is deadly and must be seriously curtailed. Yet in spite of the danger, people clearly think the reward of air travel is worth taking the risk. Moreover, if one steps back, looks at the full picture, and evaluates the danger of air travel compared to other methods, it becomes clear that putting a halt to air travel would result in more, not fewer, deaths. The relative risk of air travel is lower than other travel options.

Thinking about the risk-reward of air travel can help us think about how to solve the most perplexing problem of our time—the clean energy dilemma. All the known solutions to producing clean power have risks. So how do we evaluate the risk/reward of each possibility? How do we decide which ones to pursue? Being human, our evaluation of risk is hampered by our tendency to focus on the sensational single event instead of the broader picture. When looking at accidents or “disasters,” we also tend to ignore the reward we were getting from whatever it was that failed. For example, if one were to focus only on crashes, deaths, and disasters, we would quickly conclude that air travel is deadly and must be seriously curtailed. Yet in spite of the danger, people clearly think the reward of air travel is worth taking the risk. Moreover, if one steps back, looks at the full picture, and evaluates the danger of air travel compared to other methods, it becomes clear that putting a halt to air travel would result in more, not fewer, deaths. The relative risk of air travel is lower than other travel options. Poet, writer and musician Joy Harjo — a member of the Muscogee Creek Nation — often draws on Native American stories, languages and myths. But she says that she’s not self-consciously trying to bring that material into her work. If anything, it’s the other way around.

Poet, writer and musician Joy Harjo — a member of the Muscogee Creek Nation — often draws on Native American stories, languages and myths. But she says that she’s not self-consciously trying to bring that material into her work. If anything, it’s the other way around. These two new books give lucid, stimulating accounts of recent discoveries in neuroscience and psychology. Both authors aim to challenge antiquated views of the brain and human behavior. In so doing, they help us think through perennial debates about the sources of morality and the degree to which we inherit or can enhance traits like empathy. Both are careful to evaluate the cogency of the research they cite, noting when it remains inconclusive or unpersuasive. Jamil Zaki, a professor of psychology at Stanford, who also directs its Social Neuroscience Laboratory, usefully includes an appendix summarizing the evidence for the findings he cites and giving them a 1 to 5 rating, from weaker to stronger. Oddly, however, neither book mentions, much less rates, possible moral problems with some of the research, whether by neuroscientists injecting substances into the brains of rats or monkeys or by social scientists subjecting students to deceptive scenarios.

These two new books give lucid, stimulating accounts of recent discoveries in neuroscience and psychology. Both authors aim to challenge antiquated views of the brain and human behavior. In so doing, they help us think through perennial debates about the sources of morality and the degree to which we inherit or can enhance traits like empathy. Both are careful to evaluate the cogency of the research they cite, noting when it remains inconclusive or unpersuasive. Jamil Zaki, a professor of psychology at Stanford, who also directs its Social Neuroscience Laboratory, usefully includes an appendix summarizing the evidence for the findings he cites and giving them a 1 to 5 rating, from weaker to stronger. Oddly, however, neither book mentions, much less rates, possible moral problems with some of the research, whether by neuroscientists injecting substances into the brains of rats or monkeys or by social scientists subjecting students to deceptive scenarios. It is easy to make fun of the Aristotelian idea that humans are rational animals. In fact, a bit too easy. Just look at the politicians we elect. Not so rational. Or look at all the well-demonstrated biases of decision-making, from confirmation bias to availability bias. Thinking of humans as deeply irrational has an illustrious history, from Francis Bacon through Nietzsche to Oscar Wilde, who, as so often, came up with the bon mot that sums it all up: “Man is a rational animal who always loses his temper when he is called upon to act in accordance with the dictates of reason.”

It is easy to make fun of the Aristotelian idea that humans are rational animals. In fact, a bit too easy. Just look at the politicians we elect. Not so rational. Or look at all the well-demonstrated biases of decision-making, from confirmation bias to availability bias. Thinking of humans as deeply irrational has an illustrious history, from Francis Bacon through Nietzsche to Oscar Wilde, who, as so often, came up with the bon mot that sums it all up: “Man is a rational animal who always loses his temper when he is called upon to act in accordance with the dictates of reason.” Is “discussion” really so wonderful? Does “communication” actually exist? What if I were to deny that it does?

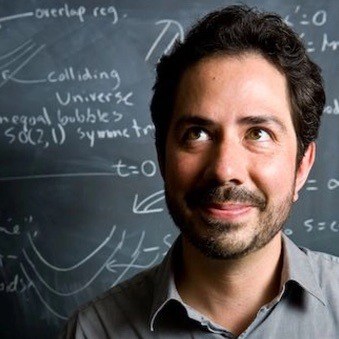

Is “discussion” really so wonderful? Does “communication” actually exist? What if I were to deny that it does? Cosmologists have a standard set of puzzles they think about: the nature of dark matter and dark energy, whether there was a period of inflation, the evolution of structure, and so on. But there are also even deeper questions, having to do with why there is a universe at all, and why the early universe had low entropy, that most working cosmologists don’t address. Today’s guest, Anthony Aguirre, is an exception. We talk about these deep issues, and how tackling them might lead to a very different way of thinking about our universe. At the end there’s an entertaining detour into AI and existential risk.

Cosmologists have a standard set of puzzles they think about: the nature of dark matter and dark energy, whether there was a period of inflation, the evolution of structure, and so on. But there are also even deeper questions, having to do with why there is a universe at all, and why the early universe had low entropy, that most working cosmologists don’t address. Today’s guest, Anthony Aguirre, is an exception. We talk about these deep issues, and how tackling them might lead to a very different way of thinking about our universe. At the end there’s an entertaining detour into AI and existential risk. Debates about political correctness on college campuses can be extremely frustrating. On one side you have those, like New York magazine’s Jonathan Chait, who

Debates about political correctness on college campuses can be extremely frustrating. On one side you have those, like New York magazine’s Jonathan Chait, who  In his new book, “Irrationality: A History of the Dark Side of Reason” philosopher Justin Smith presents a fascinating narrative that reveals the ways in which the pursuit of rationality often leads to an explosion of irrationality. Smith, a professor of the history and philosophy of science at the University of Paris, acknowledges that we are living in an era when nothing seems to make sense. Populism is on the rise, pseudoscience is still around and there is no shortage of of conspiracy theories. Smith discusses the core of the problem that the rational gives birth to the irrational and vice versa in an endless cycle, and any effort to permanently set things in order sooner or later ends in an explosion of unreason.

In his new book, “Irrationality: A History of the Dark Side of Reason” philosopher Justin Smith presents a fascinating narrative that reveals the ways in which the pursuit of rationality often leads to an explosion of irrationality. Smith, a professor of the history and philosophy of science at the University of Paris, acknowledges that we are living in an era when nothing seems to make sense. Populism is on the rise, pseudoscience is still around and there is no shortage of of conspiracy theories. Smith discusses the core of the problem that the rational gives birth to the irrational and vice versa in an endless cycle, and any effort to permanently set things in order sooner or later ends in an explosion of unreason. He notes that despite the fact logic and reason are well understood, methods and practises that were supposed to have been setup to counter irrationality, ended up mired in the very problem that they were meant to solve, and that is irrationality.

He notes that despite the fact logic and reason are well understood, methods and practises that were supposed to have been setup to counter irrationality, ended up mired in the very problem that they were meant to solve, and that is irrationality. Simpson’s benevolent yet piercing approach to life is not far from how her art grasps us under the guise of beautiful images of models from magazine spreads. Her unassuming warmth and determination to always look into my eyes during our conversation melts the breeze emanating from her paintings of mountainous ice chunks gloriously standing at remote corners of the world. She blows up images culled from science publications and prints them onto gessoed fiberglass, after adding occasional cutouts of text. Then, the surface is hers to paint into blue, horizontally or on the floor, letting the blues build serpentine paths on the surface. In the far corner of her spacious studio, blown up images of women pulled from Ebony and Jet magazine ads stare in convincing perfection. Arguably her most extensively know works, her collages of women from vintage magazine ads have over the decades evolved into bridges between America’s past and present histories of race and visibility.

Simpson’s benevolent yet piercing approach to life is not far from how her art grasps us under the guise of beautiful images of models from magazine spreads. Her unassuming warmth and determination to always look into my eyes during our conversation melts the breeze emanating from her paintings of mountainous ice chunks gloriously standing at remote corners of the world. She blows up images culled from science publications and prints them onto gessoed fiberglass, after adding occasional cutouts of text. Then, the surface is hers to paint into blue, horizontally or on the floor, letting the blues build serpentine paths on the surface. In the far corner of her spacious studio, blown up images of women pulled from Ebony and Jet magazine ads stare in convincing perfection. Arguably her most extensively know works, her collages of women from vintage magazine ads have over the decades evolved into bridges between America’s past and present histories of race and visibility.