Eric Bulson at the TLS:

In May 1975, Michel Foucault watched Venus rise over Zabriskie Point while Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Gesang der Jünglinge (Song of the Youths) blared from the speakers of a nearby tape recorder. Just a few hours earlier he had ingested LSD for the first time and was in the process of undergoing what he saw as “one of the most important experiences” of his life. And he wasn’t alone. Two newly acquired companions had brought Foucault to Death Valley for this carefully choreographed trip complete with a soundtrack, some marijuana to jumpstart the effects, and cold drinks to combat the dry mouth. It was all spurred on by the hope that Foucault’s visit to “the Valley of Death”, as he called it, would elicit “gnomic utterances of such power that he would unleash a veritable revolution in consciousness”.

In May 1975, Michel Foucault watched Venus rise over Zabriskie Point while Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Gesang der Jünglinge (Song of the Youths) blared from the speakers of a nearby tape recorder. Just a few hours earlier he had ingested LSD for the first time and was in the process of undergoing what he saw as “one of the most important experiences” of his life. And he wasn’t alone. Two newly acquired companions had brought Foucault to Death Valley for this carefully choreographed trip complete with a soundtrack, some marijuana to jumpstart the effects, and cold drinks to combat the dry mouth. It was all spurred on by the hope that Foucault’s visit to “the Valley of Death”, as he called it, would elicit “gnomic utterances of such power that he would unleash a veritable revolution in consciousness”.

For decades, the details of this trip have remained sketchy. The most extensive account appeared in James Miller’s 1993 biography, The Passion of Michel Foucault, but anyone following the footnotes would have realized that the specifics, the ones above included, were based almost entirely on the documentary evidence of a self-proclaimed disciple, Simeon Wade.

more here.

Scientists have created the world’s first living organism that has a fully synthetic and radically altered DNA code.

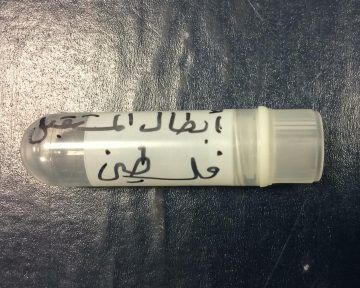

Scientists have created the world’s first living organism that has a fully synthetic and radically altered DNA code. Ashraf had been gone for more than a decade when he and Fat’hiya first heard about a fertility clinic in Ramallah that had begun helping the wives of Palestinian prisoners become pregnant with sperm smuggled out of Israeli jails. (Israeli prisoners are permitted conjugal visits; Palestinians are not.) The couple discussed it, Fat’hiya says, but neither of them was convinced it was a good idea.

Ashraf had been gone for more than a decade when he and Fat’hiya first heard about a fertility clinic in Ramallah that had begun helping the wives of Palestinian prisoners become pregnant with sperm smuggled out of Israeli jails. (Israeli prisoners are permitted conjugal visits; Palestinians are not.) The couple discussed it, Fat’hiya says, but neither of them was convinced it was a good idea.

In the first large-scale analysis of cancer gene fusions, which result from the merging of two previously separate genes, researchers at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, EMBL-EBI, Open Targets, GSK and their collaborators have used CRISPR to uncover which gene fusions are critical for the growth of cancer cells. The team also identified a new gene fusion that presents a novel drug target for multiple cancers, including brain and ovarian cancers. The results, published today (16 May) in Nature Communications, give more certainty for the use of specific

In the first large-scale analysis of cancer gene fusions, which result from the merging of two previously separate genes, researchers at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, EMBL-EBI, Open Targets, GSK and their collaborators have used CRISPR to uncover which gene fusions are critical for the growth of cancer cells. The team also identified a new gene fusion that presents a novel drug target for multiple cancers, including brain and ovarian cancers. The results, published today (16 May) in Nature Communications, give more certainty for the use of specific  Somewhat surprisingly, nature not only requires disorder but thrives on it. Planets, stars, life, even the direction of time all depend on disorder. And we human beings as well. Especially if, along with disorder, we group together such concepts as randomness, novelty, spontaneity, free will and unpredictability. We might put all of these ideas in the same psychic basket. Within the oppositional category of order, we can gather together notions such as systems, law, reason, rationality, pattern, predictability. While the different clusters of concepts are not mirror images of one another, like twilight and dawn, they have much in common.

Somewhat surprisingly, nature not only requires disorder but thrives on it. Planets, stars, life, even the direction of time all depend on disorder. And we human beings as well. Especially if, along with disorder, we group together such concepts as randomness, novelty, spontaneity, free will and unpredictability. We might put all of these ideas in the same psychic basket. Within the oppositional category of order, we can gather together notions such as systems, law, reason, rationality, pattern, predictability. While the different clusters of concepts are not mirror images of one another, like twilight and dawn, they have much in common. I’m going to go over a wide range of things that everyone will likely find something to disagree with. I want to start out by saying that I’m a materialist reductionist. As I talk, some people might get a little worried that I’m going off like Chalmers or something, but I’m not. I’m a materialist reductionist.

I’m going to go over a wide range of things that everyone will likely find something to disagree with. I want to start out by saying that I’m a materialist reductionist. As I talk, some people might get a little worried that I’m going off like Chalmers or something, but I’m not. I’m a materialist reductionist. I have been a professor at Harvard University for 34 years. In that time, the school has made some mistakes. But it has never so thoroughly embarrassed itself as it did this past weekend. At the center of the controversy is Ronald Sullivan, a law professor who ran afoul of student activists enraged that he was willing to represent Harvey Weinstein.

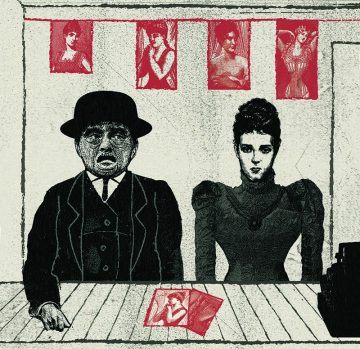

I have been a professor at Harvard University for 34 years. In that time, the school has made some mistakes. But it has never so thoroughly embarrassed itself as it did this past weekend. At the center of the controversy is Ronald Sullivan, a law professor who ran afoul of student activists enraged that he was willing to represent Harvey Weinstein. And it is here—at the level of physics—that the fates of the characters in The Secret Agent are truly decided: for they all—the criminal and the legitimate—run things too close, or simply let them fall. Conrad, surely, in his depiction of Verloc’s murder and its aftermath, surpassed all others—contemporary or otherwise—in his evocation of what it might be like to take a life, and the immediate psychic consequences for the killer: the complete and utter loneliness of Winnie Verloc after the murder is foreshadowed by this beautifully exact evocation of a psychic state, seen from within: “Her personality seemed to have been torn into two pieces, whose mental operations did not adjust themselves very well to each other.” A deracinated Polish aristocrat who tried to reinvent himself as a tweedy English country gentleman—the pseudonymous and multilingual Conrad knew all about being torn in pieces.

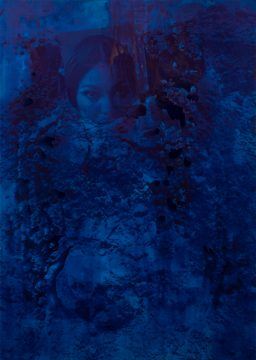

And it is here—at the level of physics—that the fates of the characters in The Secret Agent are truly decided: for they all—the criminal and the legitimate—run things too close, or simply let them fall. Conrad, surely, in his depiction of Verloc’s murder and its aftermath, surpassed all others—contemporary or otherwise—in his evocation of what it might be like to take a life, and the immediate psychic consequences for the killer: the complete and utter loneliness of Winnie Verloc after the murder is foreshadowed by this beautifully exact evocation of a psychic state, seen from within: “Her personality seemed to have been torn into two pieces, whose mental operations did not adjust themselves very well to each other.” A deracinated Polish aristocrat who tried to reinvent himself as a tweedy English country gentleman—the pseudonymous and multilingual Conrad knew all about being torn in pieces. The works in “Darkening,” a new exhibit of paintings by the artist Lorna Simpson, at Hauser & Wirth, are monumental panels that drown the viewer in blues—some shades so potent that they are black, purple. Using graduated saturations of ink-wash over gesso, Simpson builds landscapes and seascapes that recall J. M. W. Turner or Chinese shan shui compositions. But within these views of nature she plants artifacts of culture. Thin strips of what look like newspaper text are layered into a mountain in the painting “Blue Turned Temporal,” the meaning disintegrated. The heads and bodies of models from the pages of Ebony magazine are choked in inky waters. One day, not long ago, I lost myself staring into the series’ tallest work, “Specific Notation,” which, at twelve feet, threatens to reach the gallery’s ceiling. The lower two-thirds of the canvas feature circular stains that suggest underwater rock formations. Then, as if bursting from the mineral, the head of a woman appears suspended in the upper third of the frame, her face screwed into an expression of coy glowering. By the style of her hair, and by the manicuring of her eyebrows, we know that she is a figure of recent human history. But, in Simpson’s painting, frozen in the icy blue canvas, she seems eternal, outside of time.

The works in “Darkening,” a new exhibit of paintings by the artist Lorna Simpson, at Hauser & Wirth, are monumental panels that drown the viewer in blues—some shades so potent that they are black, purple. Using graduated saturations of ink-wash over gesso, Simpson builds landscapes and seascapes that recall J. M. W. Turner or Chinese shan shui compositions. But within these views of nature she plants artifacts of culture. Thin strips of what look like newspaper text are layered into a mountain in the painting “Blue Turned Temporal,” the meaning disintegrated. The heads and bodies of models from the pages of Ebony magazine are choked in inky waters. One day, not long ago, I lost myself staring into the series’ tallest work, “Specific Notation,” which, at twelve feet, threatens to reach the gallery’s ceiling. The lower two-thirds of the canvas feature circular stains that suggest underwater rock formations. Then, as if bursting from the mineral, the head of a woman appears suspended in the upper third of the frame, her face screwed into an expression of coy glowering. By the style of her hair, and by the manicuring of her eyebrows, we know that she is a figure of recent human history. But, in Simpson’s painting, frozen in the icy blue canvas, she seems eternal, outside of time. I

I In the summer of 1892 the poet

In the summer of 1892 the poet  Every mythology needs a good trickster, and there are few better than the Norse god Loki. He stirs trouble and insults other gods. He is elusive, anarchic and ambiguous. He is, in other words, the perfect namesake for a group of microbes — the Lokiarchaeota — that is rewriting a fundamental story about life’s early roots. These unruly microbes belong to a category of single-celled organisms called archaea, which resemble bacteria under a microscope but are as distinct from them in some respects as humans are. The Lokis, as they are sometimes known, were discovered by sequencing DNA from sea-floor muck collected near Greenland

Every mythology needs a good trickster, and there are few better than the Norse god Loki. He stirs trouble and insults other gods. He is elusive, anarchic and ambiguous. He is, in other words, the perfect namesake for a group of microbes — the Lokiarchaeota — that is rewriting a fundamental story about life’s early roots. These unruly microbes belong to a category of single-celled organisms called archaea, which resemble bacteria under a microscope but are as distinct from them in some respects as humans are. The Lokis, as they are sometimes known, were discovered by sequencing DNA from sea-floor muck collected near Greenland

Most of us have no trouble telling the difference between a robot and a living, feeling organism. Nevertheless, our brains often treat robots as if they were alive. We give them names, imagine that they have emotions and inner mental states, get mad at them when they do the wrong thing or feel bad for them when they seem to be in distress. Kate Darling is a research at the MIT Media Lab who specializes in social robotics, the interactions between humans and machines. We talk about why we cannot help but anthropomorphize even very non-human-appearing robots, and what that means for legal and social issues now and in the future, including robot companions and helpers in various forms.

Most of us have no trouble telling the difference between a robot and a living, feeling organism. Nevertheless, our brains often treat robots as if they were alive. We give them names, imagine that they have emotions and inner mental states, get mad at them when they do the wrong thing or feel bad for them when they seem to be in distress. Kate Darling is a research at the MIT Media Lab who specializes in social robotics, the interactions between humans and machines. We talk about why we cannot help but anthropomorphize even very non-human-appearing robots, and what that means for legal and social issues now and in the future, including robot companions and helpers in various forms.