Kwame Anthony Appiah in the New York Review of Books:

How enlightened was the Enlightenment? Not a few critics have seen it as profoundly benighted. For some, it was a seedbed for modern racism and imperialism; the light in the Enlightenment, one recent scholar has suggested, essentially meant “white.” Voltaire emphatically believed in the inherent inferiority of les Nègres, who belonged to a separate species, or at least breed, from Europeans—as different from Europeans, he said, as spaniels from greyhounds. Kant remarked, of something a Negro carpenter opined, that “the fact that he was black from head to toe was proof that what he said was stupid.” And David Hume wrote, in a notorious footnote, that he was “apt to suspect” that nonwhites were “naturally inferior to the whites,” devoid of arts and science and “ingenious manufactures.”

The more general critiques take up larger intellectual currents in the eighteenth century. The era’s systematic forays into physical anthropology and human classification laid the foundation for the noxious race science that emerged in the nineteenth century. So did the rise of materialism: it became harder to argue that our varying physical carapaces housed equivalent souls implanted by God. A heedless sense of universalism, in turn, might encourage the thought that the more advanced civilizations were merely lifting up those more backward when they conquered and colonized them.

The more general critiques take up larger intellectual currents in the eighteenth century. The era’s systematic forays into physical anthropology and human classification laid the foundation for the noxious race science that emerged in the nineteenth century. So did the rise of materialism: it became harder to argue that our varying physical carapaces housed equivalent souls implanted by God. A heedless sense of universalism, in turn, might encourage the thought that the more advanced civilizations were merely lifting up those more backward when they conquered and colonized them.

More here.

Feynman was born 100 years ago May 11. It’s an anniversary inspiring much celebration in the physics world. Feynman was one of the last great physicist celebrities, universally acknowledged as a genius who stood out even from other geniuses.

Feynman was born 100 years ago May 11. It’s an anniversary inspiring much celebration in the physics world. Feynman was one of the last great physicist celebrities, universally acknowledged as a genius who stood out even from other geniuses.

The title of this essay may sound redundant: aren’t all Stoics unemotional, making it their business to go through life with a stiff upper lip? Actually, no, and neither was Marcus, whose 1,898th birthday falls on April 26th of this year. It is true that he wrote in the Meditations, his personal philosophical diary: ‘When you have savouries and fine dishes set before you, you will gain an idea of their nature if you tell yourself that this is the corpse of a fish, and that the corpse of a bird or a pig; or again, that fine Falernian wine is merely grape-juice, and this purple robe some sheep’s wool dipped in the blood of a shellfish; and as for sexual intercourse, it is the friction of a piece of gut and, following a sort of convulsion, the expulsion of mucus.’ (VI.13)

The title of this essay may sound redundant: aren’t all Stoics unemotional, making it their business to go through life with a stiff upper lip? Actually, no, and neither was Marcus, whose 1,898th birthday falls on April 26th of this year. It is true that he wrote in the Meditations, his personal philosophical diary: ‘When you have savouries and fine dishes set before you, you will gain an idea of their nature if you tell yourself that this is the corpse of a fish, and that the corpse of a bird or a pig; or again, that fine Falernian wine is merely grape-juice, and this purple robe some sheep’s wool dipped in the blood of a shellfish; and as for sexual intercourse, it is the friction of a piece of gut and, following a sort of convulsion, the expulsion of mucus.’ (VI.13) Speakers recently flew in from around (or perhaps, across?) the earth for a three-day event held in Birmingham: the UK’s first ever public

Speakers recently flew in from around (or perhaps, across?) the earth for a three-day event held in Birmingham: the UK’s first ever public  Michael J. Barany in the LA Review of Books:

Michael J. Barany in the LA Review of Books: Dennis Overbye in the NYT:

Dennis Overbye in the NYT: Corey Robin in The New Yorker:

Corey Robin in The New Yorker: David A. Bell in Dissent:

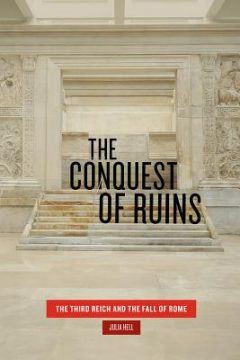

David A. Bell in Dissent: Empires are strange creatures. Obsessed with their own end-time, they enlist the help of the katechon—a form of political sovereignty that “delays or maintains the end of time”—to postpone the inevitable, and stretch out time before the end. The obsessive fear of decline and an active engagement with trying to delay the end of empire is something that links contemporary right-wing movements to Himmler’s, Spengler’s, and Friedrich Ratzel’s temporal understandings of the basis for the National Socialist empire. The difference between then and now is that Hitler’s “solution” to the racial diversity he diagnosed as one of the core problems contributing to the cyclicity of empires and their inevitable decline was the murder of those the National Socialist regime deemed to be barbarians.

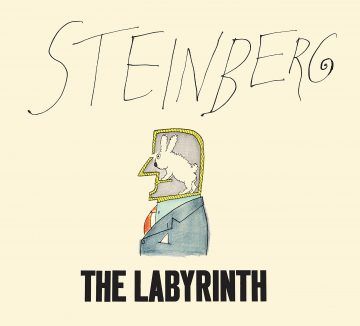

Empires are strange creatures. Obsessed with their own end-time, they enlist the help of the katechon—a form of political sovereignty that “delays or maintains the end of time”—to postpone the inevitable, and stretch out time before the end. The obsessive fear of decline and an active engagement with trying to delay the end of empire is something that links contemporary right-wing movements to Himmler’s, Spengler’s, and Friedrich Ratzel’s temporal understandings of the basis for the National Socialist empire. The difference between then and now is that Hitler’s “solution” to the racial diversity he diagnosed as one of the core problems contributing to the cyclicity of empires and their inevitable decline was the murder of those the National Socialist regime deemed to be barbarians. SAUL STEINBERG CALLED HIMSELF “a writer who draws.” Harold Rosenberg called him “a writer in pictures.” Critics compared him to Klee and Picasso, but reviews were just as likely to namedrop Joyce and Stendhal. He was friends with Nabokov as well as Saul Bellow, Primo Levi, William Gaddis, Donald Barthelme, John Hollander, Charles Simic, and Ian Frazier. Ulysseswas his favorite novel. Nabokov’s essay on Gogol was his guidebook.

SAUL STEINBERG CALLED HIMSELF “a writer who draws.” Harold Rosenberg called him “a writer in pictures.” Critics compared him to Klee and Picasso, but reviews were just as likely to namedrop Joyce and Stendhal. He was friends with Nabokov as well as Saul Bellow, Primo Levi, William Gaddis, Donald Barthelme, John Hollander, Charles Simic, and Ian Frazier. Ulysseswas his favorite novel. Nabokov’s essay on Gogol was his guidebook. S

S THE SIMULTANEOUS RELEASE

THE SIMULTANEOUS RELEASE