Over at The Hedgehog & the Fox, an interview with Rachel Sherman:

Over at The Hedgehog & the Fox, an interview with Rachel Sherman:

New School sociologist Rachel Sherman interviewed fifty affluent residents of New York (the most unequal city in the United States) to find out their attitudes to wealth. She writes of her sample:

“Most households had incomes of over $500,000 per year, assets of over $3 million, or both. About half earned over $1 million annually and/or had assets of over $8 million. The median household income of the sample was about $625,000, which is twelve times the New York City median of about $52,000. […] They worked or had worked in finance, law, real estate, advertising, academia, nonprofits, the arts, and fashion.”

What she discovered in her interviews is presented in her recent book, Uneasy Street, which is full of fascinating insights into what she calls “the anxieties of affluence”, the ongoing struggles her informants experience over how to combine being wealthy with feeling they possess moral worth. This often leads them to emphasize who they are as opposed to what they have. They also repeatedly highlight virtues normally associated with the middle class: hard work, modest consumption, a commitment to ensuring their children embrace similar attitudes. Sherman writes:

“They want to be in the middle, not in a distributional sense but rather in the affective sense of having the habits and desires of the middle class. As long as the wealthy can distance themselves from images of ‘bad’ rich people, their entitlement is acceptable. In fact, it is almost as if they are not rich.”

More here.

Brian Resnick in Vox:

Brian Resnick in Vox: “Lent” opens with a beautifully rendered retelling of the life of Savonarola: his visions of demons, his prophecy, his political meddling and his role in vast historical forces tearing apart Italy and France. We meet a cast of characters, each with the ringing verisimilitude of well-researched, real historical personages from the heretical Count Giovanni Pico della Mirandola to the statesman Lorenzo de’ Medici and various clergy, peasants, nuns and friars of feuding orders. Finally, we come to the martyrdom of Savonarola, hanged over a roaring flame, then cut down to fall into the blaze …

“Lent” opens with a beautifully rendered retelling of the life of Savonarola: his visions of demons, his prophecy, his political meddling and his role in vast historical forces tearing apart Italy and France. We meet a cast of characters, each with the ringing verisimilitude of well-researched, real historical personages from the heretical Count Giovanni Pico della Mirandola to the statesman Lorenzo de’ Medici and various clergy, peasants, nuns and friars of feuding orders. Finally, we come to the martyrdom of Savonarola, hanged over a roaring flame, then cut down to fall into the blaze … T

T That

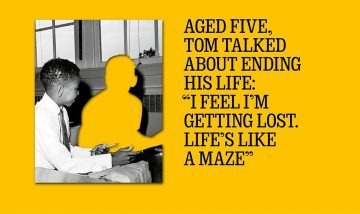

That  Tom remembers the day he decided he wanted to be a theoretical astrophysicist. He was deep into research about black holes, and had amassed a box of papers on his theories. In one he speculated about the relationship between black holes and white holes, hypothetical celestial objects that emit colossal amounts of energy. Black holes, he thought, must be linked across space-time with white holes. “I put them together and I thought, oh wow, that works! That’s when I knew I wanted to do this as a job.” Tom didn’t know enough maths to prove his theory, but he had time to learn. He was only five. Tom is now 11. At home, his favourite way to relax is to devise maths exam papers complete with marking sheets. Last year for Christmas he asked his parents for the £125 registration fee to sit maths

Tom remembers the day he decided he wanted to be a theoretical astrophysicist. He was deep into research about black holes, and had amassed a box of papers on his theories. In one he speculated about the relationship between black holes and white holes, hypothetical celestial objects that emit colossal amounts of energy. Black holes, he thought, must be linked across space-time with white holes. “I put them together and I thought, oh wow, that works! That’s when I knew I wanted to do this as a job.” Tom didn’t know enough maths to prove his theory, but he had time to learn. He was only five. Tom is now 11. At home, his favourite way to relax is to devise maths exam papers complete with marking sheets. Last year for Christmas he asked his parents for the £125 registration fee to sit maths  The work of the AgeLab is shaped by a paradox. Having been established to engineer and promote new products and services specially designed for the expanding market of the aged, the AgeLab swiftly discovered that engineering and promoting new products and services specially designed for the expanding market of the aged is a good way of going out of business. Old people will not buy anything that reminds them that they are old. They are a market that cannot be marketed to. In effect, to accept help in getting out of the suit is to accept that we’re in the suit for life. We would rather suffer because we’re old than accept that we’re old and suffer less.

The work of the AgeLab is shaped by a paradox. Having been established to engineer and promote new products and services specially designed for the expanding market of the aged, the AgeLab swiftly discovered that engineering and promoting new products and services specially designed for the expanding market of the aged is a good way of going out of business. Old people will not buy anything that reminds them that they are old. They are a market that cannot be marketed to. In effect, to accept help in getting out of the suit is to accept that we’re in the suit for life. We would rather suffer because we’re old than accept that we’re old and suffer less. I am truly honored to have been invited by PEN America to deliver this year’s Arthur Miller Freedom to Write Lecture. What better time than this to think together about a place for literature, at this moment when an era that we think we understand – at least vaguely, if not well – is coming to a close.

I am truly honored to have been invited by PEN America to deliver this year’s Arthur Miller Freedom to Write Lecture. What better time than this to think together about a place for literature, at this moment when an era that we think we understand – at least vaguely, if not well – is coming to a close. The scent of lily of the valley cannot be easily bottled. For decades companies that make soap, lotions and perfumes have relied on a chemical called bourgeonal to imbue their products with the sweet smell of the little white flowers. A tiny drop can be extraordinarily intense.

The scent of lily of the valley cannot be easily bottled. For decades companies that make soap, lotions and perfumes have relied on a chemical called bourgeonal to imbue their products with the sweet smell of the little white flowers. A tiny drop can be extraordinarily intense.

“La Petite Irène” was plundered from the Chambord castle on orders of Goering, an obsessive collector who was not a fan of Renoir because Nazis considered his impressionist style degenerate. But he still used the valuable art for trading: Goering swapped the portrait in 1942 for a Florentine Tondo with a Paris gallery dealer who was one of his chief art procurers. Some historians contend that the painting was then bought by another Swiss gallery owner who held it along with others for Bührle because of the growing risks of buying plundered art.

“La Petite Irène” was plundered from the Chambord castle on orders of Goering, an obsessive collector who was not a fan of Renoir because Nazis considered his impressionist style degenerate. But he still used the valuable art for trading: Goering swapped the portrait in 1942 for a Florentine Tondo with a Paris gallery dealer who was one of his chief art procurers. Some historians contend that the painting was then bought by another Swiss gallery owner who held it along with others for Bührle because of the growing risks of buying plundered art. The body knows when it’s in love, and the body knows when it’s ensnared in something beyond endurance. My body knew last summer, as the revelations in Ireland provoked a visceral collapse of faith.

The body knows when it’s in love, and the body knows when it’s ensnared in something beyond endurance. My body knew last summer, as the revelations in Ireland provoked a visceral collapse of faith. The mood of the 1850s and 1860s was vigorous. Muscularity, ‘reality’ and ‘go’ were the admired qualities in art, in science and in life. Problems were there to be solved. Railway companies driving cuttings through the landscape split open dramatic rock strata. Geology and fossil-hunting were crazes, seaside holidaymakers collected shells and fished in rock pools. The world was immanent with new realms of knowledge, and as the meaning of ‘evolution’ shifted towards what was soon called Darwinism, the older meaning still haunted it. From his home in Biddulph Grange in Staffordshire, James Bateman corresponded with Darwin in the course of constructing his Geological Gallery, which opened to the public in 1862. In it the phases of biblical creation were illustrated with geological specimens and fossils in bays labelled ‘Day One’, ‘Day Two’ etc. Neither Bateman nor many of his contemporaries believed in the literal truth of Genesis, but this metaphorical account of ‘development’ as the slow unfolding of God’s creation could hold together science and religion. The churches of the High Victorian years glowed and bristled with inset marble and polished minerals.

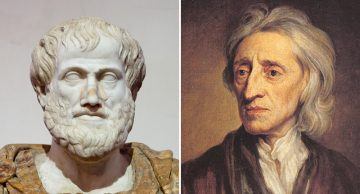

The mood of the 1850s and 1860s was vigorous. Muscularity, ‘reality’ and ‘go’ were the admired qualities in art, in science and in life. Problems were there to be solved. Railway companies driving cuttings through the landscape split open dramatic rock strata. Geology and fossil-hunting were crazes, seaside holidaymakers collected shells and fished in rock pools. The world was immanent with new realms of knowledge, and as the meaning of ‘evolution’ shifted towards what was soon called Darwinism, the older meaning still haunted it. From his home in Biddulph Grange in Staffordshire, James Bateman corresponded with Darwin in the course of constructing his Geological Gallery, which opened to the public in 1862. In it the phases of biblical creation were illustrated with geological specimens and fossils in bays labelled ‘Day One’, ‘Day Two’ etc. Neither Bateman nor many of his contemporaries believed in the literal truth of Genesis, but this metaphorical account of ‘development’ as the slow unfolding of God’s creation could hold together science and religion. The churches of the High Victorian years glowed and bristled with inset marble and polished minerals. One of the most influential thinkers of all time, the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle possessed a wide-ranging and insatiable curiosity. Most of his philosophy is what we would now call science: he wrote on biology, astronomy, zoology, physics, and psychology, to name just a few subjects. He also made important contributions to ethics and political theory. Unfortunately, the only works by Aristotle that have survived appear to be his lecture notes. The 17th-century English philosopher John Locke was a pioneering political thinker. He had a major influence on the U.S. Founding Fathers and provided the philosophical justification for the American Revolution.

One of the most influential thinkers of all time, the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle possessed a wide-ranging and insatiable curiosity. Most of his philosophy is what we would now call science: he wrote on biology, astronomy, zoology, physics, and psychology, to name just a few subjects. He also made important contributions to ethics and political theory. Unfortunately, the only works by Aristotle that have survived appear to be his lecture notes. The 17th-century English philosopher John Locke was a pioneering political thinker. He had a major influence on the U.S. Founding Fathers and provided the philosophical justification for the American Revolution. It’s not just in politics where otherwise smart people consistently talk past one another. People debating whether humans have free will also have this tendency. Neuroscientist and free-will skeptic Sam Harris has dueled philosopher and free-will defender Daniel Dennett for years and once invited him onto his podcast with the express purpose of finally having a meeting of minds. Whoosh! They flew right past each other yet again. Christian List, a philosopher at the London School of Economics who specializes in how humans make decisions, has a new book, Why Free Will Is Real, that tries to bridge the gap. List is one of a youngish generation of thinkers, such as cosmologist Sean Carroll and philosopher Jenann Ismael, who dissolve the old dichotomies on free will and think that a nuanced reading of physics poses no contradiction for it.

It’s not just in politics where otherwise smart people consistently talk past one another. People debating whether humans have free will also have this tendency. Neuroscientist and free-will skeptic Sam Harris has dueled philosopher and free-will defender Daniel Dennett for years and once invited him onto his podcast with the express purpose of finally having a meeting of minds. Whoosh! They flew right past each other yet again. Christian List, a philosopher at the London School of Economics who specializes in how humans make decisions, has a new book, Why Free Will Is Real, that tries to bridge the gap. List is one of a youngish generation of thinkers, such as cosmologist Sean Carroll and philosopher Jenann Ismael, who dissolve the old dichotomies on free will and think that a nuanced reading of physics poses no contradiction for it. In Lucy Ives’s second novel, Loudermilk, a charismatic dumbass scams his way into a prestigious MFA poetry program by submitting the work of his antisocial companion. The real writer, who hates the sound of his own voice, follows the oversexed, symmetrically featured dumbass to school and continues to write for him. It’s a fun setup, but the book aims for more than just comedy. Ives, who once described herself as “the author of some kind of thinking about writing,” examines the conditions that produce authors and their work while never losing a sense of wonder at the sheer mystery of the written word.

In Lucy Ives’s second novel, Loudermilk, a charismatic dumbass scams his way into a prestigious MFA poetry program by submitting the work of his antisocial companion. The real writer, who hates the sound of his own voice, follows the oversexed, symmetrically featured dumbass to school and continues to write for him. It’s a fun setup, but the book aims for more than just comedy. Ives, who once described herself as “the author of some kind of thinking about writing,” examines the conditions that produce authors and their work while never losing a sense of wonder at the sheer mystery of the written word. The Internet was going to set us all free. At least, that is what U.S. policy makers, pundits, and scholars believed in the 2000s. The Internet would undermine authoritarian rulers by reducing the government’s stranglehold on debate, helping oppressed people realize how much they all hated their government, and simply making it easier and cheaper to organize protests.

The Internet was going to set us all free. At least, that is what U.S. policy makers, pundits, and scholars believed in the 2000s. The Internet would undermine authoritarian rulers by reducing the government’s stranglehold on debate, helping oppressed people realize how much they all hated their government, and simply making it easier and cheaper to organize protests.