Charlotte Higgins in The Guardian:

At the centre of Natalie Haynes’s absorbing, fiercely feminist new novel A Thousand Ships, about the women caught up in the Trojan war, is Calliope, the muse of epic poetry. Here, the goddess invoked at the start of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey has something to say about the story that is being told under her guidance:

At the centre of Natalie Haynes’s absorbing, fiercely feminist new novel A Thousand Ships, about the women caught up in the Trojan war, is Calliope, the muse of epic poetry. Here, the goddess invoked at the start of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey has something to say about the story that is being told under her guidance:

There are so many ways of telling a war: the entire conflict can be encapsulated in just one incident. One man’s anger at the behaviour of another, say … But this is the women’s war, just as much as it is men’s, and the poet will look upon their pain – the pain of the women who have always been relegated to the edges of the story, victims of men, survivors of men, slaves of men.

“One man’s anger at the behaviour of another” is a way of summing up the plot of the Iliad: the wrath of Achilles, directed at the Greek commander-in-chief, Agamemnon. The quarrel between the two men, who are ostensibly on the same side, is about the apportioning of loot – predictably enough, a captured woman, Briseis – and the stakes are so high because Achilles is by far the better fighter. When Agamemnon insists on pulling rank and taking Briseis, Achilles withdraws from the conflict, and the Greek invaders of Troy are pushed to the verge of defeat. Eventually, after the death of his beloved companion Patroclus, Achilles enters the battle, and the poem culminates in his slaughtering of Hector, Troy’s greatest warrior.

Haynes’s book is emphatically not this: it is, as Calliope’s intervention explains, the story of the shadowy women on the edges of Homer’s poem, who nonetheless – in Briseis’s case, in Helen of Troy’s case – drive the plot. A Thousand Ships is one of a trio of recent novels by women that, to a greater or lesser degree, rewrite the Homeric epics from the point of view of female characters. Madeline Miller’s beguiling Circe has the witch from the Odysseyat its centre, while Pat Barker’s remarkable The Silence of the Girls retells the Iliad from the perspective of Briseis. Towards the end of Barker’s novel, Briseis ponders how the war will be remembered. “What will they make of us, the people of those unimaginably distant times? One thing I do know: they won’t want the brutal reality of conquest and slavery. They won’t want to be told about the massacres of men and boys, the enslavement of women and girls. They won’t want to know we were living in a rape camp.”

More here.

Stepping inside the Notre Dame is a bit like stepping outside of ordinary time and space. The immense verticality of the entire structure, illuminated from outside through light refracted in the colors of the stained glass, isn’t accidental in its immediate effects on our consciousness. We are meant to experience our own smallness relative to its vastness; we are meant to be drawn upwards towards the light pouring in from all sides, and to recognize it as symbolic of an external revelation that illuminates and transfigures our minds and hearts. Her rose windows are meant to be occasions to contemplate the mysteries of human life—birth, love, sex, death—and the nature of eternity. As we enter, we are meant to feel deep in our hearts a yearning for that which is greater than ourselves; if we do not experience this awe and wonder, or stop to contemplate the depths of these mysteries, we have missed something of the structure’s essential intent.

Stepping inside the Notre Dame is a bit like stepping outside of ordinary time and space. The immense verticality of the entire structure, illuminated from outside through light refracted in the colors of the stained glass, isn’t accidental in its immediate effects on our consciousness. We are meant to experience our own smallness relative to its vastness; we are meant to be drawn upwards towards the light pouring in from all sides, and to recognize it as symbolic of an external revelation that illuminates and transfigures our minds and hearts. Her rose windows are meant to be occasions to contemplate the mysteries of human life—birth, love, sex, death—and the nature of eternity. As we enter, we are meant to feel deep in our hearts a yearning for that which is greater than ourselves; if we do not experience this awe and wonder, or stop to contemplate the depths of these mysteries, we have missed something of the structure’s essential intent.

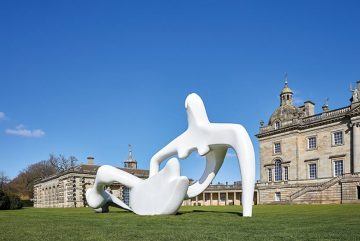

It seemed that Moore needed to start with natural forms, but then move away from them. You don’t really need to know that ‘Arch’ or ‘Three Piece Sculpture’ were inspired by bones in order to enjoy them. What’s important is that, as he said, the sculpture has ‘a force, a strength, a life, a vitality from inside’. And these really do.

It seemed that Moore needed to start with natural forms, but then move away from them. You don’t really need to know that ‘Arch’ or ‘Three Piece Sculpture’ were inspired by bones in order to enjoy them. What’s important is that, as he said, the sculpture has ‘a force, a strength, a life, a vitality from inside’. And these really do. You can find the news about Pakistan’s war on women buried deep inside the metro pages of Urdu newspapers. I stumbled upon it a few years ago. I noticed that I could pick up my newspaper and almost every day find news about a murdered woman. I thought maybe it’s a coincidence, maybe Karachi is a huge city, these things happen. But it went on and on. It became so routine that I could pick up the paper, open the exact same pages, just like you can bet that you’ll find a crossword or letters to the editor, and it was always there.

You can find the news about Pakistan’s war on women buried deep inside the metro pages of Urdu newspapers. I stumbled upon it a few years ago. I noticed that I could pick up my newspaper and almost every day find news about a murdered woman. I thought maybe it’s a coincidence, maybe Karachi is a huge city, these things happen. But it went on and on. It became so routine that I could pick up the paper, open the exact same pages, just like you can bet that you’ll find a crossword or letters to the editor, and it was always there. Ice remembers forest fires and rising seas. Ice remembers the chemical composition of the air around the start of the last Ice Age, 110,000 years ago. It remembers how many days of sunshine fell upon it in a summer 50,000 years ago. It remembers the temperature in the clouds at a moment of snowfall early in the

Ice remembers forest fires and rising seas. Ice remembers the chemical composition of the air around the start of the last Ice Age, 110,000 years ago. It remembers how many days of sunshine fell upon it in a summer 50,000 years ago. It remembers the temperature in the clouds at a moment of snowfall early in the  Nusrat Jahan Rafi

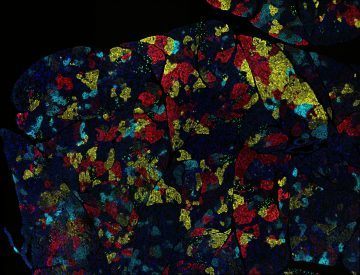

Nusrat Jahan Rafi To better understand and treat cancer, physicians need to stop oversimplifying its causes. Cancer results not solely from genetic mutations but by adapting to and thriving in micro-environments in the body.

To better understand and treat cancer, physicians need to stop oversimplifying its causes. Cancer results not solely from genetic mutations but by adapting to and thriving in micro-environments in the body. New research has shown that the last surviving flightless species of bird, a type of rail, in the Indian Ocean had previously gone extinct but rose from the dead thanks to a rare process called ‘iterative evolution’. The research, from the University of Portsmouth and Natural History Museum, found that on two occasions, separated by tens of thousands of years, a rail species was able to successfully colonise an isolated atoll called Aldabra and subsequently became flightless on both occasions. The last surviving colony of flightless rails is still found on the island today.

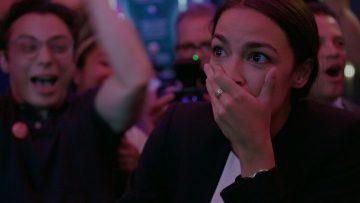

New research has shown that the last surviving flightless species of bird, a type of rail, in the Indian Ocean had previously gone extinct but rose from the dead thanks to a rare process called ‘iterative evolution’. The research, from the University of Portsmouth and Natural History Museum, found that on two occasions, separated by tens of thousands of years, a rail species was able to successfully colonise an isolated atoll called Aldabra and subsequently became flightless on both occasions. The last surviving colony of flightless rails is still found on the island today. A scene near the end of the new documentary Knock Down the House finds Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, five days after her surprise win in the 2018 primary, visiting the landmark that would soon become her office. Perched on a ledge in front of the U.S. Capitol, the building sprawling and gleaming in the midsummer sun, the Democratic nominee for New York’s 14th Congressional District talks about an earlier visit to Washington, D.C. “When I was a little girl, my dad wanted to go on a road trip with his buddies,” she says. “I wanted to go so badly. And I begged and I begged and I begged, and he relented. And so it was like four grown men and a 5-year-old girl went on this road trip from New York. And we stopped—we stopped here.”

A scene near the end of the new documentary Knock Down the House finds Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, five days after her surprise win in the 2018 primary, visiting the landmark that would soon become her office. Perched on a ledge in front of the U.S. Capitol, the building sprawling and gleaming in the midsummer sun, the Democratic nominee for New York’s 14th Congressional District talks about an earlier visit to Washington, D.C. “When I was a little girl, my dad wanted to go on a road trip with his buddies,” she says. “I wanted to go so badly. And I begged and I begged and I begged, and he relented. And so it was like four grown men and a 5-year-old girl went on this road trip from New York. And we stopped—we stopped here.” Mountain climbing is a beloved metaphor for mathematical research. The comparison is almost inevitable: The frozen world, the cold thin air and the implacable harshness of mountaineering reflect the unforgiving landscape of numbers, formulas and theorems. And just as a climber pits his abilities against an unyielding object — in his case, a sheer wall of stone — a mathematician often finds herself engaged in an individual battle of the human mind against rigid logic.

Mountain climbing is a beloved metaphor for mathematical research. The comparison is almost inevitable: The frozen world, the cold thin air and the implacable harshness of mountaineering reflect the unforgiving landscape of numbers, formulas and theorems. And just as a climber pits his abilities against an unyielding object — in his case, a sheer wall of stone — a mathematician often finds herself engaged in an individual battle of the human mind against rigid logic. Across the political spectrum, a consensus has arisen that Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, and other digital platforms are laying ruin to public discourse. They trade on snarkiness, trolling, outrage, and conspiracy theories, and encourage tribalism, information bubbles, and social discord. How did we get here, and how can we get out? The essays in this symposium seek answers to the crisis of “digital discourse” beyond privacy policies, corporate exposés, and smarter algorithms.

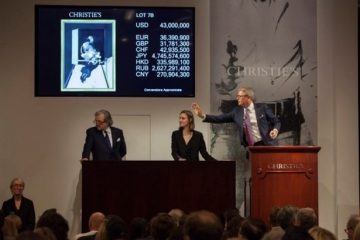

Across the political spectrum, a consensus has arisen that Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, and other digital platforms are laying ruin to public discourse. They trade on snarkiness, trolling, outrage, and conspiracy theories, and encourage tribalism, information bubbles, and social discord. How did we get here, and how can we get out? The essays in this symposium seek answers to the crisis of “digital discourse” beyond privacy policies, corporate exposés, and smarter algorithms. Looking at this market through the eyes of an investor, what can art offer? Like, say, real estate, it boasts strong capital gains over the longer term. Of the 600% growth in turnover since 1990, price escalation has been a major contributor, albeit skewed toward higher priced works. Advocates say that returns on art investments are uncorrelated with the returns from other asset classes, making it attractive for inclusion in a diversified portfolio. Art is both durable and highly mobile. Various airports in Europe and elsewhere host tax free storage zones where valuable artworks can be held. If a painting quietly changes hands and moves from one storage suite to another, who is to know? Individuals unhappy with their tax bills or nervous about their spouse’s divorce lawyers have been known to exploit these characteristics to great effect. And, of course, art emphatically offers aesthetic returns – it looks great on the living room walls while you await the capital gains.

Looking at this market through the eyes of an investor, what can art offer? Like, say, real estate, it boasts strong capital gains over the longer term. Of the 600% growth in turnover since 1990, price escalation has been a major contributor, albeit skewed toward higher priced works. Advocates say that returns on art investments are uncorrelated with the returns from other asset classes, making it attractive for inclusion in a diversified portfolio. Art is both durable and highly mobile. Various airports in Europe and elsewhere host tax free storage zones where valuable artworks can be held. If a painting quietly changes hands and moves from one storage suite to another, who is to know? Individuals unhappy with their tax bills or nervous about their spouse’s divorce lawyers have been known to exploit these characteristics to great effect. And, of course, art emphatically offers aesthetic returns – it looks great on the living room walls while you await the capital gains. Mao was born in Wuhan, China, and moved to the United States at age five. She draws upon her experience of Chinese and Asian American visual culture, which saturates the book with allusions so dense the text requires endnotes. Her landscape is the detritus of television and cinema and internet webcams, the jetstream of the image in an era when most everything has become visual matter. In the aforementioned interview with the Creative Independent, Mao describes the themes at the heart of Oculus: “It’s obsessed with spectacle and being looked at, but it also is aware of all the violence that comes with being looked at.”

Mao was born in Wuhan, China, and moved to the United States at age five. She draws upon her experience of Chinese and Asian American visual culture, which saturates the book with allusions so dense the text requires endnotes. Her landscape is the detritus of television and cinema and internet webcams, the jetstream of the image in an era when most everything has become visual matter. In the aforementioned interview with the Creative Independent, Mao describes the themes at the heart of Oculus: “It’s obsessed with spectacle and being looked at, but it also is aware of all the violence that comes with being looked at.” I manage to travel two weeks after the cyclone. The pilot of the plane is a friend and he tells me that he is going to fly over the area around my city so that I can see the extent of the flooding. He’s right to show me: for miles around, the land is sea. Villages and small towns that I would normally recognize are still under water. I regret sitting next to the window. I regret not taking Dany’s advice to cancel my trip. I remember the moment my brothers decided to go to visit the body of my father in the morgue. I refused to go with them. I wanted to find again the living expression and warm hands of the man who gave me life. And once more, I’m torn apart by what I must confront. Beneath me is my decapitated city. I have to wipe my eyes to keep on looking. The other passengers are filming and taking photographs. And all this is unreal to me. I’m the last to leave the plane, as if afraid of not knowing how to walk on that ground, my first ground. As children, we don’t say goodbye to places. We always think that we’ll come back. We believe that it’s never the last time. And that trip had the bitter taste of goodbye.

I manage to travel two weeks after the cyclone. The pilot of the plane is a friend and he tells me that he is going to fly over the area around my city so that I can see the extent of the flooding. He’s right to show me: for miles around, the land is sea. Villages and small towns that I would normally recognize are still under water. I regret sitting next to the window. I regret not taking Dany’s advice to cancel my trip. I remember the moment my brothers decided to go to visit the body of my father in the morgue. I refused to go with them. I wanted to find again the living expression and warm hands of the man who gave me life. And once more, I’m torn apart by what I must confront. Beneath me is my decapitated city. I have to wipe my eyes to keep on looking. The other passengers are filming and taking photographs. And all this is unreal to me. I’m the last to leave the plane, as if afraid of not knowing how to walk on that ground, my first ground. As children, we don’t say goodbye to places. We always think that we’ll come back. We believe that it’s never the last time. And that trip had the bitter taste of goodbye. First published in 1964, Susan Sontag’s essay Notes on Camp remains a groundbreaking piece of cultural activism. Sontag’s achievement was to give a name to an aesthetic that was everywhere yet until then had gone largely unremarked. It was visible in

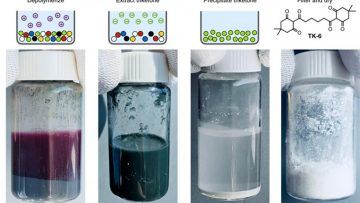

First published in 1964, Susan Sontag’s essay Notes on Camp remains a groundbreaking piece of cultural activism. Sontag’s achievement was to give a name to an aesthetic that was everywhere yet until then had gone largely unremarked. It was visible in  Plastic pollution in the world’s oceans may have an impact of $ 2.5 billion, adversely affecting “almost all marine ecosystem services”, including areas such as fishing, recreation and heritage. But a breakthrough from researchers at Berkeley Lab may be the solution the planet needs for this eye-opening problem – recyclable plastic. The study, published in Nature Chemistry, describes how the researchers could find a new way to assemble plastic and reuse them “to new materials of any color, shape or shape.” “Most plastic materials were never made to be recycled,” says senior author Peter Christensen, a postdoctoral researcher at Berkeley Lab’s molecular foundry, in the statement. “But we have discovered a new way to assemble plastic that takes into account recycling from a molecular perspective.”

Plastic pollution in the world’s oceans may have an impact of $ 2.5 billion, adversely affecting “almost all marine ecosystem services”, including areas such as fishing, recreation and heritage. But a breakthrough from researchers at Berkeley Lab may be the solution the planet needs for this eye-opening problem – recyclable plastic. The study, published in Nature Chemistry, describes how the researchers could find a new way to assemble plastic and reuse them “to new materials of any color, shape or shape.” “Most plastic materials were never made to be recycled,” says senior author Peter Christensen, a postdoctoral researcher at Berkeley Lab’s molecular foundry, in the statement. “But we have discovered a new way to assemble plastic that takes into account recycling from a molecular perspective.”