by Tim Sommers

“The world was so recent that many things lacked names, and in order to indicate them it was necessary to point.” –Gabriel Garcia Marquez in One Hundred Years of Solitude

Here’s an apocryphal story that is so good, it should be true. In 1770 Captain Cook became the first European to land in Australia and so the first to encounter a leaping animal with a baby in its pouch. He pointed at it and asked a nearby aboriginal, “What is that?”

“Kan-ga-roo,” our fictional indigenous person responded. And, so, we call them “kangaroos”. Which means, in that local language, “I don’t know what you are saying.”

I always associate that story with Willard Van Orman Quine’s essay, “Ontological Relativity”, because the centerpiece of the essay is what he calls a “radical translation” scenario. We are trying to learn to translate a language that we have no independent knowledge of, a language that, as far as we know, is not related to any other language that we already know how to translate. Suppose a rabbit goes hopping by and a native speaker points at it saying, “Gavagi!” Even assuming we all agree on what pointing is, and we all think that pointing and talking at the same time associates the pointing with the talking, and we are sure that the spatio-temporal area occupied by what we would call a rabbit is what is being pointed at, assuming all that, how do we know whether they mean “There goes a rabbit!” or “Look at those undetached-rabbit-parts!” or “Some rabbitizing is going on over there”. Or, if you do the pointing, how do you know that what they are saying to you is not just, “I don’t know what you are saying”.

I know, I know, only a philosopher would wonder that. But, consider: what we think exists should be revealed by what we say, but what if it’s not? What if what exists is relative to what we say, but we can never be absolutely sure what anyone is saying about what there is? What if ontology, the part of metaphysics that is supposed to be, at a minimum, a catalogue of things that we think exist and are real, is relative to language and language is always indeterminate with respect to ontology. Should we be worried about this? Read more »

Having before you an iced mango

Having before you an iced mango

I don’t know anything about music. I make art, and like many artists I listen to music while working. Nearly every kind of music, but mostly metal for those time-to-get-serious moments. Atmospheric black metal with little discernible speech tends to work best, because it provides a setting such that one can become lost in the droning distortions when working on something. The music I like to hear is that which Kant would endorse as sublime – enormous walls of sound that result in a distractedness where one can go undeterred by outside forces. Of course an fMRI could show what is happening in the brain, what psychically galvanizes me while I listen to music in those moments, but I’m less interested in what’s happening to me as much as what’s happening to it: what happens to artworks when produced to a soundtrack?

I don’t know anything about music. I make art, and like many artists I listen to music while working. Nearly every kind of music, but mostly metal for those time-to-get-serious moments. Atmospheric black metal with little discernible speech tends to work best, because it provides a setting such that one can become lost in the droning distortions when working on something. The music I like to hear is that which Kant would endorse as sublime – enormous walls of sound that result in a distractedness where one can go undeterred by outside forces. Of course an fMRI could show what is happening in the brain, what psychically galvanizes me while I listen to music in those moments, but I’m less interested in what’s happening to me as much as what’s happening to it: what happens to artworks when produced to a soundtrack? The wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have gone on so long that the Middle East war novel has itself become a crusty genre — a familiar set of echoes coming back to us from ravaged lands. Many of these books are stirring on the level of detail but an equal number thoughtlessly valorize the American soldier or wallow in the morally vacuous conclusion that war is hell and that’s that. Where is the ferocious “Catch-22” of these benighted conflicts? Who will have the temerity to make these wars the subject of bracing comedy?

The wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have gone on so long that the Middle East war novel has itself become a crusty genre — a familiar set of echoes coming back to us from ravaged lands. Many of these books are stirring on the level of detail but an equal number thoughtlessly valorize the American soldier or wallow in the morally vacuous conclusion that war is hell and that’s that. Where is the ferocious “Catch-22” of these benighted conflicts? Who will have the temerity to make these wars the subject of bracing comedy? Jared Diamond’s new book,

Jared Diamond’s new book,  On a recent afternoon in Helsinki, a group of students gathered to hear a lecture on a subject that is far from a staple in most community college curriculums.

On a recent afternoon in Helsinki, a group of students gathered to hear a lecture on a subject that is far from a staple in most community college curriculums. This January, Hussein Fancy, an American academic of Pakistani origin, received the Herbert Baxter Adams Prize, awarded annually by the American Historical Association “to honor a distinguished book published in English in the field of European history,” for his groundbreaking work The Mercenary Mediterranean: Sovereignty, Religion, and Violence in the Medieval Crown of Aragon. This isn’t the first prize awarded to this book: it had earlier been the recipient of the Jans F. Verbruggen Prize from De Re Militari for the best book in medieval military history and the L. Carl Brown AIMS Book Prize in North African Studies. These three very different prizes, each with different parameters, indicate the range and importance of Fancy’s research.

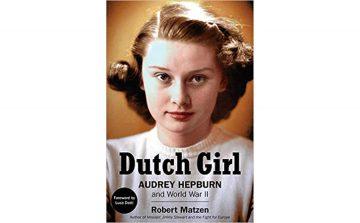

This January, Hussein Fancy, an American academic of Pakistani origin, received the Herbert Baxter Adams Prize, awarded annually by the American Historical Association “to honor a distinguished book published in English in the field of European history,” for his groundbreaking work The Mercenary Mediterranean: Sovereignty, Religion, and Violence in the Medieval Crown of Aragon. This isn’t the first prize awarded to this book: it had earlier been the recipient of the Jans F. Verbruggen Prize from De Re Militari for the best book in medieval military history and the L. Carl Brown AIMS Book Prize in North African Studies. These three very different prizes, each with different parameters, indicate the range and importance of Fancy’s research. Audrey Hepburn was one of the most celebrated actresses of the 20th century and a winner of Academy, Tony, Grammy, and Emmy awards. She was a style icon and, in later life, a tireless humanitarian who worked to improve conditions for children in some of the poorest communities in Africa and Asia as an ambassador for UNICEF. But this extraordinary individual was the product of an extremely difficult childhood. Her father was a British subject and something of a rake and her mother was a minor Dutch noblewoman. Both of her parents flirted with the Nazis in the 1930s. Her mother met Adolf Hitler and wrote favorable articles about him for the British Union of Fascists. After abandoning the family in 1935, her father moved to England and became so active with Oswald Mosley’s fascists that he was interned during World War II. As a child, Hepburn rarely saw him.

Audrey Hepburn was one of the most celebrated actresses of the 20th century and a winner of Academy, Tony, Grammy, and Emmy awards. She was a style icon and, in later life, a tireless humanitarian who worked to improve conditions for children in some of the poorest communities in Africa and Asia as an ambassador for UNICEF. But this extraordinary individual was the product of an extremely difficult childhood. Her father was a British subject and something of a rake and her mother was a minor Dutch noblewoman. Both of her parents flirted with the Nazis in the 1930s. Her mother met Adolf Hitler and wrote favorable articles about him for the British Union of Fascists. After abandoning the family in 1935, her father moved to England and became so active with Oswald Mosley’s fascists that he was interned during World War II. As a child, Hepburn rarely saw him. It’s a well-known saying that women lost us the empire,” the film director David Lean said in 1985. “It’s true.” He’d just released his acclaimed adaptation of A Passage to India, EM Forster’s novel in which a British woman’s accusation of sexual assault compromises a friendship between British and Indian men. Misogyny may not be the first prejudice associated with British imperialists, but it has proved as enduring as it was powerful. As Katie Hickman discovered when she started writing about British women in India, Lean’s view (if not Forster’s) “remains stubbornly embedded in our consciousness”. “Everyone” she talked to “knew that if it were not for the snobbery and racial prejudice of the memsahibs there would, somehow, have been far greater harmony and accord between the races”. Her book, vivaciously written and richly descriptive, offers a rebuke to such stereotypes. She animates a cast of British women who travelled to India before the 1857 rebellion. They included “bakers, dressmakers, actresses, portrait painters, maids, shopkeepers, governesses, teachers, boarding house proprietors … missionaries, doctors, geologists, plant-collectors, writers … even traders” – and some of them might not have been out of place in a Lean epic of their own.

It’s a well-known saying that women lost us the empire,” the film director David Lean said in 1985. “It’s true.” He’d just released his acclaimed adaptation of A Passage to India, EM Forster’s novel in which a British woman’s accusation of sexual assault compromises a friendship between British and Indian men. Misogyny may not be the first prejudice associated with British imperialists, but it has proved as enduring as it was powerful. As Katie Hickman discovered when she started writing about British women in India, Lean’s view (if not Forster’s) “remains stubbornly embedded in our consciousness”. “Everyone” she talked to “knew that if it were not for the snobbery and racial prejudice of the memsahibs there would, somehow, have been far greater harmony and accord between the races”. Her book, vivaciously written and richly descriptive, offers a rebuke to such stereotypes. She animates a cast of British women who travelled to India before the 1857 rebellion. They included “bakers, dressmakers, actresses, portrait painters, maids, shopkeepers, governesses, teachers, boarding house proprietors … missionaries, doctors, geologists, plant-collectors, writers … even traders” – and some of them might not have been out of place in a Lean epic of their own. Emily Wilson in The New Statesman:

Emily Wilson in The New Statesman: Jan-Werner Müller in The Nation:

Jan-Werner Müller in The Nation: