Quassim Cassam at the Institute of Art and Ideas:

Conspiracy theorists get a seriously bad press. Gullible, irresponsible, paranoid, stupid. These are some of the politer labels applied to them, usually by establishment figures who aren’t averse to promoting their own conspiracy theories when it suits them. President George W. Bush denounced outrageous conspiracy theories about 9/11 while his own administration was busy promoting the outrageous conspiracy theory that Iraq was behind 9/11.

Conspiracy theorists get a seriously bad press. Gullible, irresponsible, paranoid, stupid. These are some of the politer labels applied to them, usually by establishment figures who aren’t averse to promoting their own conspiracy theories when it suits them. President George W. Bush denounced outrageous conspiracy theories about 9/11 while his own administration was busy promoting the outrageous conspiracy theory that Iraq was behind 9/11.

If the abuse isn’t bad enough, conspiracy theorists now have the dubious honour of being studied by psychologists. The psychology of conspiracy theories is a thing, and the news for conspiracy theorists isn’t good. A recent study describes their theories as ‘corrosive to societal and individual well-being’. Conspiracy theorists, the study reveals, are more likely to be male, unmarried, less educated, have lower household incomes and see themselves as having low social standing. They have lower levels of physical and psychological well-being and are more likely to meet the criteria for having a psychiatric disorder.

In case you’re starting to feel a sorry for conspiracy theorists (or for yourself if you are one), perhaps it’s worth remembering that they aren’t exactly shrinking violets. They are vociferous defenders of their theories and scornful of their opponents. Anyone who has been on the receiving end of the wrath of conspiracy theorists will know that it can be a bruising experience.

More here.

Murray Gell-Mann (

Murray Gell-Mann (

All the same, some of the confusion and apathy in the aftermath of the explosion of Reactor Four was due to an inability to comprehend the enormity of what had happened: that the reactor and the hall housing it had literally been blown apart, its pieces scattered still glowing across the site and the fiery inner core exposed to the atmosphere. There is a sense in these accounts of the truly unearthly: Higginbotham mentions the “shimmering pillar of ethereal blue-white light, reaching straight up into the night sky, disappearing into infinity” as the intense radiation streaming from the reactor ionised the air itself. Senior figures wandered around the site in a daze, muttering about routine malfunctions even as they kicked aside immensely radioactive debris from the reactor core. Radiation levels at the site were so far off the scale that they defied belief and comprehension. Meanwhile, in Pripyat life went on as normal for a day and a half, children playing in the warm spring sunshine. A film taken of those events is marred by ghostly flashes and white streaks: ambient radiation burning itself into the celluloid.

All the same, some of the confusion and apathy in the aftermath of the explosion of Reactor Four was due to an inability to comprehend the enormity of what had happened: that the reactor and the hall housing it had literally been blown apart, its pieces scattered still glowing across the site and the fiery inner core exposed to the atmosphere. There is a sense in these accounts of the truly unearthly: Higginbotham mentions the “shimmering pillar of ethereal blue-white light, reaching straight up into the night sky, disappearing into infinity” as the intense radiation streaming from the reactor ionised the air itself. Senior figures wandered around the site in a daze, muttering about routine malfunctions even as they kicked aside immensely radioactive debris from the reactor core. Radiation levels at the site were so far off the scale that they defied belief and comprehension. Meanwhile, in Pripyat life went on as normal for a day and a half, children playing in the warm spring sunshine. A film taken of those events is marred by ghostly flashes and white streaks: ambient radiation burning itself into the celluloid. In 1534 an Ottoman delegation was in Paris to discuss a plan to unite France and Turkey against their shared enemy, the Habsburg empire. That François I should lavish courtesies on infidel diplomats was bitterly resented by French Lutherans, who were being persecuted after the “affair of the placards”: a scandalous denunciation of the Catholic mass had been discovered pinned to the door of the royal bedchamber; the Turkish visitors were escorted past pyres that would be fed by Protestant heretics. A decade later the Franco-Ottoman alliance was so fixed a part of the European scene that François allowed a Turkish fleet under Hayreddin Pasha to winter in Toulon, the Mediterranean port having been emptied of its Christian inhabitants. The church bells were silenced and cantatas in the cathedral gave way to the call to prayer.“Looking at Toulon,” remarked an eyewitness after the Ottoman sailors had settled in, “you would say that it was Istanbul, with great public order and justice.”

In 1534 an Ottoman delegation was in Paris to discuss a plan to unite France and Turkey against their shared enemy, the Habsburg empire. That François I should lavish courtesies on infidel diplomats was bitterly resented by French Lutherans, who were being persecuted after the “affair of the placards”: a scandalous denunciation of the Catholic mass had been discovered pinned to the door of the royal bedchamber; the Turkish visitors were escorted past pyres that would be fed by Protestant heretics. A decade later the Franco-Ottoman alliance was so fixed a part of the European scene that François allowed a Turkish fleet under Hayreddin Pasha to winter in Toulon, the Mediterranean port having been emptied of its Christian inhabitants. The church bells were silenced and cantatas in the cathedral gave way to the call to prayer.“Looking at Toulon,” remarked an eyewitness after the Ottoman sailors had settled in, “you would say that it was Istanbul, with great public order and justice.” You wake up on a bus, surrounded by all your remaining ossessions. A few fellow passengers slump on pale blue seats around you, their heads resting against the windows. You turn and see a father holding his son. Almost everyone is asleep. But one man, with a salt-and-pepper beard and khaki vest, stands near the back of the bus, staring at you. You feel uneasy and glance at the driver, wondering if he would help you if you needed it. When you turn back around, the bearded man has moved toward you and is now just a few feet away. You jolt, fearing for your safety, but then remind yourself there’s nothing to worry about. You take off the Oculus helmet and find yourself back in the real world, in Jeremy Bailenson’s Virtual Human Interaction Lab at Stanford University.

You wake up on a bus, surrounded by all your remaining ossessions. A few fellow passengers slump on pale blue seats around you, their heads resting against the windows. You turn and see a father holding his son. Almost everyone is asleep. But one man, with a salt-and-pepper beard and khaki vest, stands near the back of the bus, staring at you. You feel uneasy and glance at the driver, wondering if he would help you if you needed it. When you turn back around, the bearded man has moved toward you and is now just a few feet away. You jolt, fearing for your safety, but then remind yourself there’s nothing to worry about. You take off the Oculus helmet and find yourself back in the real world, in Jeremy Bailenson’s Virtual Human Interaction Lab at Stanford University.

Most of the Universe is missing and decades of searching have so far elicited no sign of it. For some scientists this is an embarrassment. For others it is a clue that might eventually push physics towards the next frontier of understanding. Either way, it is an odd situation.

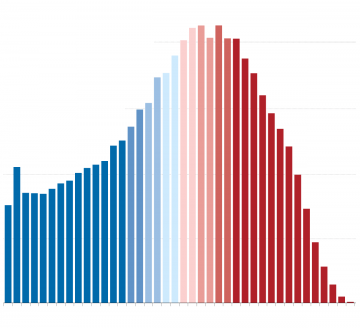

Most of the Universe is missing and decades of searching have so far elicited no sign of it. For some scientists this is an embarrassment. For others it is a clue that might eventually push physics towards the next frontier of understanding. Either way, it is an odd situation. It’s true across many industrialized democracies that rural areas lean conservative while cities tend to be more liberal, a pattern partly rooted in the history of workers’ parties that grew up where urban factories did.

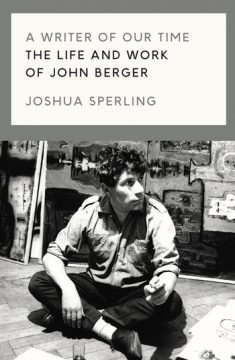

It’s true across many industrialized democracies that rural areas lean conservative while cities tend to be more liberal, a pattern partly rooted in the history of workers’ parties that grew up where urban factories did. John Berger became a writer you might find on television because of Ways of Seeing, the 1972 BBC series that became a short and very famous book. The show presented observations now common to pop-culture reviews—publicity “proposes to each of us that we transform ourselves, or our lives, by buying something more”—in a place (a box!) that rarely admitted critique beyond yea or nay. The book version of Ways of Seeing, which combined photos and text in a montage format, is now a staple of critical-writing syllabi. Writers like Laura Mulvey and Rosalind Krauss wrote the definitive versions of theories Berger proposed, and dozens of critics have put in decades peeling back the semiotic layers of images. Berger simply made it seem plausible that there would be an audience—possibly a big one—for this kind of thinking. In May of 2017, four months after Berger’s death, feminist media scholar Jane Gaines wrote about Ways of Seeing: “We learned from him to see that basic assumptions about everything—work, play, art, commerce—are hidden in the surrounding culture of images.”

John Berger became a writer you might find on television because of Ways of Seeing, the 1972 BBC series that became a short and very famous book. The show presented observations now common to pop-culture reviews—publicity “proposes to each of us that we transform ourselves, or our lives, by buying something more”—in a place (a box!) that rarely admitted critique beyond yea or nay. The book version of Ways of Seeing, which combined photos and text in a montage format, is now a staple of critical-writing syllabi. Writers like Laura Mulvey and Rosalind Krauss wrote the definitive versions of theories Berger proposed, and dozens of critics have put in decades peeling back the semiotic layers of images. Berger simply made it seem plausible that there would be an audience—possibly a big one—for this kind of thinking. In May of 2017, four months after Berger’s death, feminist media scholar Jane Gaines wrote about Ways of Seeing: “We learned from him to see that basic assumptions about everything—work, play, art, commerce—are hidden in the surrounding culture of images.” And we abolish the idea of hell at the very moment when it could be the most pertinent to us. An ironic reality in an era where the world becomes seemingly more hellish, when humanity has developed the ability to enact a type of burning punishment upon the earth itself. Journalist David Wallace-Wells in his terrifying new book about climate change The Uninhabitable Earth: Life After Warming writes that “it is much, much worse, than you think.” Wallace-Wells goes onto describe how anthropogenic warming will result in a twenty-first century that sees coastal cities destroyed and refugees forced to migrate for survival, that will see famines across formerly verdant farm lands and the development of new epidemics that will kill millions, which will see wars fought over fresh water and wildfires scorching the wilderness. Climate change implies not just ecological collapse, but societal, political, and moral collapse as well. The science has been clear for over a generation, our reliance on fossil fuels has been hastening an industrial apocalypse of our own invention. Wallace-Wells is critical of what he describes as the “eerily banal language of climatology,” where the purposefully sober, logical, and rational arguments of empirical science have unintentionally helped to obscure the full extent of what some studying climate change now refer to as our coming “century of hell.” Better perhaps to have this discussion using the language of Revelation, where the horseman of pestilence, war, famine, and death are powered by carbon dioxide.

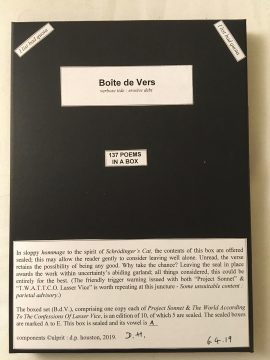

And we abolish the idea of hell at the very moment when it could be the most pertinent to us. An ironic reality in an era where the world becomes seemingly more hellish, when humanity has developed the ability to enact a type of burning punishment upon the earth itself. Journalist David Wallace-Wells in his terrifying new book about climate change The Uninhabitable Earth: Life After Warming writes that “it is much, much worse, than you think.” Wallace-Wells goes onto describe how anthropogenic warming will result in a twenty-first century that sees coastal cities destroyed and refugees forced to migrate for survival, that will see famines across formerly verdant farm lands and the development of new epidemics that will kill millions, which will see wars fought over fresh water and wildfires scorching the wilderness. Climate change implies not just ecological collapse, but societal, political, and moral collapse as well. The science has been clear for over a generation, our reliance on fossil fuels has been hastening an industrial apocalypse of our own invention. Wallace-Wells is critical of what he describes as the “eerily banal language of climatology,” where the purposefully sober, logical, and rational arguments of empirical science have unintentionally helped to obscure the full extent of what some studying climate change now refer to as our coming “century of hell.” Better perhaps to have this discussion using the language of Revelation, where the horseman of pestilence, war, famine, and death are powered by carbon dioxide. I received d.p. houston’s poetry collection Boîte de Vers in the post last week. It’s completely unreadable, but not in the sense that it’s bad. It could well be, but I have no idea because it comes in a sealed box, ‘in sloppy hommage to the spirit of Schrödinger’s Cat’. There are apparently five of these boxes in circulation; mine is lettered A. The precise nature of its contents is indeterminate. I could break the seal of strong black tape and open the box, but doing so would alter it. Not least because I would then be required to fill in the attached label with a cross or tick ‘to indicate whether or not the intrusion comes to be regretted’. It feels like a puzzle, or a personality test: what kind of person would open the box?

I received d.p. houston’s poetry collection Boîte de Vers in the post last week. It’s completely unreadable, but not in the sense that it’s bad. It could well be, but I have no idea because it comes in a sealed box, ‘in sloppy hommage to the spirit of Schrödinger’s Cat’. There are apparently five of these boxes in circulation; mine is lettered A. The precise nature of its contents is indeterminate. I could break the seal of strong black tape and open the box, but doing so would alter it. Not least because I would then be required to fill in the attached label with a cross or tick ‘to indicate whether or not the intrusion comes to be regretted’. It feels like a puzzle, or a personality test: what kind of person would open the box? Minute fossils pulled from remote Arctic Canada could push back the first known appearance of fungi to about one billion years ago — more than 500 million years earlier than scientists had expected. These ur-fungi, described on 22 May in Nature

Minute fossils pulled from remote Arctic Canada could push back the first known appearance of fungi to about one billion years ago — more than 500 million years earlier than scientists had expected. These ur-fungi, described on 22 May in Nature Dear Massimo,

Dear Massimo, For me personally, the vision that became Wolfram|Alpha has a very long history. I first imagined creating something like it more than 47 years ago,

For me personally, the vision that became Wolfram|Alpha has a very long history. I first imagined creating something like it more than 47 years ago,