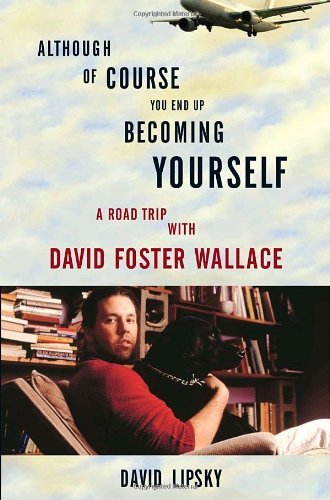

David Lipsky is a contributing editor at Rolling Stone and the author of Although of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself: A Road Trip with David Foster Wallace. Crafted out of transcripts of a five day-long conversation between Lipsky and Wallace on the tail end of the publicity tour for Wallace’s breakthrough novel Infinite Jest, the book reveals facets of the beloved author that have never before been seen publicly. Colin Marshall originally conducted this interview on the public radio program and podcast The Marketplace of Ideas. [MP3] [iTunes]

I want to tell you one thing I imagine about the creation of this book. Tell me if it's right or wrong. As the listener probably knows by now, this book is made out of transcripts of tapes you recorded while you were on the road with David Foster Wallace for five days during his publicity tour for his big novel in '96 Infinite Jest.

I want to tell you one thing I imagine about the creation of this book. Tell me if it's right or wrong. As the listener probably knows by now, this book is made out of transcripts of tapes you recorded while you were on the road with David Foster Wallace for five days during his publicity tour for his big novel in '96 Infinite Jest.

Yeah, it was a lot of fun.

It sounds like it. You didn't end up writing the article that these notes were for, a Rolling Stone profile. That got canceled. So you had these laying around, I presume, stored somewhere. I would imagine, after David Foster Wallace's untimely death in 2008, your mind went immediately to these materials, all this conversation you had with Wallace. I imagine a huge, crushing sense of responsibility. You're thinking, “I've got to do something with themes, but what?” Is that accurate at all?

Well, no — it's interesting, but when I first heard that he had died, like a lot of people, I didn't think it was true. I got an e-mail from a friend, and I assumed it was a prank. Spending time with David, what you have a sense of is just how mentally healthy he was. If you had asked me in the summer of 2008 to name the most healthy, mentally, American writer, I would have without any hesitation, said David Wallace. He just seemed like he'd gone through something when he was younger, but he seemed healed. He seemed like someone who had a wise, funny, sharp way of looking at life, which would tend to make you live longer, not less long. I was shocked. My first response was just tremendous surprise.

You saw this health in him. Is that just from your experience with him in '96, traveling for a few days, getting the first-person encounter, or was that from his work as well?

It was from both. I only knew him for those five days, and in the five days what you read us talking about is just how he'd gone a very hard time when he was in his late twenties, and had found a way to experience the world after that. That was what I had been reading in his work, and what I'd then read in his work afterwards. The person who writes a story like “Good Old Neon”, the person who writes nonfiction like “A Supposedly Fun Thing I'll Never Do Again” or “Consider the Lobster”, is not somebody who hasn't had hardships or wouldn't know how to go through it. Somebody who has, in the full way of a life, tested themselves against hardship and come out with a kind of warm comic knowledge. That was one of the things you love about his work. That's one of the things readers always feel: he has seen all the crap stuff, all the hard stuff they've seen, but he's also still incredibly aware, incredibly alive and incredibly funny.

The story you mention, “Good Old Neon” — it's gotten a lot of re-reading in the wake of Wallace's death simply because of the character it describes. There's this character that goes toward an end by his own hand in the story, and it even holds up a character called David Wallace who has avoided that. You think of other stories like “The Depressed Person”, an illustration of this phenomenon of depression that it's now revealed he suffered from himself.

There seems to be so much there than indicates David Wallace understands all these problems and has somehow transcended them. I think of that as a big paradox of his life and how he wound up. Is that the same way you think about it? There's all this understanding, but he ultimately did succumb to the same thing it seemed he had a grasp on.

I did, and when I read “Good Old Neon” when it came out in book form in 2005 — I'm not a crying reader, but that's one of the only short stories I read and cried at the end of, because of this beautiful line when the narrator becomes David and says, “David Wallace emerging from years of literally indescribable war with himself, won with considerably more intellectual firepower than he had in high school in 1982. I felt that.

That's one of the nice things of spending time with someone: I knew what he was talking about. I felt this great sense of power and health in that line. As a reader, I felt that thing of what a life is, which is that someone who is awake and aware — the kinds of people who like to read, the kinds of people who turn to books to find a little bit more about their lives — they've all gone through that kind of internal, internecine conflict. To see him saying that — I hadn't seen him, then, for almost ten years — I felt very warm for him.

Read more »

When Western tourists talk about Africa somehow it seems to me that what they really mean is East and Southern Africa, places like Namibia and Kenya and Botswana and parts of Uganda where you will find safaris and zebras and elephants and lakes in abundance.