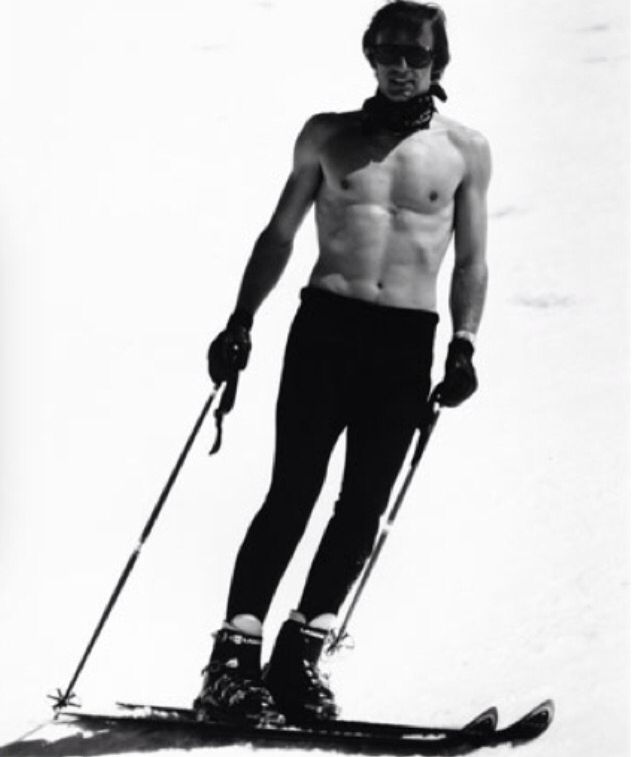

by Akim Reinhardt

“In Memory of Franz Klammer”

Franz Klammer soared

down alpine mounts,

His glory assured

by the clock’s count

The lord of Austria,

the king of the hill,

the master of the Alps,

the bringer of thrills

His grace, his speed,

defied laws of nature

His beautiful name

redefined nomenclature

Franz Klammer! Franz Klammer!

you were the best,

sparkling Olympic gold

draped ‘cross your chest.

We shall always remember

how you stormed down the mountains,

and now that you’re gone

we shall always be counting

The hours since you left,

and awaiting the day

when a soothsayer comes

and we all hear him say:

“Look up on the hill,

yonder snowy peak

A young man races hither

Come see him streak

Down the mountain side

like a B-29 bomber

Roaring like thunder,

he looks like dear Klammer!

With the wind in his face,

the mountain in his hands,

such bold, Teutonic grace,

he looks like beloved Franz!”

But alas, I do fear

such a day will not come

during my life

He was the only one

One of a kind

as down the mountains he tread–

What’s that you say?

Franz Klammer’s not dead?

But that must be a mistake,

we visited him just last week

He was rotting at the hospice,

I heard the doctor speak

About the ugly brain tumor

the gangrene and gonorrhea,

the lupus, the scurvy,

the heartburn, the diarrhea

They said he was a gonner

just a matter of time–

What? They let him out ?

He’s going home? He feels fine?!

This is ludicrous! I thought–

No, no! I’m not bitter

But between you and me,

Jean-Claude Killy was better. Read more »

Try it: try talking about the subject of reading without drifting off into how the Internet has changed the way we absorb information. I, along with the majority of people I know whose reading habits were formed long before the advent of digital magazines and newspapers, Google Books, blogs, RSS feeds, social media, and Kindle, usually feel I’m only really reading when it’s printed matter, under a reading lamp, with the screen and phone turned off. But the reality is that I do a vast amount of reading online.

Try it: try talking about the subject of reading without drifting off into how the Internet has changed the way we absorb information. I, along with the majority of people I know whose reading habits were formed long before the advent of digital magazines and newspapers, Google Books, blogs, RSS feeds, social media, and Kindle, usually feel I’m only really reading when it’s printed matter, under a reading lamp, with the screen and phone turned off. But the reality is that I do a vast amount of reading online.

Polynesia could swallow up the entire north Atlantic Ocean. It’s that big.

Polynesia could swallow up the entire north Atlantic Ocean. It’s that big.  spanning George Boole to Claude Shannon. By some measures the works of these men combine to give us our modern, programmable computer.

spanning George Boole to Claude Shannon. By some measures the works of these men combine to give us our modern, programmable computer.

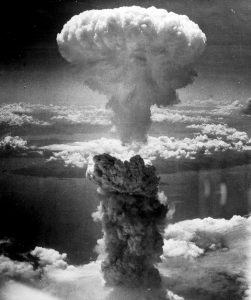

Will you know what to do when the atomic bomb drops?

Will you know what to do when the atomic bomb drops?

Even as we want to do the right thing, we may wonder if there is “really” a right thing to do. Through most of the twentieth-century most Anglo-American philosophers were some sort of subjectivist or other. Since they focused on language, the way that they tended to put it was something like this. Ethical statements look like straight-forward propositions that might be true or false, but in fact they are simply expressions or descriptions of our emotions or preferences. J.L. Mackie’s “error-theory” version, for example, implied that when I say ‘Donald Trump is a horrible person’ what I really mean is ‘I don’t like Donald Trump’. If we really believed that claims about what is right or wrong, good or bad, or just or unjust, were just subjective expressions of our own idiosyncratic emotions and desires, then our shared public discourse, and our shared public life, obviously, would look very different. One of Nietzsche’s “terrible truths” is that most of our thinking about right and wrong is just a hangover from Christianity that will eventually dissipate. We are like the cartoon character who has gone over a cliff but is not yet falling only because we haven’t looked down. Yet.

Even as we want to do the right thing, we may wonder if there is “really” a right thing to do. Through most of the twentieth-century most Anglo-American philosophers were some sort of subjectivist or other. Since they focused on language, the way that they tended to put it was something like this. Ethical statements look like straight-forward propositions that might be true or false, but in fact they are simply expressions or descriptions of our emotions or preferences. J.L. Mackie’s “error-theory” version, for example, implied that when I say ‘Donald Trump is a horrible person’ what I really mean is ‘I don’t like Donald Trump’. If we really believed that claims about what is right or wrong, good or bad, or just or unjust, were just subjective expressions of our own idiosyncratic emotions and desires, then our shared public discourse, and our shared public life, obviously, would look very different. One of Nietzsche’s “terrible truths” is that most of our thinking about right and wrong is just a hangover from Christianity that will eventually dissipate. We are like the cartoon character who has gone over a cliff but is not yet falling only because we haven’t looked down. Yet. Our first act of communication is to look in each other’s eyes, or not to. Many descriptors center subtly on the gaze: I might be shifty if I’m looking away from you too often and too purposefully, diffident if I cast downward when I ought to be looking you in the eyes, or unsettling if I never stop looking at you.

Our first act of communication is to look in each other’s eyes, or not to. Many descriptors center subtly on the gaze: I might be shifty if I’m looking away from you too often and too purposefully, diffident if I cast downward when I ought to be looking you in the eyes, or unsettling if I never stop looking at you.

In the science fiction short story “

In the science fiction short story “

The major “National-Socialist Underground” trial

The major “National-Socialist Underground” trial