by Jalees Rehman

Why do people endorse political violence such as military attacks even if such violence is detrimental to their own self-interests? The US-led war against Iraq was supported by more than 70% of Americans within days of the invasion in March 2003, and even though the support dwindled over the course of subsequent months and years as it became obvious that Iraq did not possess weapons of mass destruction (WMDs) and had not posed a major threat to the US. One could surmise that the US public had simply been misled by its government about Iraq’s weapons program and the support was thus based on a rational self-interest calculation. The fear of being eviscerated by the supposed Iraqi WMDs convinced US citizens do approve of the war. The Iraq war came at a tremendous cost: It is estimated that at least two hundred thousand Iraqi civilians have been killed, with even more deaths attributed to the subsequent humanitarian and political crises precipitated by the war. The war also resulted in the deaths of several thousand American soldiers and a far greater number of American soldiers were wounded. From an economic perspective, it is estimated that at least one trillion dollars has been added to the national debt because of the war. This war was clearly against the self-interest of the American people, especially once it became obvious that Iraq did not possess WMDs. It is therefore all the more surprising that 40% of American adults continue to believe the military invasion of Iraq was the correct decision. Is this large segment of American society acting irrationally?

The psychologist Jeremy Ginges at the New School for Social Research in New York has been researching the reasoning behind political violence for more than a decade and recently summarized his work in the paper The Moral Logic of Political Violence. He has carried out psychological experiments enrolling Palestinian refugees and Israeli settlers as well as participants from countries across the world such as Nigeria and the United States, with remarkably similar results. Read more »

It’s getting colder now in Beijing, and I can’t help but feel for the clothing left outside to dry. They had to hang through the night and on through the weak sunrise, doing their best to catch the wind before the temperature drops again. How do they feel being out there for passers-by to see, all exposed, caught up in the dust and very small toxic particles?

It’s getting colder now in Beijing, and I can’t help but feel for the clothing left outside to dry. They had to hang through the night and on through the weak sunrise, doing their best to catch the wind before the temperature drops again. How do they feel being out there for passers-by to see, all exposed, caught up in the dust and very small toxic particles?

“You start with a scarf…each 90-by-90-centimeter silk carré, printed in Lyon on twill made from thread created by the label’s own silkworms, holds a story. Since 1937, almost 2,500 original artworks have been produced, such as a 19th-century street scene from Ruedu Faubourg St.-Honore, the company’s home since 1880. The flora and fauna of Texas. A beach in Spain’s Basque country” –- this is a fragment from an advertisement article for Hermès in this month’s issue of a luxury magazine. The article is called “The Silk Road.” Does it refer to the “Silk Road” in any way that justifies the title, beyond the allure of legend? No. Does it mention that the first scarves created for this very label, in 1937, were made with raw silk from China? No. Not necessary, not relevant to the target reader. In fact, the less we mention the “East” while trying to sell such luxury designer items, the better, aiming as we are for the rich collector, the global consumer of fashion (whether belonging to the East or West) willing to spend hundreds of dollars on a small square of silk, and more likely to associate such status symbols with Western Europe rather than with the “underdeveloped,” impoverished, overpopulated, conflict-ridden East.

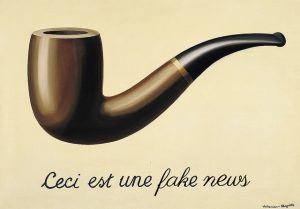

“You start with a scarf…each 90-by-90-centimeter silk carré, printed in Lyon on twill made from thread created by the label’s own silkworms, holds a story. Since 1937, almost 2,500 original artworks have been produced, such as a 19th-century street scene from Ruedu Faubourg St.-Honore, the company’s home since 1880. The flora and fauna of Texas. A beach in Spain’s Basque country” –- this is a fragment from an advertisement article for Hermès in this month’s issue of a luxury magazine. The article is called “The Silk Road.” Does it refer to the “Silk Road” in any way that justifies the title, beyond the allure of legend? No. Does it mention that the first scarves created for this very label, in 1937, were made with raw silk from China? No. Not necessary, not relevant to the target reader. In fact, the less we mention the “East” while trying to sell such luxury designer items, the better, aiming as we are for the rich collector, the global consumer of fashion (whether belonging to the East or West) willing to spend hundreds of dollars on a small square of silk, and more likely to associate such status symbols with Western Europe rather than with the “underdeveloped,” impoverished, overpopulated, conflict-ridden East. A few months back my boss and I had lunch with the person who, wearing a t-shirt that read “black death spectacle”, stood in protest in front of a painting of Emmett Till by Dana Schutz called Open Casket at the last Whitney Biennial. Shortly after his gesture another artist penned an open letter about how Schutz’s painting uses “black pain” as a medium, and how this use by non-Black artists needs to go. I’m not sure what the ethical verdict is (of whether or not Schutz made a gravely racist error), or whether the artist’s letter voiced an instance of over-reaching aesthetic censorship, nor will I make any attempt at trying to resolve that issue here; it would take far more space than what is available and is not my aim. Consider reading Aruna D’Souza’s recent book Whitewalling: Art, Race & Protest in 3 Acts for a thorough treatment (which, not so incidentally, the above mentioned protestor provided images for).

A few months back my boss and I had lunch with the person who, wearing a t-shirt that read “black death spectacle”, stood in protest in front of a painting of Emmett Till by Dana Schutz called Open Casket at the last Whitney Biennial. Shortly after his gesture another artist penned an open letter about how Schutz’s painting uses “black pain” as a medium, and how this use by non-Black artists needs to go. I’m not sure what the ethical verdict is (of whether or not Schutz made a gravely racist error), or whether the artist’s letter voiced an instance of over-reaching aesthetic censorship, nor will I make any attempt at trying to resolve that issue here; it would take far more space than what is available and is not my aim. Consider reading Aruna D’Souza’s recent book Whitewalling: Art, Race & Protest in 3 Acts for a thorough treatment (which, not so incidentally, the above mentioned protestor provided images for).

Ever since my childhood I have been excited, even electrified, by movies. In my college days in Calcutta, in search of alternate experience beyond Indian and Hollywood movies, I used to frequent the local Film Society events, showing some commercially unavailable European fare. Short of funds these Film Society outfits mainly went for movies they could procure at low cost. The East European consulates in the city were particularly generous in making available films from their countries.

Ever since my childhood I have been excited, even electrified, by movies. In my college days in Calcutta, in search of alternate experience beyond Indian and Hollywood movies, I used to frequent the local Film Society events, showing some commercially unavailable European fare. Short of funds these Film Society outfits mainly went for movies they could procure at low cost. The East European consulates in the city were particularly generous in making available films from their countries. Many decades ago, I packed my bags and left the shores of Australia and headed to the United Kingdom (UK). My secondary years of education had taught me to believe that my journey to the UK would amount to a ‘return’ to the ‘motherland’. A ‘return to the motherland’? Really? That says more about the education system I was exposed to, than just how naïve I was. However, having learned after my arrival that the UK was not, in fact, my ‘motherland’, I did discern that it had more to offer in terms of being ‘in’ the world than the distant shores of Australia, and I decided to stay. Thus, after many years resident in the UK, I considered myself as someone familiar with the country, until, that is, a change in my life circumstances provided me the opportunity to know the UK, or more specifically, England, in a totally different way.

Many decades ago, I packed my bags and left the shores of Australia and headed to the United Kingdom (UK). My secondary years of education had taught me to believe that my journey to the UK would amount to a ‘return’ to the ‘motherland’. A ‘return to the motherland’? Really? That says more about the education system I was exposed to, than just how naïve I was. However, having learned after my arrival that the UK was not, in fact, my ‘motherland’, I did discern that it had more to offer in terms of being ‘in’ the world than the distant shores of Australia, and I decided to stay. Thus, after many years resident in the UK, I considered myself as someone familiar with the country, until, that is, a change in my life circumstances provided me the opportunity to know the UK, or more specifically, England, in a totally different way.

We can agree that a verb in the present tense means that action is occurring now. What about the present progressive, which I used in the previous statement? That apparently confounds non-native English speakers because it means that an action is in the middle of happening. Friends have asked me, “What is the difference between I am playing tennis and I play tennis?” That example is actually a softball because the present progressive indicates that the first person is in the middle of playing a game and the simple present indicates the playing of the sport in general.

We can agree that a verb in the present tense means that action is occurring now. What about the present progressive, which I used in the previous statement? That apparently confounds non-native English speakers because it means that an action is in the middle of happening. Friends have asked me, “What is the difference between I am playing tennis and I play tennis?” That example is actually a softball because the present progressive indicates that the first person is in the middle of playing a game and the simple present indicates the playing of the sport in general. Before the second was defined in terms of the characteristics of the cesium atom, before leap seconds or leap days or Julian dates or the Gregorian calendar, before clocks, even before the sundial and the hourglass, there were sunrise, sunset, and shadows.

Before the second was defined in terms of the characteristics of the cesium atom, before leap seconds or leap days or Julian dates or the Gregorian calendar, before clocks, even before the sundial and the hourglass, there were sunrise, sunset, and shadows. The fall turned colors faster than ever before. The streets never saw any activity. The whole gambit of Prometheus hinged on a mere coin flip. Richard Albrook gingerly closed his book and took a look around.

The fall turned colors faster than ever before. The streets never saw any activity. The whole gambit of Prometheus hinged on a mere coin flip. Richard Albrook gingerly closed his book and took a look around.

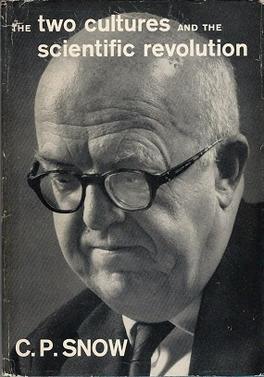

It is a commonplace to say that a divide has occurred in modern academia between the sciences and the humanities. In the anglophone world, this diagnosis is often traced back to a lecture by the British scientist-novelist Charles Snow, who pointed out in 1959 what he saw as a lamentable gap between ‘two cultures’: the literary and the scientific culture. Snow’s Rede lecture has become the main

It is a commonplace to say that a divide has occurred in modern academia between the sciences and the humanities. In the anglophone world, this diagnosis is often traced back to a lecture by the British scientist-novelist Charles Snow, who pointed out in 1959 what he saw as a lamentable gap between ‘two cultures’: the literary and the scientific culture. Snow’s Rede lecture has become the main