by Lexi Lerner

“All the greatest hits from the past forty years have the same four chords,” Axis of Awesome taught us a decade ago. “You can take those four chords, repeat them, and pump out every pop song ever.”

The band has since released multiple versions of its famous four chord medley, cataloguing more than 80 chart-toppers that follow pretty much the exact same structure. Amongst them: “Let It Be” by the Beatles, “Can You Feel the Love Tonight” by Elton John, and “Under the Bridge” by the Red Hot Chili Peppers.

While they may have lifted the veil for some lay listeners, Axis of Awesome did not invent the music theory behind the four chord song. In fact, that progression has served as the backbone of popular music since the thirties, and its prevalence has only increased with time.

Recall such recent four chorders as “Despacito” by Luis Fonsi with Daddy Yankee, “Edge of Glory” by Lady Gaga, “Someone Like You” by Adele, “Call Me Maybe” by Carly Rae Jepsen, and “We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together” by Taylor Swift. Roll your eyes if you must, but these were seminal to the Billboard Top 100 when they came out. The trend has its fingers in far more pies than just pop music; there are four chord songs as indie folk as “The Sounds of Silence” by Simon and Garfunkel, “In the Aeroplane Over the Sea” by Neutral Milk Hotel, and “Lying to You” by Keaton Henson.

Music wasn’t always like this; Brahms and Wagner and Strauss would all sob at what earns airplay these days. So when the permutations, instrumentation, length, and knowledge of music are more boundless than ever, why do we settle for the same four chords? And if most songs are built on that, what makes certain ones destined for mixtapes and wedding dances and long car rides and summer soundtracks? Why do we consider anything to be special? Read more »

Ever since my childhood I have been excited, even electrified, by movies. In my college days in Calcutta, in search of alternate experience beyond Indian and Hollywood movies, I used to frequent the local Film Society events, showing some commercially unavailable European fare. Short of funds these Film Society outfits mainly went for movies they could procure at low cost. The East European consulates in the city were particularly generous in making available films from their countries.

Ever since my childhood I have been excited, even electrified, by movies. In my college days in Calcutta, in search of alternate experience beyond Indian and Hollywood movies, I used to frequent the local Film Society events, showing some commercially unavailable European fare. Short of funds these Film Society outfits mainly went for movies they could procure at low cost. The East European consulates in the city were particularly generous in making available films from their countries. Many decades ago, I packed my bags and left the shores of Australia and headed to the United Kingdom (UK). My secondary years of education had taught me to believe that my journey to the UK would amount to a ‘return’ to the ‘motherland’. A ‘return to the motherland’? Really? That says more about the education system I was exposed to, than just how naïve I was. However, having learned after my arrival that the UK was not, in fact, my ‘motherland’, I did discern that it had more to offer in terms of being ‘in’ the world than the distant shores of Australia, and I decided to stay. Thus, after many years resident in the UK, I considered myself as someone familiar with the country, until, that is, a change in my life circumstances provided me the opportunity to know the UK, or more specifically, England, in a totally different way.

Many decades ago, I packed my bags and left the shores of Australia and headed to the United Kingdom (UK). My secondary years of education had taught me to believe that my journey to the UK would amount to a ‘return’ to the ‘motherland’. A ‘return to the motherland’? Really? That says more about the education system I was exposed to, than just how naïve I was. However, having learned after my arrival that the UK was not, in fact, my ‘motherland’, I did discern that it had more to offer in terms of being ‘in’ the world than the distant shores of Australia, and I decided to stay. Thus, after many years resident in the UK, I considered myself as someone familiar with the country, until, that is, a change in my life circumstances provided me the opportunity to know the UK, or more specifically, England, in a totally different way.

We can agree that a verb in the present tense means that action is occurring now. What about the present progressive, which I used in the previous statement? That apparently confounds non-native English speakers because it means that an action is in the middle of happening. Friends have asked me, “What is the difference between I am playing tennis and I play tennis?” That example is actually a softball because the present progressive indicates that the first person is in the middle of playing a game and the simple present indicates the playing of the sport in general.

We can agree that a verb in the present tense means that action is occurring now. What about the present progressive, which I used in the previous statement? That apparently confounds non-native English speakers because it means that an action is in the middle of happening. Friends have asked me, “What is the difference between I am playing tennis and I play tennis?” That example is actually a softball because the present progressive indicates that the first person is in the middle of playing a game and the simple present indicates the playing of the sport in general. Before the second was defined in terms of the characteristics of the cesium atom, before leap seconds or leap days or Julian dates or the Gregorian calendar, before clocks, even before the sundial and the hourglass, there were sunrise, sunset, and shadows.

Before the second was defined in terms of the characteristics of the cesium atom, before leap seconds or leap days or Julian dates or the Gregorian calendar, before clocks, even before the sundial and the hourglass, there were sunrise, sunset, and shadows. The fall turned colors faster than ever before. The streets never saw any activity. The whole gambit of Prometheus hinged on a mere coin flip. Richard Albrook gingerly closed his book and took a look around.

The fall turned colors faster than ever before. The streets never saw any activity. The whole gambit of Prometheus hinged on a mere coin flip. Richard Albrook gingerly closed his book and took a look around.

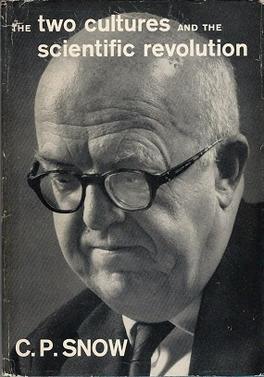

It is a commonplace to say that a divide has occurred in modern academia between the sciences and the humanities. In the anglophone world, this diagnosis is often traced back to a lecture by the British scientist-novelist Charles Snow, who pointed out in 1959 what he saw as a lamentable gap between ‘two cultures’: the literary and the scientific culture. Snow’s Rede lecture has become the main

It is a commonplace to say that a divide has occurred in modern academia between the sciences and the humanities. In the anglophone world, this diagnosis is often traced back to a lecture by the British scientist-novelist Charles Snow, who pointed out in 1959 what he saw as a lamentable gap between ‘two cultures’: the literary and the scientific culture. Snow’s Rede lecture has become the main

“Beware of literature!” This warning occurs in Jean-Paul Sartre’s 1938 novel Nausea as an entry in the diary of the narrator, Antoine Roquentin. In context, it concerns the way that literary narratives falsify our experience of events by investing them with an organization and structure that our experiences in themselves, as we live them, do not have. When Bilbo Baggins finds the ring in The Hobbit, Tolkein tells us that although Bilbo didn’t realize it at the time, this would turn out to be a turning point in his life. When married couples recall their first meeting, their account inevitably packages the event as a “beginning,” even though they may have had no inkling of this at the time.

“Beware of literature!” This warning occurs in Jean-Paul Sartre’s 1938 novel Nausea as an entry in the diary of the narrator, Antoine Roquentin. In context, it concerns the way that literary narratives falsify our experience of events by investing them with an organization and structure that our experiences in themselves, as we live them, do not have. When Bilbo Baggins finds the ring in The Hobbit, Tolkein tells us that although Bilbo didn’t realize it at the time, this would turn out to be a turning point in his life. When married couples recall their first meeting, their account inevitably packages the event as a “beginning,” even though they may have had no inkling of this at the time. Do you find this prospect upsetting? Perhaps you think it is unfair for someone to get a job without a good reason for why they deserve it rather than anyone else. Perhaps you think such a system would decrease your chances of getting the job you want. If so then you may be under the influence of the cult of excellence.

Do you find this prospect upsetting? Perhaps you think it is unfair for someone to get a job without a good reason for why they deserve it rather than anyone else. Perhaps you think such a system would decrease your chances of getting the job you want. If so then you may be under the influence of the cult of excellence.