by Michael Liss

How do you raise kids in an increasingly harsh and atonal world?

We all have our templates for seeking harmony. Mine were my own parents. They were not performing artists or even musicians; neither played an instrument (I think the kazoo doesn’t qualify), and neither could sing. But, as listeners, they were virtuosos. Classical, of course, but also big band and swing, boogie-woogie and jazz, klezmer, folk and protest songs. My father even harbored a secret passion for some pretty hardcore mountain music—the real thing, serious pickin’ and fiddlin’ without the Nashville gloss. My sister and I think he gave this up, along with drinking and smoking, when he met my mother.

Then, there was opera. I’ve written before about being tied to a chair in the Orchestra section of the old Met when my legs were still too short to make it all the way to the floor. It was all true: I saw Tosca jump off the parapet, and Madame Butterfly do herself in, and Mimi tragically pass, and Violetta tragically pass, and Radames and Aïda jointly and severally tragically pass, and Baron Scarpia and Don Giovanni not-so-tragically pass. All that passing was inescapable;  to quote Bugs Bunny in the towering “What’s Opera Doc?” (as even he passed, a victim of Elmer’s spear and magic helmet), “What did you expect in an opera, a happy ending?”

to quote Bugs Bunny in the towering “What’s Opera Doc?” (as even he passed, a victim of Elmer’s spear and magic helmet), “What did you expect in an opera, a happy ending?”

In retrospect, I should have been honored that my parents had such confidence in my emotional stability that they felt assured I could cope with all that passing. In the moment, however, I don’t think it ever entirely registered with me, especially since all the adults would then cheer wildly. Brava, she’s dead? Read more »

All this is spelt out in Morris’s 1977 book, The Beginning of the World, most recently reprinted in 2005 (in Morris’s lifetime, and presumably with his approval), and available from Amazon as a paperback or on Kindle.

All this is spelt out in Morris’s 1977 book, The Beginning of the World, most recently reprinted in 2005 (in Morris’s lifetime, and presumably with his approval), and available from Amazon as a paperback or on Kindle.

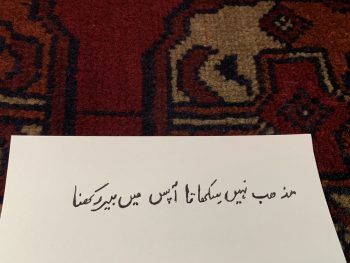

Less than a month ago, the Indian Air Force conducted airstrikes inside Pakistan. The last attack of this kind took place in 1971, before I was born, and though tensions between the two countries have never ceased, even the family’s fragmented recollections of blackouts, travel restrictions and patriotic songs on the radio had become a distant memory for me until the moment I found myself stranded in Karachi due to airspace closure and witnessed not just military crossfire but that of the media of the two countries. The outbursts on news channels, as well as social media were interspersed with slogans and songs. One Indian patriotic song in particular, a ghazal by Allama Iqbal who is known as Pakistan’s national poet, sung not only in the voices of India’s celebrity singers and sweet-faced schoolchildren, but also adapted to their military march tune, caught my attention.

Less than a month ago, the Indian Air Force conducted airstrikes inside Pakistan. The last attack of this kind took place in 1971, before I was born, and though tensions between the two countries have never ceased, even the family’s fragmented recollections of blackouts, travel restrictions and patriotic songs on the radio had become a distant memory for me until the moment I found myself stranded in Karachi due to airspace closure and witnessed not just military crossfire but that of the media of the two countries. The outbursts on news channels, as well as social media were interspersed with slogans and songs. One Indian patriotic song in particular, a ghazal by Allama Iqbal who is known as Pakistan’s national poet, sung not only in the voices of India’s celebrity singers and sweet-faced schoolchildren, but also adapted to their military march tune, caught my attention.

In this world of divisive and indeed, not infrequently, ugly politics, particularly in the United States under the present administration, and the British pursuit of an exit from the European Union, any opportunity for finding relief from the ‘angst’ of day to day politics is to be welcomed. The reading of Peter Wohlleben’s The Mysteries of Nature Trilogy: The Hidden Life of Trees, The Secret Network of Nature and The Inner Life of Animals provided me with such an opportunity.

In this world of divisive and indeed, not infrequently, ugly politics, particularly in the United States under the present administration, and the British pursuit of an exit from the European Union, any opportunity for finding relief from the ‘angst’ of day to day politics is to be welcomed. The reading of Peter Wohlleben’s The Mysteries of Nature Trilogy: The Hidden Life of Trees, The Secret Network of Nature and The Inner Life of Animals provided me with such an opportunity.

In the next couple of months two of the largest democracies in the world—India and Indonesia—will have their national elections. At a time when democracy is under considerable pressure everywhere, the electoral and general democratic outcome in these two countries containing in total more than one and a half billion people (more than one and a half times the population in democratic West plus Japan and Australia) will be closely observed.

In the next couple of months two of the largest democracies in the world—India and Indonesia—will have their national elections. At a time when democracy is under considerable pressure everywhere, the electoral and general democratic outcome in these two countries containing in total more than one and a half billion people (more than one and a half times the population in democratic West plus Japan and Australia) will be closely observed.

There is a sense in certain quarters that both experimental and theoretical fundamental physics are at an impasse. Other branches of physics like condensed matter physics and fluid dynamics are thriving, but since the composition and existence of the fundamental basis of matter, the origins of the universe and the unity of quantum mechanics with general relativity have long since been held to be foundational matters in physics, this lack of progress rightly bothers its practitioners.

There is a sense in certain quarters that both experimental and theoretical fundamental physics are at an impasse. Other branches of physics like condensed matter physics and fluid dynamics are thriving, but since the composition and existence of the fundamental basis of matter, the origins of the universe and the unity of quantum mechanics with general relativity have long since been held to be foundational matters in physics, this lack of progress rightly bothers its practitioners.

I was struck by a sentence in Susan Orlean’s The Library Book: “If nothing lasts, nothing matters.” This line was part of a discussion of memory, the fear of being forgotten, and the value of passing things on to future generations. I share a passion for the idea of continuity between generations (and I highly recommend Orlean’s book), but ultimately I don’t think that something has to last to matter. Alan Watts, in his book This Is It, says that “This—the immediate, everyday, and present experience—is IT, the entire and ultimate point for the existence of a universe.” It’s not about connecting with anything but what’s here in front of me now. (Easier said than done, of course.)

I was struck by a sentence in Susan Orlean’s The Library Book: “If nothing lasts, nothing matters.” This line was part of a discussion of memory, the fear of being forgotten, and the value of passing things on to future generations. I share a passion for the idea of continuity between generations (and I highly recommend Orlean’s book), but ultimately I don’t think that something has to last to matter. Alan Watts, in his book This Is It, says that “This—the immediate, everyday, and present experience—is IT, the entire and ultimate point for the existence of a universe.” It’s not about connecting with anything but what’s here in front of me now. (Easier said than done, of course.) I teach two kinds of group exercise classes, and part of the certification processes for both disciplines devoted no small amount of attention to how to speak to your minions, uh, students.

I teach two kinds of group exercise classes, and part of the certification processes for both disciplines devoted no small amount of attention to how to speak to your minions, uh, students.