by Adele A Wilby

There is a great deal of literature available on the experiences of the horrors, suffering and the injustice that the Jewish people experienced during World War II. Bart Van Es’s The Cut Out Girl adds to that literature.

There is a great deal of literature available on the experiences of the horrors, suffering and the injustice that the Jewish people experienced during World War II. Bart Van Es’s The Cut Out Girl adds to that literature.

Bart Van Es’s The Cut-Out Girl is the winner of the 2018 Costa literary prize. It is an admirable winner: the story of Lien de Jong, and how she experienced her childhood as one of the Netherlands’ 4000 ‘hidden’ Jewish children during the Nazi occupation of the country in World War II, and her life thereafter. Lien and her immediate family were part of the 18,000 Jews who resided in The Hague in 1940, out of which only 2,000 survived the war.

The book offers revelatory insights into the precarious existence of a Jewish child constantly exposed to the danger of round-ups by Nazi troops and the possibility of betrayal of her location by local Nazi sympathisers. Inevitably her story is interconnected with the families who provided her refuge, in particular the Van Es family.

Had Oxford academic Bart Van Es not been curious about the ‘lost’ member of his family, Lien, it is doubtful that her story would ever have come to light, and the experiences of a Jewish child caught up in a struggle to survive would have been lost to the world. Van Es’s journey of discovery to learn of the ‘lost’ ‘family’ child not only leads to reconciliation with the descendants of the Van Eses who provided the refuge, but to closure for both Lien and the Van Es family saga. Read more »

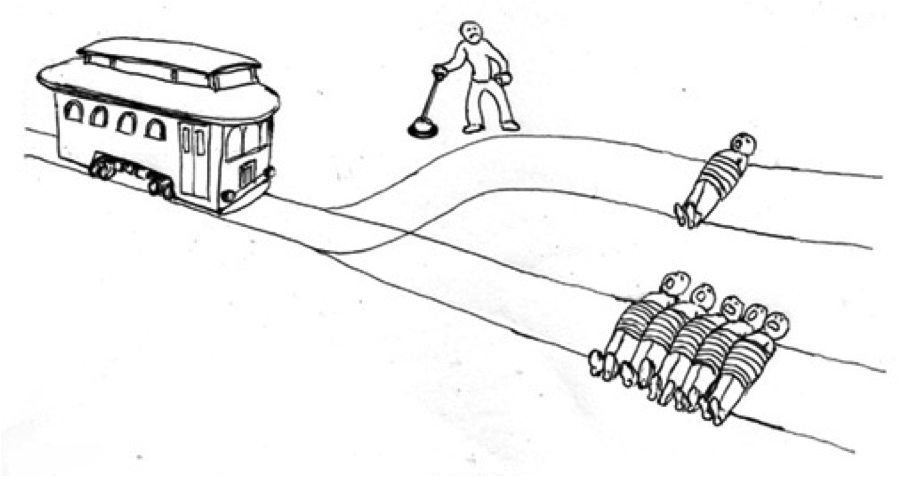

In “The Moral Landscape: How Science Can Determine Human Values” Sam Harris argues that the morally right thing to do is whatever maximizes the welfare or flourishing of human beings. Science “determines human values”, he says, by clarifying what that welfare or flourishing consists of exactly. In an early footnote he complains that “Many of my critics fault me for not engaging more directly with the academic literature on moral philosophy.” But he did not do so, he explains, for two reasons. One is that he did not arrive at his position by reading philosophy, he just came up with it, all on his own, from scratch. The second is because he “is convinced that every appearance of terms like…’deontology’”, etc. “increases the amount of boredom in the universe.”

In “The Moral Landscape: How Science Can Determine Human Values” Sam Harris argues that the morally right thing to do is whatever maximizes the welfare or flourishing of human beings. Science “determines human values”, he says, by clarifying what that welfare or flourishing consists of exactly. In an early footnote he complains that “Many of my critics fault me for not engaging more directly with the academic literature on moral philosophy.” But he did not do so, he explains, for two reasons. One is that he did not arrive at his position by reading philosophy, he just came up with it, all on his own, from scratch. The second is because he “is convinced that every appearance of terms like…’deontology’”, etc. “increases the amount of boredom in the universe.”

A British friend of mine once told me that when he feels stressed he often turns to re-reading R.K. Narayan’s stories about Malgudi, the fictional placid small town in south India. Much earlier, in the 1930’s, a fellow-Britisher, the writer Graham Greene, had discovered Narayan and became his life-long friend, mentor, agent for the wider literary world, and even occasional proof-reader. He found a kind of ‘sadness and beauty’ in Narayan’s simple depiction of the idiosyncrasies and disappointments of ordinary lives which he imbues with a touching sense of gentle irony and compassion.

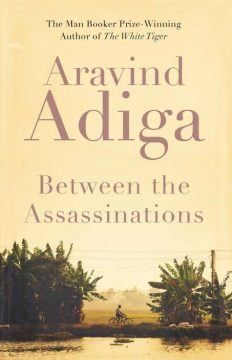

A British friend of mine once told me that when he feels stressed he often turns to re-reading R.K. Narayan’s stories about Malgudi, the fictional placid small town in south India. Much earlier, in the 1930’s, a fellow-Britisher, the writer Graham Greene, had discovered Narayan and became his life-long friend, mentor, agent for the wider literary world, and even occasional proof-reader. He found a kind of ‘sadness and beauty’ in Narayan’s simple depiction of the idiosyncrasies and disappointments of ordinary lives which he imbues with a touching sense of gentle irony and compassion. I shall start with the third, titled Between the Assassinations by Aravind Adiga, which is probably the furthest of the three in terms of dissonance from the life in Malgudi. Here we can definitely say: Toto, we are not in Malgudi anymore. The assassinations referred to are those of Indira Gandhi in 1984 and of her son, Rajiv Gandhi, in 1991, but in the book except for merely as a time-marker of those 7 years, they do not play any direct role. Adiga came to be widely noted after he won the Booker Prize for his short novel The White Tiger, a book of stridently raging fury at the crushing inequalities and depravity arising from India’s roaring economic growth and somewhat cardboard characters through which they are played out, a book I did not particularly like. Adiga wrote Between the Assassinations earlier but published it after The White Tiger. Here the fury is less strident, there is more nuance and variety in the characters, and along with aching sympathy there is all-enveloping hopelessness. Here is a typical scene: a lowly cart-rickshaw puller, straining hard going uphill with a heavy load, exhausted by the heat and humiliation and a painful neck, stops his cart in the middle of the busy road, shakes his fist in a futile gesture at the passing, honking traffic and shouts: ‘Don’t you see something is wrong with this world?’

I shall start with the third, titled Between the Assassinations by Aravind Adiga, which is probably the furthest of the three in terms of dissonance from the life in Malgudi. Here we can definitely say: Toto, we are not in Malgudi anymore. The assassinations referred to are those of Indira Gandhi in 1984 and of her son, Rajiv Gandhi, in 1991, but in the book except for merely as a time-marker of those 7 years, they do not play any direct role. Adiga came to be widely noted after he won the Booker Prize for his short novel The White Tiger, a book of stridently raging fury at the crushing inequalities and depravity arising from India’s roaring economic growth and somewhat cardboard characters through which they are played out, a book I did not particularly like. Adiga wrote Between the Assassinations earlier but published it after The White Tiger. Here the fury is less strident, there is more nuance and variety in the characters, and along with aching sympathy there is all-enveloping hopelessness. Here is a typical scene: a lowly cart-rickshaw puller, straining hard going uphill with a heavy load, exhausted by the heat and humiliation and a painful neck, stops his cart in the middle of the busy road, shakes his fist in a futile gesture at the passing, honking traffic and shouts: ‘Don’t you see something is wrong with this world?’

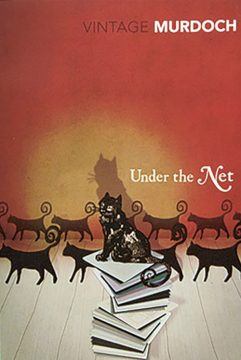

Mother’s friend departed after their weekly get-together for tea, cakes and gossip, but she forgot to take her book. It was a slim hardback with the blue and yellow banded cover of a subscription book club. It lay on the arm of the sofa for ten minutes and then, before anybody noticed, it vanished – relocated to my bedroom. I was fifteen, and this would be the first adult novel I had ever read. Its title was Under the Net by Iris Murdoch. Iris was my “first” – first adult novelist and first woman writer, and she has remained fixed in my affections over the decades. Under the Net was also Murdoch’s first novel, published in 1954. I was so naively charmed that I made a precocious promise to myself to reread it fifteen years later to see if its appeal lasted. I already knew that in the coming years I would not be rereading my previous favourites, my childhood book collections of Just William, Biggles, Billy Bunter and John Carter’s adventures on Mars. Unlike them, Under the Net had mysteries and ideas I did not yet fathom, but would need to discover.

Mother’s friend departed after their weekly get-together for tea, cakes and gossip, but she forgot to take her book. It was a slim hardback with the blue and yellow banded cover of a subscription book club. It lay on the arm of the sofa for ten minutes and then, before anybody noticed, it vanished – relocated to my bedroom. I was fifteen, and this would be the first adult novel I had ever read. Its title was Under the Net by Iris Murdoch. Iris was my “first” – first adult novelist and first woman writer, and she has remained fixed in my affections over the decades. Under the Net was also Murdoch’s first novel, published in 1954. I was so naively charmed that I made a precocious promise to myself to reread it fifteen years later to see if its appeal lasted. I already knew that in the coming years I would not be rereading my previous favourites, my childhood book collections of Just William, Biggles, Billy Bunter and John Carter’s adventures on Mars. Unlike them, Under the Net had mysteries and ideas I did not yet fathom, but would need to discover.

Nature has filled the world with “endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful,” in the words of Charles Darwin. We humans, faced with this abundance and variety of creatures, have used our imagination to the full in giving them descriptive and often evocative names. Some animal names are fairly straightforward; the name big hairy armadillo lacks nuance, although it makes up in charm what it lacks in subtlety. In other cases, though, we’ve come up with epithets that would make a poet proud: the tawny-crowned greenlet, the sharp-shinned hawk, the pricklenape lizards.

Nature has filled the world with “endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful,” in the words of Charles Darwin. We humans, faced with this abundance and variety of creatures, have used our imagination to the full in giving them descriptive and often evocative names. Some animal names are fairly straightforward; the name big hairy armadillo lacks nuance, although it makes up in charm what it lacks in subtlety. In other cases, though, we’ve come up with epithets that would make a poet proud: the tawny-crowned greenlet, the sharp-shinned hawk, the pricklenape lizards.

Whether we’re glancing through a play from high school before donating it or wandering through an antique shop, sometimes we see a word that doesn’t look quite right. Sometimes, misspelled words are a result of advertising campaigns, and other times they are alternate spellings in English. We all know English has some demented rules of orthography (even the word “orthography” can inspire chuckles; “proper writing” in English? Is that a joke?). You’re not alone if you have to remind yourself about “i before e except after c” and its numerous exceptions.

Whether we’re glancing through a play from high school before donating it or wandering through an antique shop, sometimes we see a word that doesn’t look quite right. Sometimes, misspelled words are a result of advertising campaigns, and other times they are alternate spellings in English. We all know English has some demented rules of orthography (even the word “orthography” can inspire chuckles; “proper writing” in English? Is that a joke?). You’re not alone if you have to remind yourself about “i before e except after c” and its numerous exceptions.