by Dave Maier

Here we have either a) a holiday gift guide; b) just another ordinary book roundup; or c) a bunch of mini-reviews each of which just didn’t have the oomph to deserve its own post. Answer provided below!

First up:

Theodore M. Bernstein – Miss Thistlebottom’s Hobgoblins: The Careful Writer’s Guide to the Taboos, Bugbears, and Outmoded Rules of English Usage (1971)

Theodore M. Bernstein – Miss Thistlebottom’s Hobgoblins: The Careful Writer’s Guide to the Taboos, Bugbears, and Outmoded Rules of English Usage (1971)

Rodney Huddleston and Geoffrey K. Pullum – A Student’s Introduction to English Grammar (2005)

I rarely read Columbia’s alumni magazine, but I did happen to see an interesting exchange (“Verbal Dispute”) in the Feedback section of the Fall 2019 issue. Apparently the cover of the previous issue had read “About 8 million tons of plastic ends up in the ocean every year,” and, perhaps not surprisingly, numerous quasi-literate chuckleheads had conveyed their righteous outrage at the offense to grammar so publicly displayed. Two are quoted; one explains to us that “‘Tons’ is a plural subject that takes the plural verb ‘end up,” continuing witheringly, “Are you a native English speaker? From California? [ooh, snap!] Are you intent on sabotaging Columbia or unqualified and irresponsible?” and so on.

The editor’s response is at once coolly civil and delectably devastating.

While it is certainly true that “end up” is the standard plural form, a singular verb is often used instead when the subject is a phrase that can be viewed as a single unit. This is particularly common when the subject is an expression of quantity or measure, as in “eight million tons.”

He then provides supporting examples from the above authors. I’ve listed the Huddleston and Pullum book I own; the actual quote is from their previous work, The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language (2002), on which the former is based. Their examples are simply brutal. (Try to say these sentences out loud with the plural form of the verb; you won’t even be able to.)

Twenty dollars seems a ridiculous amount to pay to go to the movies. Five miles is rather more than I want to walk this afternoon. Three eggs is plenty. [Yow.]

From Bernstein’s book (which I immediately ordered upon reading this):

You would not [or, you know, maybe you would, if you were a quasi-literate chucklehead] write “Three inches of snow have fallen,” because you are not thinking of individual inches; you are thinking of a quantity of snow that accumulates to that depth. Likewise you would not write “About $10,000 were added to the cost of the project,” because again you are thinking of a sum of money, not of individual dollars.

I’m tempted to quote as well what Huddleston and Pullum say about singular uses of “they,” because it also combines definitive analysis with deliciously polite snark, but let’s move on. Read more »

Godfrey points the Land Rover toward Ngorongoro Crater. The road is fine to lull the unwary, but before you know it there is one lane, then no tarmac, then mud and potholes and empty hills.

Godfrey points the Land Rover toward Ngorongoro Crater. The road is fine to lull the unwary, but before you know it there is one lane, then no tarmac, then mud and potholes and empty hills.

Europeans spent 400 years killing, raping, lying to, and robbing Indigenous Americans. And then, when they’d taken most everything they wanted, they turned Native peoples into tokens, costumes, mascots, and fashion accessories. Like most fashion trends, it’s gone in cycles.

Europeans spent 400 years killing, raping, lying to, and robbing Indigenous Americans. And then, when they’d taken most everything they wanted, they turned Native peoples into tokens, costumes, mascots, and fashion accessories. Like most fashion trends, it’s gone in cycles.

Childrearing practices in the United States underwent a radical alteration during a period from the last decade of the nineteenth century through the first few decades of the twentieth. In 1929, psychologists William Blatz and Helen Bott looked back on the changes they credited to Dr. Luther Emmett Holt, whose childcare manual was first published in 1894 and continued to come out in new editions every few years:

Childrearing practices in the United States underwent a radical alteration during a period from the last decade of the nineteenth century through the first few decades of the twentieth. In 1929, psychologists William Blatz and Helen Bott looked back on the changes they credited to Dr. Luther Emmett Holt, whose childcare manual was first published in 1894 and continued to come out in new editions every few years: I recently read Jill Lepore’s

I recently read Jill Lepore’s  At the heart of French existentialism – and especially the version associated with its most famous representative, Jean Paul Sartre – was the notion of radical freedom. On this view, when we choose, we choose our values and thus what kind of person we are going to be. Nothing can prescribe to us what we ought to value, and the responsibility of freedom is to accept this fact of the human condition without falling into the ‘bad faith’ which would deny it. The moment of existentialism may have passed, but the view that we are radical choosers of our values persists in many quarters, and so I want to consider how well this idea holds up, and what an alternative to it might look like.

At the heart of French existentialism – and especially the version associated with its most famous representative, Jean Paul Sartre – was the notion of radical freedom. On this view, when we choose, we choose our values and thus what kind of person we are going to be. Nothing can prescribe to us what we ought to value, and the responsibility of freedom is to accept this fact of the human condition without falling into the ‘bad faith’ which would deny it. The moment of existentialism may have passed, but the view that we are radical choosers of our values persists in many quarters, and so I want to consider how well this idea holds up, and what an alternative to it might look like. Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Microsoft, and Google, often referred to as Big Tech, know more about you than your closest friends and family. They know who you are talking to and what you are talking about, what you are buying or are thinking of buying, how much money you have, and what your fears and desires are. What a few years ago may have sounded like a dystopic vision, is today a reality of our online life (our ‘onlife’). In this setting, even Facebook’s plans of introducing their own currency, Libra, does not seem out of the ordinary.

Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Microsoft, and Google, often referred to as Big Tech, know more about you than your closest friends and family. They know who you are talking to and what you are talking about, what you are buying or are thinking of buying, how much money you have, and what your fears and desires are. What a few years ago may have sounded like a dystopic vision, is today a reality of our online life (our ‘onlife’). In this setting, even Facebook’s plans of introducing their own currency, Libra, does not seem out of the ordinary.

A long time ago, on a mountainside in Liechtenstein, I tuned my transistor radio to the Deutschlandfunk, one of neighboring Germany’s state radio stations whose broadcast range leaked into that tiny country. This is what I heard:

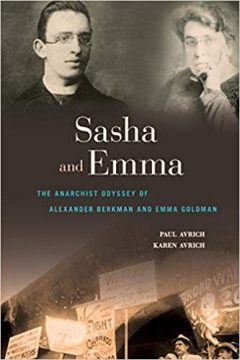

A long time ago, on a mountainside in Liechtenstein, I tuned my transistor radio to the Deutschlandfunk, one of neighboring Germany’s state radio stations whose broadcast range leaked into that tiny country. This is what I heard: Biographies frequently provide us with insights into individual characters in a way that autobiographies might not: the third person narrator offers the prospect of greater ‘objectivity’ when evaluating and narrating information and events and circumstances. And so it is with Paul Avrich and Karen Avrich’s Sasha and Emma: The Anarchist Odyssey of Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman,and Katie Kirkpatrick’s Becoming Beauvoir: A Life.These two books provide a wealth of knowledge on the political and philosophical thinking that engaged the brilliant minds of two significant women of the twentieth century: Emma Goldman and Simone Beauvoir.

Biographies frequently provide us with insights into individual characters in a way that autobiographies might not: the third person narrator offers the prospect of greater ‘objectivity’ when evaluating and narrating information and events and circumstances. And so it is with Paul Avrich and Karen Avrich’s Sasha and Emma: The Anarchist Odyssey of Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman,and Katie Kirkpatrick’s Becoming Beauvoir: A Life.These two books provide a wealth of knowledge on the political and philosophical thinking that engaged the brilliant minds of two significant women of the twentieth century: Emma Goldman and Simone Beauvoir. The life trajectories of the two women could not have been more different: Goldman was a Jewish Russian émigré to the United States; she learned her politics through experience and in that process clarified her political thinking on anarchism, and her life was lived humbly. Beauvoir on the other hand, was from a bourgeois Catholic family and benefited from a formal education and she lived life relatively comfortably. However, despite their divergent lifestyles and politics, similarities can be drawn between their thinking on women, love and freedom.

The life trajectories of the two women could not have been more different: Goldman was a Jewish Russian émigré to the United States; she learned her politics through experience and in that process clarified her political thinking on anarchism, and her life was lived humbly. Beauvoir on the other hand, was from a bourgeois Catholic family and benefited from a formal education and she lived life relatively comfortably. However, despite their divergent lifestyles and politics, similarities can be drawn between their thinking on women, love and freedom.

Suppose you had some undeniable proof of the Everettian or Many-Worlds Interpretation (MWI) of quantum mechanics. You would know, then, that there are very many, uncountably many, parallel worlds and that in very many of these there are many, many nearly identical versions of you – as well as many less-closely related “you’s” in still other worlds. Would this change the way you think about yourself and your life? How? Would you take the decisions that you make more or less seriously?

Suppose you had some undeniable proof of the Everettian or Many-Worlds Interpretation (MWI) of quantum mechanics. You would know, then, that there are very many, uncountably many, parallel worlds and that in very many of these there are many, many nearly identical versions of you – as well as many less-closely related “you’s” in still other worlds. Would this change the way you think about yourself and your life? How? Would you take the decisions that you make more or less seriously?