by Claire Chambers

This has been a terrible year with almost no redeeming features. I have written elsewhere about Covid-19’s hardships, both personal and political. Today, with a vaccine on the horizon and Trump defeated, I want to find some other crumbs of comfort that, as with Hansel and Gretel, might take us somewhere.

I am privileged to live with my husband Rob and two sons in our own house with a garden, and to hold down a lecturing job which is pretty secure. Rob is even more financially stable in his career, working as he does in a growth industry this pestilent year: he’s a family doctor.

But of course being a GP has brought its own share of unexpected stresses recently. In March when the UK government spectacularly failed to get PPE for medical professionals and disaster capitalists were circling, Rob bought some pyjamas from Marks and Spencer for turning into improvised surgical scrubs. He even fashioned his own visor using a piece of sponge, some plexiglass, and a coat hanger. Although he never had to use it, I won’t forget that time of helpless, abandoned terror.

Nigerian-American author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie posted a microblog to Instagram early into this crisis about her fears around the pandemic. When I read these terse words, I nodded vigorously:

My husband is a doctor and each morning when he leaves for work, I worry. My throat itches and I worry. On Facetime I watch my elderly parents. I admonish them gently: Don’t let people come to the house. Don’t read the rubbish news on WhatsApp.

Out of the two vulnerable parents Adichie was worrying about in this essay from April, it is poignant to realize that her father was to die just two months later. Read more »

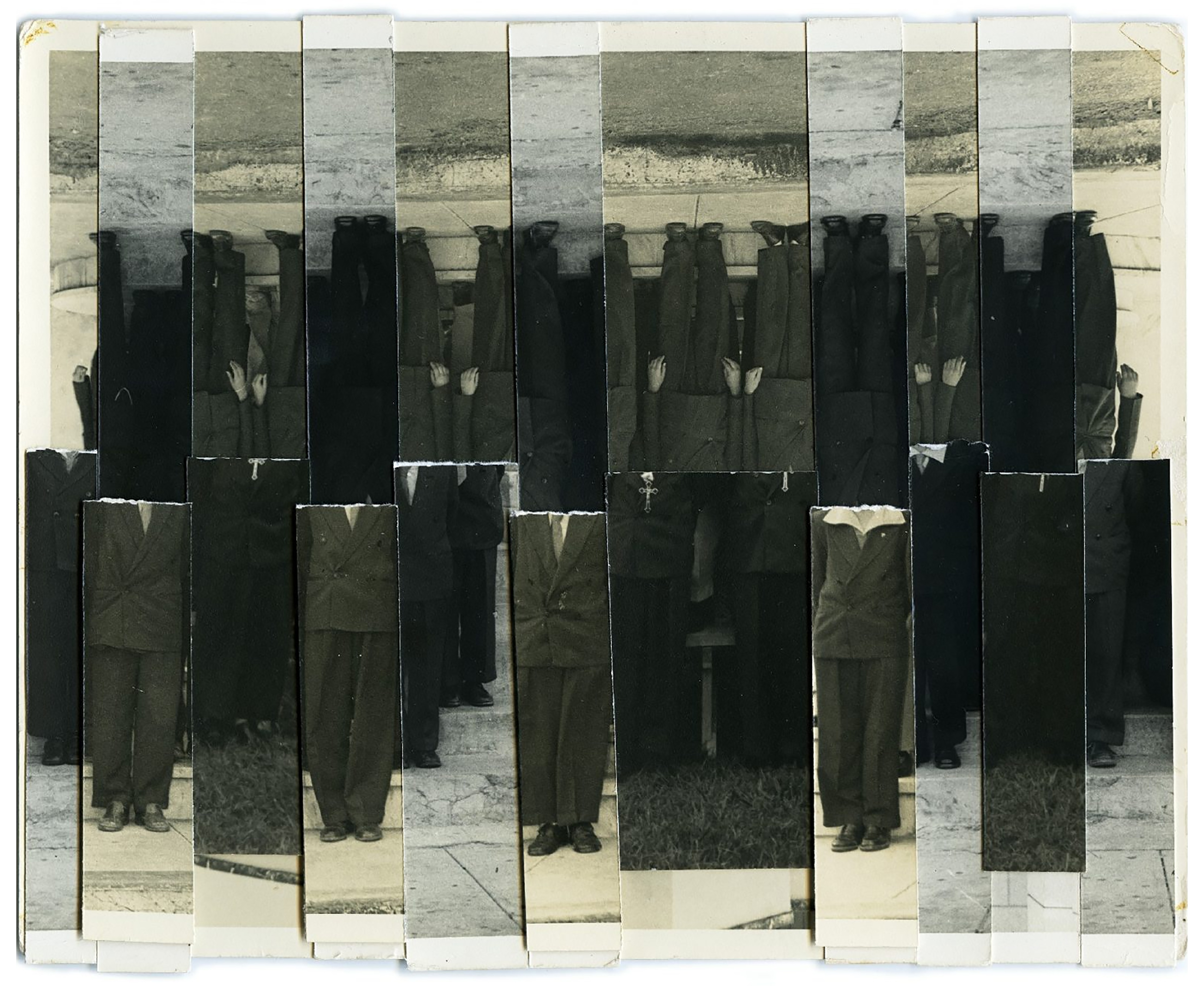

Not long ago there was an article circulating on Facebook about ‘Hating the English’, originally published in a large circulation newspaper. The Irish author says something to the effect that once she thought it was just a few bad ones etc., but now she hates the lot of them. It’s been stimulated, I think, by the repulsive English nationalism that has been raising its head since Brexit, plus the usual ignorance about Ireland, Irish history and Irish interests on the part of your typical ‘Brit’. It’s not a very good piece of writing, and it has a rather slight idea in it. I’d ignore it but for the ‘likes’ and positive comments it’s received, particularly from ‘leftists’. It’s an example of what we could call ‘bloc thinking’ – the emotionally satisfying but futile consignment of entire masses of people into categories of nice and nasty.

Not long ago there was an article circulating on Facebook about ‘Hating the English’, originally published in a large circulation newspaper. The Irish author says something to the effect that once she thought it was just a few bad ones etc., but now she hates the lot of them. It’s been stimulated, I think, by the repulsive English nationalism that has been raising its head since Brexit, plus the usual ignorance about Ireland, Irish history and Irish interests on the part of your typical ‘Brit’. It’s not a very good piece of writing, and it has a rather slight idea in it. I’d ignore it but for the ‘likes’ and positive comments it’s received, particularly from ‘leftists’. It’s an example of what we could call ‘bloc thinking’ – the emotionally satisfying but futile consignment of entire masses of people into categories of nice and nasty.

According to Donald Trump, in

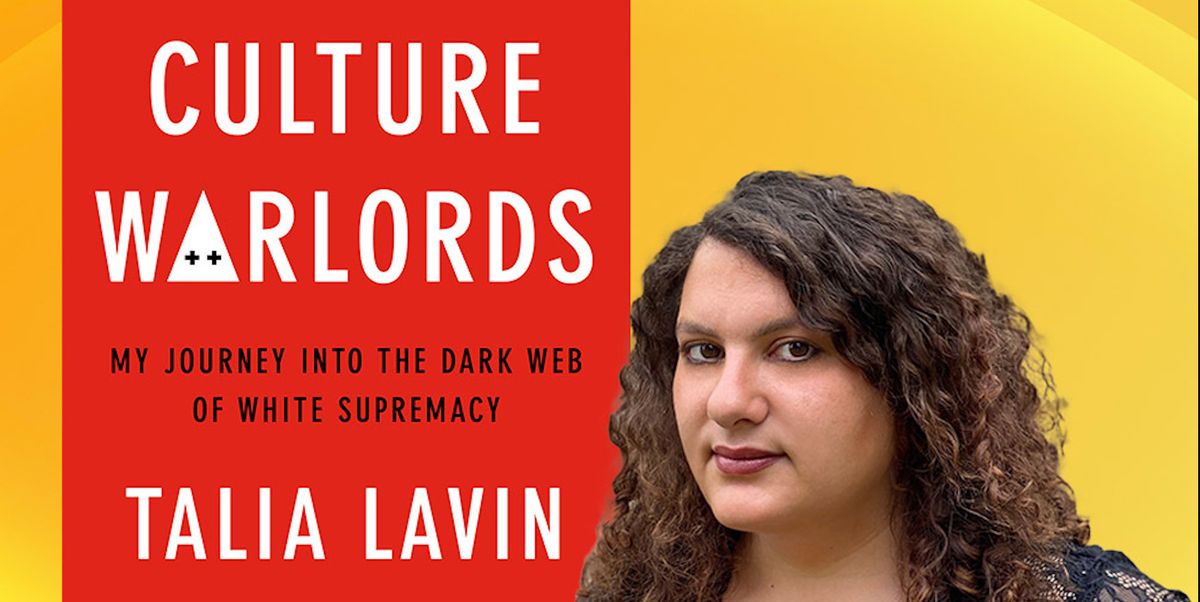

According to Donald Trump, in  Recent protests in the US by Trump supporters since the election of Joe Biden, highlight just how political ideologies have the potential to tear seemingly ‘stable’ societies apart. A political divide however cannot always be seen as a clear-cut contradiction between the right and the left, as, for example, the way Trump supporters might assert; Biden, and Democrats more broadly, could hardly be seen to represent the left. Likewise, the right has it shades of commitment to conservatism. However, Trump’s 70 million supporters represent a congealing of far-right politics in America identifiable by the policies articulated by Trump that they endorse: anti- immigration, racism, a resurgent nationalism. While there is little doubt that such policies have been magical music to the ears of many right wingers, for others Trump and the Republican Party do not go far enough, and it is these extreme right-wing groups that are the subject of Talia Lavin’s book Culture Warlords: My Journey into the Dark Web of White Supremacists.

Recent protests in the US by Trump supporters since the election of Joe Biden, highlight just how political ideologies have the potential to tear seemingly ‘stable’ societies apart. A political divide however cannot always be seen as a clear-cut contradiction between the right and the left, as, for example, the way Trump supporters might assert; Biden, and Democrats more broadly, could hardly be seen to represent the left. Likewise, the right has it shades of commitment to conservatism. However, Trump’s 70 million supporters represent a congealing of far-right politics in America identifiable by the policies articulated by Trump that they endorse: anti- immigration, racism, a resurgent nationalism. While there is little doubt that such policies have been magical music to the ears of many right wingers, for others Trump and the Republican Party do not go far enough, and it is these extreme right-wing groups that are the subject of Talia Lavin’s book Culture Warlords: My Journey into the Dark Web of White Supremacists.

When I was seventeen years old, I took my first college science course, a summer class in astronomy for non-majors. The professor narrated his wild claims in an amused deadpan, calmly showing us how to reconstruct the life cycle of stars, and how to estimate the age of the universe. This course was at the University of Iowa, and I imagine that the professor was accustomed to intermittent resistance from students like me, whose rural, religious upbringing led them—led me—to challenge his claims. Yet I often found myself at a loss. The professor used a soft sell, and his claims seemed somewhere beyond the realm of mere politics or belief. Sure, I could spot a few gaps in his vision (he batted away my psychoanalytic interpretation of the Big Bang by saying he had never heard of Freud), but I envied him. I wished that my own positions were so easy to defend.

When I was seventeen years old, I took my first college science course, a summer class in astronomy for non-majors. The professor narrated his wild claims in an amused deadpan, calmly showing us how to reconstruct the life cycle of stars, and how to estimate the age of the universe. This course was at the University of Iowa, and I imagine that the professor was accustomed to intermittent resistance from students like me, whose rural, religious upbringing led them—led me—to challenge his claims. Yet I often found myself at a loss. The professor used a soft sell, and his claims seemed somewhere beyond the realm of mere politics or belief. Sure, I could spot a few gaps in his vision (he batted away my psychoanalytic interpretation of the Big Bang by saying he had never heard of Freud), but I envied him. I wished that my own positions were so easy to defend. Cosmology is a young science. Maybe the youngest. Some people say it started in the 1920’s when these little glowing clouds visible at certain points in the sky were found, by better and better telescopes, to be composed of billions and billions of stars, just like our own galaxy – the Milky Way – and it was then discovered that no matter what direction you looked they were all rushing away from us. More than one cosmologist has wondered if these galaxies know something that you and I don’t.

Cosmology is a young science. Maybe the youngest. Some people say it started in the 1920’s when these little glowing clouds visible at certain points in the sky were found, by better and better telescopes, to be composed of billions and billions of stars, just like our own galaxy – the Milky Way – and it was then discovered that no matter what direction you looked they were all rushing away from us. More than one cosmologist has wondered if these galaxies know something that you and I don’t. Many decades back when I was teaching at MIT, a senior colleague of mine, Paul Rosenstein-Rodan, a famous development economist, asked me at the beginning of our many long conversations what my politics was like. I said “Left of center, though many Americans may consider it too far left while several of my Marxist friends in India do not consider it left enough”. As someone from ‘old Europe’ he understood, and immediately put his hand on his heart and said “My heart too is located slightly left of center”. A 2015 study by psychologist Jose Duarte and his co-authors found that 58 to 66 per cent of social scientists in the US are ‘liberal’ (an American word, which unlike in Europe or India, may often mean ‘left of center’), and only 5 to 8 per cent are conservative. If anything, social scientists in the rest of the world are on average probably somewhat to the left of their American counterparts. If that is the case, for the world in general social democracy is likely to be an important, though not always decisive, ingredient of their ideology. In European politics and intellectual circles there was a time when social democrats were considered the main enemy of the communists, at least in their rivalry to get the attention of working classes, but now with the fading away of old-style communists, social democrats have a larger tent, which includes some socialists of yesteryear as well as liberals, besieged as they both now are by right-wing populists.

Many decades back when I was teaching at MIT, a senior colleague of mine, Paul Rosenstein-Rodan, a famous development economist, asked me at the beginning of our many long conversations what my politics was like. I said “Left of center, though many Americans may consider it too far left while several of my Marxist friends in India do not consider it left enough”. As someone from ‘old Europe’ he understood, and immediately put his hand on his heart and said “My heart too is located slightly left of center”. A 2015 study by psychologist Jose Duarte and his co-authors found that 58 to 66 per cent of social scientists in the US are ‘liberal’ (an American word, which unlike in Europe or India, may often mean ‘left of center’), and only 5 to 8 per cent are conservative. If anything, social scientists in the rest of the world are on average probably somewhat to the left of their American counterparts. If that is the case, for the world in general social democracy is likely to be an important, though not always decisive, ingredient of their ideology. In European politics and intellectual circles there was a time when social democrats were considered the main enemy of the communists, at least in their rivalry to get the attention of working classes, but now with the fading away of old-style communists, social democrats have a larger tent, which includes some socialists of yesteryear as well as liberals, besieged as they both now are by right-wing populists.

I’m disappointed in my columns so far. Not to say that they’ve been completely without value; I’ve managed to turn out some decent pieces and some kind readers have taken the time to tell me as much. But, taken together, my output exhibits a fault that I had sought to avoid from the outset. It has been far too occasional, too reactive, too of the moment in an extended, torturous moment of which I very much do not wish to be. There are exculpatory circumstances, of course. These are difficult times, and we are weak and vulnerable beings, and I am nothing if not an entrenched doom-scroller with a tendency for global anxiety. This is not an apology, because a core tenet of my approach to writing is a complete disregard for my audience. You’re all lovely people, I’m sure, but in order to write I have to provisionally discount your existence. This is, rather, a confession to the only person whose opinion matters to me as a writer. And that would be myself.

I’m disappointed in my columns so far. Not to say that they’ve been completely without value; I’ve managed to turn out some decent pieces and some kind readers have taken the time to tell me as much. But, taken together, my output exhibits a fault that I had sought to avoid from the outset. It has been far too occasional, too reactive, too of the moment in an extended, torturous moment of which I very much do not wish to be. There are exculpatory circumstances, of course. These are difficult times, and we are weak and vulnerable beings, and I am nothing if not an entrenched doom-scroller with a tendency for global anxiety. This is not an apology, because a core tenet of my approach to writing is a complete disregard for my audience. You’re all lovely people, I’m sure, but in order to write I have to provisionally discount your existence. This is, rather, a confession to the only person whose opinion matters to me as a writer. And that would be myself.

Ariana Reines and Terry Tempest Williams, writers one would never expect to be buddies, but who bonded at Harvard Divinity School, are having a public Zoom discussion in order to sell books. It’s a lovely, friendly discussion, but I’m shocked, shocked to hear that they send each other AUDIO letters. Audio letters? When they are so good at writing? When they have the chance to write to each other? Though, okay, why not? Henry James famously dictated his novels. Reines is amazingly articulate talking off the top of her head. Still, how is the pleasure the same? Williams does mention loving to actually write letters, so perhaps I shouldn’t judge.

Ariana Reines and Terry Tempest Williams, writers one would never expect to be buddies, but who bonded at Harvard Divinity School, are having a public Zoom discussion in order to sell books. It’s a lovely, friendly discussion, but I’m shocked, shocked to hear that they send each other AUDIO letters. Audio letters? When they are so good at writing? When they have the chance to write to each other? Though, okay, why not? Henry James famously dictated his novels. Reines is amazingly articulate talking off the top of her head. Still, how is the pleasure the same? Williams does mention loving to actually write letters, so perhaps I shouldn’t judge.

Well, I’ve looked at David Goodhart’s book (The Road to Somewhere – The New Tribes Shaping British Politics: 2017) and I’m obviously an Anywhere. [All quotes are from the Kindle edition]. “They tend to do well at school [Well, reasonably], then usually move from home to a residential university in their late teens [Yes] and on to a career in the professions [Teaching] that might take them to London or even abroad [Yes, indeed] for a year or two [or eighteen!]. Such people have portable ‘achieved’ identities, based on educational and career success which makes them generally comfortable and confident with new places and people [Generally!].”

Well, I’ve looked at David Goodhart’s book (The Road to Somewhere – The New Tribes Shaping British Politics: 2017) and I’m obviously an Anywhere. [All quotes are from the Kindle edition]. “They tend to do well at school [Well, reasonably], then usually move from home to a residential university in their late teens [Yes] and on to a career in the professions [Teaching] that might take them to London or even abroad [Yes, indeed] for a year or two [or eighteen!]. Such people have portable ‘achieved’ identities, based on educational and career success which makes them generally comfortable and confident with new places and people [Generally!].”