by Ashutosh Jogalekar

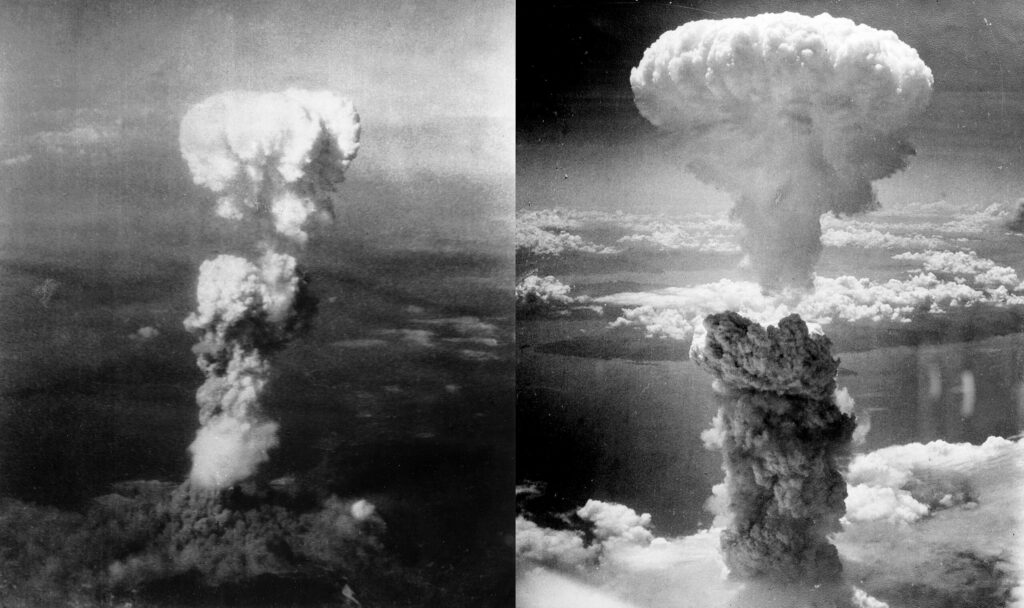

Eighty years ago on August 6, 1945, a blinding flash of light changed the world forever. The shadow of Hiroshima and Nagasaki has been with us ever since. Scientists struggled to make sense of the milennial force they had unleashed on the world. While science had always had some political implications, the advent of nuclear weapons took this relationship to a completely new level. For the first time humanity had definitively discovered the means of its destruction, and the work of scientists had made this jarring new reality possible. Scientists struggled with the new reality just like everyone else. Suddenly they were cast into the limelight as the new mandarins, becoming the politicians’ most important resource almost overnight. They were asked to offer advice on matters of seismic political and world significance for which they had not equipped themselves through their education and research.

Generally speaking, scientists who responded to this new reality fell into two camps. Let’s call them activists and stewards. Neither is meant to be a derogatory description. Neither group is “good” or “bad”, and both were important. To make the distinction clear, let’s consider some concrete examples. Robert Oppenheimer was an activist; Hans Bethe was a steward. Carl Sagan was an activist; Sidney Drell was a steward. Edward Teller was an activist; Herbert York was a steward. Leo Szilard was an activist; Enrico Fermi was a steward.

The primary difference between the two groups was that activists were revolutionary while stewards were evolutionary. Activists believed that the new age of nuclear weapons demanded urgent changes; stewards shared in the activists’ sense of urgency but believed that as painful as reality was, change needed to be worked from within, through institutional structures, through compromises and gradual advances.

The careers of Oppenheimer and Bethe provide a striking and instructive contrast between the two groups. Both were world-renowned physicists for their accomplishments in research and teaching and for establishing world-class centers of physics, Oppenheimer at the University of California, Berkeley and Bethe at Cornell University. Oppenheimer recognized Bethe as an outstanding theoretician and picked him to lead the important theoretical division of the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos. In turn Bethe enormously respected Oppenheimer’s intellect, astonishingly quick mind and vast knowledge of diverse fields. After the war both Bethe and Oppenheimer served as top consultants to the government on atomic energy and defense. While Bethe spearheaded the development of physics in the country from Cornell University, Oppenheimer served as director of the famed Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, where he worked with individuals like Einstein, Gödel and von Neumann. Both Bethe and Oppenheimer acted as wise men whom others consulted for advice on important matters of science and policy. Both men remained good friends till Oppenheimer’s death in 1967; Bethe was one of three speakers at Oppenheimer’s memorial service.

And yet both, because of their different backgrounds and temperaments, took a different approach to advising the government and trying to bring about change. Bethe was a steward and served as a consultant to the government on important matters throughout his long life. He played a key role in orchestrating the test ban under Kennedy that banned nuclear tests in the atmosphere, under water and in space. Oppenheimer was more of an activist who made powerful enemies who could not see his wisdom in warning about an arms race. He was a poet whose misfortune was to be cast in history as a politician. His eloquence and his provocative words, for instance his vivid assertion that the United States and the Soviet Union were like two “scorpions in a bottle” that would kill each other only at risk of mutual annihilation, did not endear himself with the generals and the politicians. This led to him being hauled in front of a tribunal which revoked his security clearance. Wounded and depressed by this ungrateful action, Oppenheimer continued to write, teach and speak on science and society but could not influence government policy.

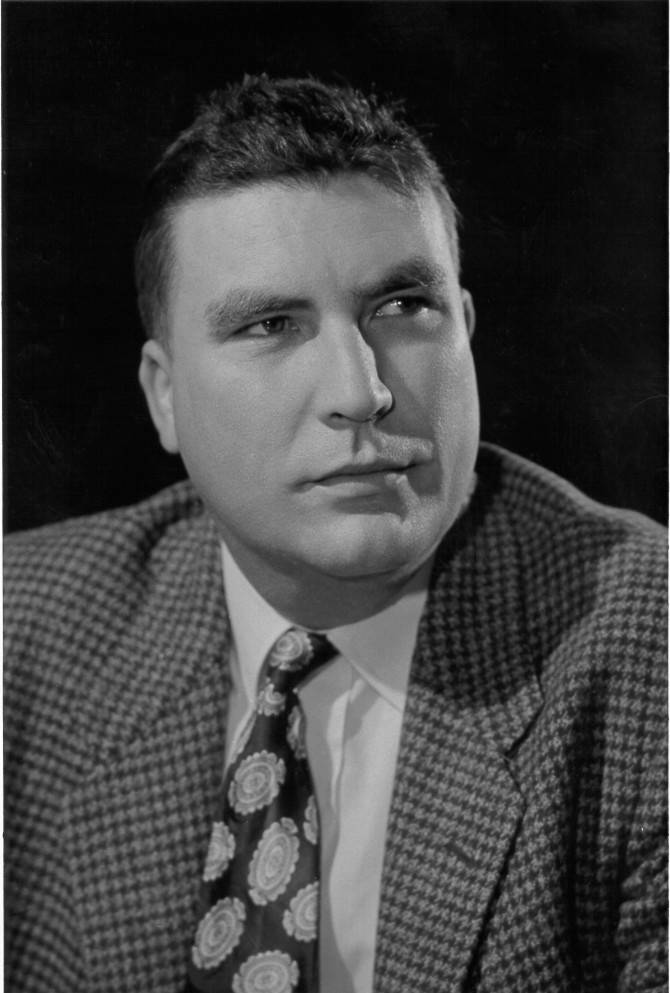

On the other hand, Bethe continued to be more valuable as a government advisor throughout his life – advising every president from Truman to Clinton – partly because he knew how to compromise and could be more diplomatic and modest. He could take courageous stands, but these stands often came in the form of well-argued and well-researched articles in magazines like Scientific American and the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. He was a key voice advising the government on a wide variety of problems, from test bans to missile defense, from nuclear power to nuclear fusion. When Bethe died in 2005 at the ripe old age of ninety-eight, he was recognized as one of the greatest physicists of the 20th century.

There were other activists and stewards who each left their mark on the fractious, complicated relationship between science and politics that had been set in motion by the invention of nuclear weapons. Edward Teller was an activist who wanted the United States to achieve supremacy over the Soviet Union in every way possible. He had trouble getting along with colleagues who thought that while he was brilliant, he failed to see ideas through and was obsessive and bitter. Teller vigorously pushed for a hydrogen bomb program even when it was far from certain that such a weapon would work and that it would have any strategic significance. Teller got his hydrogen bomb eventually, although it was the mathematician Stanislaw Ulam who catalyzed the key innovation. Bethe puckishly said that Teller was the mother of the hydrogen bomb because he conceived the idea and Ulam was the father because he provided the seed.

Frustrated by what he thought was the slow pace of thermonuclear development at the Los Alamos national laboratory, Teller agitated for a separate weapons lab. His efforts culminated in the founding of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory which has served as a valuable place for the invention of nuclear weapons. Livermore’s first director was Herbert York, a physicist who first spearheaded the agency which later became DARPA. But York was not an activist. He was a steward who believed that the United States’s existence depended on a robust but reasonable deterrence provided by nuclear weapons. York wrote a book titled “The Advisors: Oppenheimer, Teller and the Superbomb” which is a marvelous exposition of the decisions which resulted in the development of thermonuclear weapons. The best part of the book is the last part in which York lays out several different hypothetical scenarios that give credence to Oppenheimer’s view that that the United States not taking the initiative in building hydrogen bombs wouldn’t have made it fall behind the Soviet Union. In spite of being Teller’s protege, York deserves credit for objectively arguing Oppenheimer’s case and being a responsible steward.

Carl Sagan was another nuclear activist. In eloquent, clear prose that was informed by both science and the humanities, Sagan made a case for global cooperation and human prosperity. He decided early in his career that he would categorically not work on military research. One of his most important contributions was the idea, developed with other colleagues, of nuclear winter. Nuclear winter was a scenario in which even a “small scale” nuclear exchange of a few hundred kilotons, say between India and Pakistan, would lead to the injection of a large amount of dust and fallout products into the atmosphere that would block sunlight and lead to global cooling that would kill crops and lead to the deaths of millions of people. Sagan and his colleagues published their nuclear winter calculations in serious journals, but they were challenged by colleagues like Freeman Dyson who thought that the effects of nuclear winters were exaggerated. But the main purpose of nuclear winter was not to project accurate effects; it was to arouse righteous sentiment against nuclear weapons. And in this Sagan succeeded. Dyson conceded that while he did not necessarily agree with the nuclear winter calculations, he agreed with the elevation of public consciousness incited by the nuclear winter scenario.

Freeman Dyson who was a mentor and friend of mine was in fact a prime example of a steward. All his life he was part of the body of government advisors called JASON which advised the U.S. government on matters of defense and national security. But Dyson realized that lofty goals like the abolition of nuclear weapons do not contradict more modest goals like protection by nuclear submarines. In principle Dyson was an idealist, but in practice he was a realist. While agreeing that the abolition of nuclear weapons was a desirable goal, Dyson also realized that the road to that abolition involved the responsible stewardship of these weapons, and this goal in turn required the continued expertise of responsible experts who needed to work on these weapons. To this end, he advised the government on the Stockpile Stewardship program whose goal is to maintain the nuclear weapons of the United States without nuclear testing. In his book “Weapons and Hope”, Dyson lays out what I believe is the credo of the responsible steward, which is to work on defensive weapons and not work on offensive weapons.

As we approach continued challenges of nuclear deterrence and new emerging technologies and threats like AI and biotechnology, do we need more activists or stewards? The answer in my opinion is that we need a lot of stewards and a few activists, with an interchangeable mix of both. Stewards are necessary to keep things going. Activists are important in shaking things up. But these roles don’t have hard boundaries. Sometimes stewards need to be activists, like Hans Bethe was when he broke with the government on ballistic missile defense and Reagan’s Star Wars. Sometimes activists need to be stewards, like Robert Oppenheimer was when he advocated the use of tactical nuclear weapons on the battlefield and civil defense measures. Perhaps the one truth is that each age needs both activists and stewards, as long as each of them has the freedom to become the other.