by Mark Harvey

Don’t join the book burners. Don’t think you are going to conceal faults by concealing evidence that they ever existed. Don’t be afraid to go in your library and read every book… —President Dwight Eisenhower, 1953

The other day I stopped in at one of those coworking spaces to see if it would be worth joining in an effort to increase my productivity. Productivity, in my case, is a fancy word to describe getting my taxes done on time, answering a few emails, staying atop some small businesses, and doing a little writing. I’m not exactly a threat to mainland China.

Unfortunately the place I visited had all the charm of a gulag in far east Russia, with poor lighting, and about four pale characters staring at their computer screens as if they could see the eternal void in the universe and had a longing to visit. No thanks.

It did get me thinking about “third places,” and libraries in particular. I believe the term, third place, was coined by the writer Ray Oldenburg in his book The Great Good Place. First places are our homes, second places are where we work, and third places are where we go to get relief from the first and second places. They include churches, libraries, pubs, cafes, parks, gyms, and clubs.

My second place is a beautiful ranch in Colorado, so I have little to complain about, but when it comes to the close work of being on a computer, I really value third places. Scholars have described Oldenburg’s third place as having eight features including neutrality, leveling qualities, accommodation, a low profile, and a sense of home. In short, it’s a place that is welcoming, not fancy, free of social hierarchies, free of dues, and imparts no obligation to be there. That perfectly describes American libraries, one of our greatest institutions.

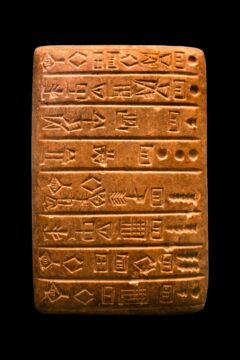

The earliest libraries in civilization were built more than five thousand years ago in Sumer, nowadays south-central Iraq. The “books” of that era were clay tablets that weighed upwards of 10 pounds per standard 8.5 x 11 sheet of paper. If you were a Sumerian and someone asked what you thought about The Epic of Gilgamesh, the best response might have been, “That’s some pretty dense reading.” Someone should check my math, but I figure that the clay-tablet equivalent of the information stored on an average modern flash drive would weigh close to 6,000 pounds.

Well before there was a nation, before We the People, there were public libraries in the American colonies. It’s hard to know which was the first public library in the United States, but there were certainly a handful of them in Boston and New York in the early 1700s.

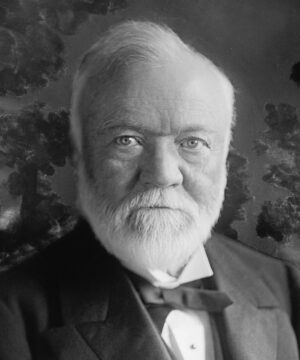

The great builder and benefactor of libraries in America was of course Andrew Carnegie, a poor Scottish immigrant who became a steel magnate. Carnegie was in many ways the quintessential American success story. He started out poor, educated himself, built a vastly successful business, and then did what many rich men and women never do: gave away a large part of his wealth toward helping society.

If reading about the vanity and avarice of some of our rich men in today’s world can curdle your heart, Carnegie’s trajectory could make your heart soar. His parents were poor weavers in Dunfermline, Scotland, and the entire family lived in a cottage with one room that served as bedroom, kitchen, and living room. After his family emigrated to the United States, Carnegie’s first job at age 13 was that of a “bobbin boy,” which meant changing spools of thread in a cotton mill. This was no summer internship but a job that meant working 12 hours per day for $1.20 per week.

Poor though he was, Carnegie came from a family that loved to read and he was a voracious reader himself. One of his uncles introduced him to poets such as Robert Burns and Robert Tannahill and he also read widely in historical texts such as George Bancroft’s voluminous History of the United States and Thomas Macaulay’s History of England.

In time, Carnegie built the biggest steel company in the world and amassed a huge fortune worth around $11 billion in today’s currency. Fantastically rich though he was, Carnegie thought the pursuit of money for the sake of money was the lowest form of idolatry and that rich men who didn’t give the bulk of their money away during their lifetime had failed.

Carnegie’s first American library opened in Braddock, Pennsylvania, in 1889. He built the library for his steelworkers with the belief that access to free books would further their aspirations as citizens. From there, he went on a massive worldwide building spree, constructing more than 2,500 libraries: 1,689 in the United States, 660 in the United Kingdom and Ireland, 125 in Canada, and various others in Australia, South Africa, New Zealand, Serbia, Belgium, France and Fiji.

Though designed in various styles ranging from Baroque to Beaux-Arts, most of the Carnegie funded libraries had a stairway entrance to represent the elevation of education, and a lamp on a pole to represent enlightenment.

If you include central, branch, and mobile units (bookmobiles), there are more than 17,000 libraries in the United States today. Those libraries circulate more than 600 million books and have around 1.5 billion in-person visits per year. To me, those statistics are about the most encouraging numbers we have in today’s screwed-up world. It means that for all the bigotry, violence, and conspiracy theorists, there are millions of Americans who trudge up the library steps in their town, pick out a book, or sit down to give a subject serious thought in that particularly American third space. It’s free and it’s wonderful!

The library I mostly use is in a small town and it’s of a quality far beyond what a small town deserves. It’s beautifully designed with lots of light, desks that face huge glass windows that look out on a small nature preserve, high-quality chairs, high-speed internet, lots of power outlets, special rooms for meetings, and a great staff. It even has a working fireplace. It’s like walking into the sort of library God would design if God had money (borrowed from George Bernard Shaw).

I’ve noticed there are lots of homeless people in many libraries I visit. On cold days, it has to be a great relief to be treated like a human being in a warm building if you’ve been living on the street. All across the nation, public libraries offer refuge to the poor and homeless. To their eternal credit, American libraries from coast to coast have worked to help the homeless regain a footing in the world. In Dallas, Texas, a town you might associate with the excesses of Nieman Marcus or oil barons, the city’s public library system has systematically worked to effectively help the poor and homeless. In 2013, The Dallas Public Library launched the Homeless Engagement Initiative. The program offers one-on-one assistance to patrons for things such as finding emergency shelters, housing information, writing resumes, and applying for jobs.

In a Stateline article, Sophie Quinton describes how the Dallas Library program helped Joe Borrego, a laid-off oil worker, get back on his feet. A pamphlet at the library helped him with the essentials of finding food, but it was the personal encouragement of staff there that eventually led to his finding new work and an apartment. Quinton quotes him saying, “Without that additional push, I’d probably still be sitting there on the homeless side of things.”

The work in Dallas is just one shining example of American libraries, coast to coast, facing the homeless issue—looking for solutions.

The most storied public library in the United States is The New York Public Library, which opened its doors in 1911 thanks to the bestowal of Samuel Tilman. Visitors to New York should not miss seeing the Rose Reading Room there, a vast expanse the length of a football field with fifty-feet-high ceilings. Many of our most celebrated authors have done their work in the Reading Room, including E.L. Doctorow, E.B. White, Norman Mailer, Tom Wolfe, Betty Friedan, and Robert Caro. With its Beaux-Arts architecture, immensity, and the lingering spirits of the great thinkers who worked there, the New York Public Library is quietly and quintessentially American.

On its 125th anniversary, The New York Public Library published a list of the ten most checked-out books of all time. On the list at number seven is Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury. The book has the distinction of being one of the most banned or challenged books in America as well. One of the great ironies of banning Fahrenheit 451 is that the heart of its story describes a dystopian America where books are banned and burned. Bradbury wrote the story in the early fifties, shortly after all the book burning in Nazi German and during the McCarthy era with its black-listing, repression, and paranoia.

It must have taken Bradbury considerable courage to write Fahrenheit 451 while McCarthy was trying to destroy the lives of so many other prominent American writers such as Dorothy Parker, Nelson Algren, and Arthur Miller. McCarthy encouraged librarians across the country to sort through their card catalogs and remove any material that could be construed as even remotely threatening. Some libraries removed hundreds of books.

Librarians across the country are facing another book-banning era today. According to the American Library Association, there were more attempts at censoring libraries in 2022 than in any year since they began keeping track. Groups such as Moms for Liberty are hell-bent on making sure that young readers never cross paths with any literature that doesn’t portray a sanitized version of homelife that never even existed. An aspiring novelist would have endless material satirizing this group of predominantly white women scouring our public and school libraries for anything straying from their idealized version of a pasteurized and sanitized America. They’re really just a gaggle of J. Edgar Hoovers in heels and hose.

Libraries are generally quiet places with quiet people focused on challenging passages in a good book, writing a story, studying to be an engineer, or just finding a warm harbor in a cold world. But from the smallest library in Ely, Nevada, to the soaring reading room in the New York Public Library, every day, millions of Americans do that most American thing: sit in one of our best third spaces to broaden themselves and improve their minds.

Ray Bradbury, who wrote one of the best sellers in American history and challenged the stinking overreach of McCarthy and his flunkies, couldn’t afford college.

He educated himself at the Los Angeles Public Library.