by Ashutosh Jogalekar

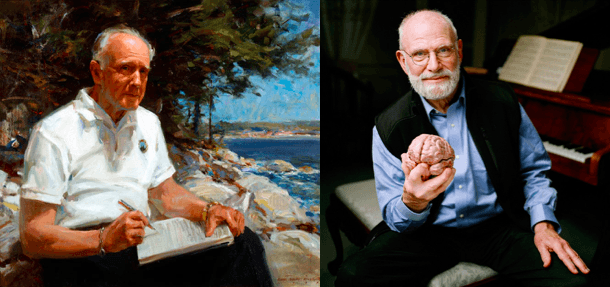

A rare and happy coincidence today: The birthdays of both John Archibald Wheeler and Oliver Sacks. Wheeler was one of the most prominent physicists of the twentieth century. Sacks was one of the most prominent medical writers of his time. Both of them were great explorers, the first of the universe beyond and the second of the universe within.

What made both men special, however, was that they transcended mere accomplishment in the traditional genres that they worked in, and in that process they stand as role models for an age that seems so fractured. Wheeler the physicist was also Wheeler the poet and Wheeler the philosopher. Throughout his life he transmitted startling new ideas through eloquent prose that was too radical for academic journals. Most of his important writings made their way to us through talks and books. Sacks the neurologist was far more than a neurologist, and Sacks the writer was much more than a writer. Both Wheeler and Sacks had a transcendent view of humanity and the universe, a view that is well worth taking to heart in our own self-centered times.

Their backgrounds shaped their views and their destiny. John Wheeler grew up in an age when physics was transforming our view of the universe. While he was too young to participate in the genesis of the twin revolutions of relativity and quantum mechanics, he came on stage at the right time to fully implement the revolution in the burgeoning fields of particle and nuclear physics.

After acquiring his PhD, Wheeler went on a fellowship to what was undoubtedly the mecca of physical thought – Niels Bohr’s Institute of Theoretical Physics in Copenhagen. By then Bohr had already become the grand old man of physics. While Einstein was retreating from the forefront of quantum mechanics, not believing that God would play such an inscrutable game of dice, Bohr and his pioneering disciples – Werner Heisenberg, Wolfgang Pauli and Paul Dirac, in particular – were taking the strange results of quantum mechanics at face value and interpreting them for the next generation. Particles that were waves, that superposed with themselves and that could be described only probabilistically, all found a place in Bohr’s agenda.

Bohr was famous for trying to describe physical reality as accurately as possible. This led to his maddening, Delphic utterances where he would go back and forth with a colleague to rework the fine points of his thinking, relentlessly questioning everyone’s reasoning including his own. But the process also illuminated both his passion to understand the world as well as his absolute insistence on precision and honesty. His talks and writings are often covered in a fine mist of interpretive haze, but once you ponder them enough they are wholly illuminating and novel. Bohr’s disciples did their best to spread his Copenhagen gospel throughout the world, and for the large part they succeeded spectacularly. When Wheeler joined Bohr in the mid 1930s, the grand old philosopher of physics was in the middle of his famous arguments with Einstein concerning the nature of reality. The so-called Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen paradox, published in back-to-back papers by Bohr, Einstein and their eponymous colleagues in 1935, was to set the stage for all quantum mechanical quarrels related to meaning and reality for the next half century.

For Wheeler, doing physics with Bohr was like playing ping-pong with an opponent possessing infinite patience. Back and forth the two went; arguing, refining, correcting, Wheeler doing most of the calculating and Bohr doing most of the talking. Wheeler came from the pragmatic American tradition of physics, later called the “shut up and calculate” tradition. While not particularly attuned back then to philosophical disputes, Wheeler rapidly absorbed Bohr’s avuncular, Socratic method of argument and teaching, later using it to create probably the finest school of theoretical physics in the United States during the postwar years. His opinion of Bohr stayed superlative till the end: “You can talk about people like Buddha, Jesus, Moses, Confucius, but the thing that convinced me that such people existed were the conversations with Bohr.”

In 1939, with Bohr as a sure guide, Wheeler made what was practically speaking probably the most important contribution of his career – an explanation of the mechanism of nuclear fission. The paper is a masterful application of both classical and quantum physics, treating the nucleus as an entity poised on the cusp between the quantum and the classical worlds. In the same issue of the Physical Review that published the Wheeler-Bohr paper, another paper appeared, a paper by Robert Oppenheimer and his student Hartland Snyder. In their paper, Oppenheimer and Snyder laid out the details of what we now call black holes. The seminal Oppenheimer-Snyder paper went practically unnoticed; the seminal Wheeler-Bohr paper spread like wildfire. The reason was simple. Both papers were published on the day Germany attacked Poland and started the Second World War. Just eight months before, German scientists had discovered a potentially awesome and explosive source of energy in the nuclear fission of uranium. The discovery and the Wheeler-Bohr paper made it clear to interested observers that weapons of immensely destructive power could now be made. The race was on. As a professor at Princeton University, Wheeler was in the thick of things.

He became an important part of the Manhattan Project, contributing crucial ideas especially to the design of the nuclear reactors that produced plutonium. He had a vested interest in seeing the bomb come to fruition as soon as possible: his brother, Joe, was fighting on the front in Europe. Joe did not know the details of the secret work John was doing, but the two words in his letter to John made his general understanding of Wheeler’s work clear – “Hurry up”, the letter said. Sadly, Joe was killed in Italy before the bomb could be fully developed. His inability to potentially save his brother’s life massively shaped Wheeler’s political views. From then on, while he did not quite embrace weapons of mass destruction with the same enthusiasm as his friend Edward Teller, his opinion was clear: if there was a bigger weapon, the United States should have it first. One of the hallmarks of Wheeler’s life and career was that in spite of his political leanings – his conservatism was in marked contrast to most of his colleagues’ liberal politics – he seems to have remained friends with everyone. Wheeler’s life is a good illustration, especially in these fraught times, of how someone can keep their politics from interfering with their fundamental decency and appreciation of decency in others.

His scientific gifts and political views led Wheeler to work on the hydrogen bomb amidst an environment of Communist hysteria, witch hunts and stripped security clearances. But after he had done his job perfecting thermonuclear weapons, Wheeler returned to his first love – pure physics. During the war, he had teamed up with an immensely promising young man with fire in his mind and a young wife dying in a hospital in Albuquerque. Richard Feynman and John Wheeler couldn’t have been different from each other; one the fast-talking, irreverent kid from New York City, the other a courtly, conservative, Southern-looking gentleman who wore pinstriped suits. And yet their essential honesty and drive to understand physics from the bottom up made them kindred souls. Feynman got his PhD under Wheeler and for the rest of his life loved and admired his mentor; his work with Wheeler also inspired Feynman’s own Nobel Prize winning work in quantum electrodynamics – the strange theory of the interaction between light and matter. Wheeler’s love for teaching and the art of argument he acquired from Bohr crystallized in his interactions with Feynman. It set the stage for the latter half of his life.

Wheeler is one of the very few scientists in history who did breakthrough work in two completely different branches of science. Before the war he had been an explorer of the infinitesimal, but now he made himself an intrepid Marco Polo of the infinitely large. In the 1950s Wheeler plunged headlong into the physics of gravitational collapse, starting out from where Oppenheimer and others had left off. Memorably, he became the man who christened Oppenheimer’s startling brainchildren: in a conference in New York, Wheeler called objects whose gravitational fields were so strong that they could not let even light escape ‘black holes’. Black holes and curved spacetime became the foci of Wheeler’s career. While pursuing this interest he contributed something even more significant: he essentially created the most important school of relativistic investigations in the United States. And combining this new love with his old love, he also created entire subfields of physics that are today engaging the best minds of our time – quantum gravity, quantum information and quantum computing, quantum entanglement and the philosophy of quantum theory.

As a teacher, Wheeler could give Niels Bohr a run for his mentorship. Not just content with supervising the usual flock of graduate students and postdocs, Wheeler took it upon himself to train promising undergraduates in the art of thinking about the physical world. Story after story flourishes of some young mind venturing with trepidation into Wheeler’s office for the first time, only to emerge dazed two or three hours later, staggering under the weight of papers and books and bursting with research ideas. In fact Wheeler supervised more senior research theses at Princeton than any other professor in the department’s history, and for the longest time he taught the freshman physics class: what better way to ignite a passion for physics than by taking a class as a freshman from one of the century’s most brilliant scientific minds? To top it all, he used to sometimes take his students to see a neighborhood resident at the famous address 112 Mercer Street – Albert Einstein. Sitting in Einstein’s room in a circle, the awestruck young minds would watch Wheeler trying to gently convince a perpetually resistant Einstein of the correctness of quantum ideas.

A very short list of students, postdocs and collaborators of Wheeler includes, along with Feynman: Jacob Bekenstein who forged startling links between black hole thermodynamics and relativity; Hugh Everett who came up with the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics, an interpretation which flew in the face of Niels Bohr’s Copenhagen Interpretation; Bryce Dewitt with whom Wheeler made important inroads into the deep realm of quantum gravity; and Kip Thorne, gravitational wave pioneer whose dogged efforts finally won him the Nobel Prize last year. With Thorne and Charles Misner Wheeler also wrote “Gravitation”, an authoritative doorstop of a book that has inspired and taught general relativity to generations of students. Very few teachers of theoretical physics equaled Wheeler in his influence and mentorship; certainly in the twentieth century, only Bohr, Arnold Sommerfeld and Max Born come to mind, and among American physicists, only Robert Oppenheimer and his school at Berkeley.

With his students Wheeler worked on some of the most preposterous extensions of nature’s theories that we can imagine: wormholes, quantum gravity, time travel, measurement in quantum theory. He constantly asked his pupils to think of crazy ideas, to extend our most hallowed theories to their breaking point, to think of the whole universe as a child’s playground. His colleagues often thought he was going crazy, but Feynman once corrected them: “Wheeler’s always been crazy”, he reminded everyone. Like his mentor Bohr, Wheeler became a master of the Delphic utterance, the deep philosophical speculation that could result in leaps and bounds in humanity’s understanding of the universe. Here’s one of those utterances: “Individual events. Events beyond law. Events so numerous and so uncoordinated that, flaunting their freedom from formula, they yet fabricate firm form”. The statement is vintage Wheeler; disarming in its ambiguity, deep in its implications, in equal parts physics, philosophy and poetry.

Many of Wheeler’s ideas were collected together in an essay collection titled “At Home in the Universe” which I strongly recommend. These essays showcase his wide-ranging interests and his gift for philosophy and uncommon prose and are full of paradoxes and puzzles. They also illustrate his warm friendship with many of the most famous names in physics including Bohr, Einstein, Fermi and Feynman. Along with “black hole”, he coined many other memorable phrases and statements: “It from Bit”, “Geometrodynamics”, “Mass without Mass”, and “Time is what prevents everything from happening at once”. He always believed that the universe is simpler than stranger, convinced that what is today’s strangeness and paradox will be tomorrow’s simple accepted wisdom.

John Wheeler died at the ripe old age of ninety-six, a legend among scientists. In affectionate tribute to his own way with words, a sixtieth birthday commemoration for him had called his work “Magic without Magic”, an that’s as good a way as any to remember this giant of science. A fitting epitaph? Many to choose from, but his sentiment about it being impossible to understand science without understanding people stands as a testament to his scientific brilliance and fundamental humanity: “No theory of physics that deals only with physics will ever explain physics. I believe that as we go on trying to understand the universe, we are at the same time trying to understand man.”

We come now to Oliver Sacks. Strangely enough, it took me some time to warm up to Sacks’s writing. I read about the man who mistook his wife for a hat, of course, and the patients with anosmia and colorblindness and the famous patients of ‘Awakenings’ who had been trapped in their bodies and then miraculously – albeit temporarily – resurrected. But I always found Sacks’s descriptions a bit too detached and clinical. It was when I read the charming “Uncle Tungsten” that I came to appreciate the man’s wide-ranging interests. But it was his autobiography “On the Move” that really drove home the unquenchable curiosity, intense desire for connecting to life and human beings and sheer love for living in all its guises that permeated Sacks’s being. I was so moved and satiated by the book that I read it again right after reading the last page, and read it a third time a few days later. After this I went back to almost the entirety of Sacks’s oeuvre and enjoyed it. So mea culpa, Dr. Sacks, and thanks for the reeducation.

Like Wheeler Sacks was born to educated parents in London, both of whom were doctors. He clearly acquired his interest in patients, both as medical curiosities and as human beings from his parents. A voracious reader, he had many interests while growing up – Darwin and chemistry were two which he retained throughout his life – and like other Renaissance men found it hard to settle on one. But family background and natural inclination led him to study medicine at Oxford and, finding England too provincial, he shipped to the New World, first to San Francisco and then to New York.

Throughout his life, Sacks’s most distinguishing quality was the sheer passion with which he clung to various activities. These ranged from the admirable to the foolhardy. For instance, Sacks didn’t just “do bodybuilding”, he became obsessed with it to the point of winning a California state championship and risking permanent damage in his muscles. He didn’t just “ride motorcycles”, he would take his charger on eight hundred mile rides to Utah and Arizona over a single weekend. He didn’t just “do drugs”, he flooded his body with amphetamines to the point of almost killing himself. And he didn’t just “practice medicine” or writing, he turned them into an observational art form without precedent. It is this intense desire for a remarkable diversity of people and things that defined Oliver Sacks’s life. And yet Sacks was lonely; as a gay man who repressed his sexuality after a devastating reception from his mother and a series of failed encounters during his bodybuilding days, he refrained from romantic relationships for four decades before finally finding love in his seventies. It was perhaps his own struggle with his identity, combined with recurring maladies like depression and migraines, that made Sacks sympathize so deeply with his patients.

Two things made Sacks wholly unique as a neurological explorer. The writer Andrew Solomon once frankly remarked in a review of one of Sacks’s books that as purely a writer or purely a neurologist, while Sacks was very good, he probably wasn’t in the first rank. But nobody else could straddle the two realms with as much ease, warmth and informed narrative as he could. It was the intersection that made him one of a kind. That and his absolutely transparent, artless style, amply demonstrated in “On the Move”. He was always the first one to admit to follies, mistakes and missed opportunities.

For Sacks his patients were patients second and human beings first. He was one of the first believers in what is today called “neurodiversity”, long before the idea became fashionable. Neurodiversity means the realization that even people with rather extreme neurological conditions show manifestations of characteristics that are present in “normal” human beings. Even when Sacks told us about the most bizarre kind of patients, he saw them as lying on a continuum of human abilities and powers. He saw the basic humanity among patients frozen in space and time when the rest of the world simply saw them as “cases”. And he displayed all this warmth and understanding toward his patients without ever wallowing in the kind of sweet sentimentality that can mark so much medical writing trying to be literature.

Sacks persisted in exploring an astonishing landscape of aspects of the human mind until his last days. Whether it was music or art, mathematics or natural history, he always had something interesting to say. The one exception – and this was certainly a refreshing part of his writing – was politics; as far as I can tell, Sacks was almost wholly apolitical, preferring to focus on the constants of nature and the human mind than the ephemeral foibles of mankind. His columns in the New York Times were always a pleasure, and in his last few – written after he had announced his impending death in a moving piece – he explored topics dear to his heart; Darwin, the periodic table, his intense love of music, his satisfying and strange connection to Judaism as an atheist, and his gratitude for science, friends and the opportunity to be born, thrive and learn in a world full of chaos. In the column announcing the inevitable end he said, “I cannot pretend I am without fear. But my predominant feeling is one of gratitude. I have loved and been loved”.

Why remember John Wheeler and Oliver Sacks today? Because one taught us to look at the universe beyond ourselves, and the other taught us to look within ourselves. Both appealed to the better angels of our nature and to what we have in common rather than what separates us, asking us to constantly stay curious. These lessons seem to be quite relevant to our day and age. Wheeler told us that the laws of physics and the deep mysteries of the universe, even if they may not care about our fragile, bickering world of politics and social strife, beckon each one of us to explore their limits and essence irrespective of our race, nationality or gender. Sacks appealed to our common humanity and told us that deep within the human brain runs a thread that connects all of us on a continuum, independent again of our race, gender, nationality and political preferences. Two messages should stay with us:

Sacks: “Above all, I have been a sentient being, a thinking animal, on this beautiful planet, and that in itself has been an enormous privilege and adventure.”

Wheeler: “Behind it all is surely an idea so simple, so beautiful, that when we grasp it – in a decade, a century, or a millennium – we will all say to each other, how could it have been otherwise? How could we have been so stupid?”