by Thomas O’Dwyer

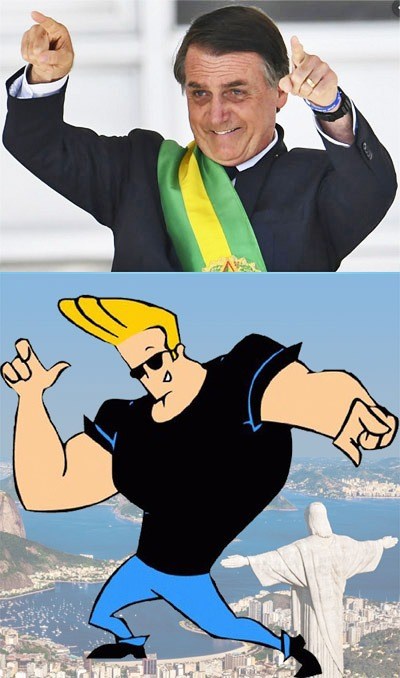

Brazil’s president Jair Bolsonaro fired the head of the agency which monitors Amazon deforestation. “Fired” is an unfortunate word here – flames sweep across the country and down into Bolivia. Scientists and environmentalists have been alarmed by how quickly their predictions, that Bolsonaro’s aggressive anti-conservation agenda would boost deforestation, have come to pass. Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research (Inpe), publishes monthly deforestation alerts and has reported around 80,000 wildfires in Brazil since January, 40,000 of them in the Amazon rain-forest.

Bolsonaro was incensed as first the local, and then international media started picking up what are publicly-available statistics. “Most of the foreign press has a completely distorted image of who I am and what I intend to do here with our policies and for the future of our Brazil,” he said. “I perfectly understand the level of the poisoning that is done to Brazil by the foreign press.” He declared that the data from the Inpe space research institute was a pack of lies and set off down the well-trodden right-wing Conspiracy Road. Read more »