Olga Khazan in The Atlantic:

I’ve timed calls from PR people to coincide with my commute home, since that’s the only “free” time I had to talk. On a recent cross-country trip to see my parents, I spent a day doing my work expenses. Constant pressure in my profession has made me go to great lengths to minimize how much labor I perform outside of work. I once made my boyfriend pay me for the hours I spent booking flights and hotels for our vacation.

The reasons behind this “madness,” as Schulte put it, are familiar, and they’re not specific to journalism. American workers—especially those in white-collar professions—are working longer hours. Women are often the default chore-doers and child-tenders, even in relationships that strive for egalitarianism. The solution from career gurus has historically been to try to squeeze both work and life into the overpacked Tupperware that is your day. Check emails during the kids’ swim meet, they say, or pick up a hobby to “take your mind off work”—and take up even more time you don’t have.

Busy workers have been trying and failing at these types of hacks for decades. This fruitless cycle suggests that work-life balance is not independently achievable for most overworked people, if not outright impossible.

More here.

What a difference a decade makes. In 1940 George Orwell published his eighth book, the essay collection Inside the Whale, but when the Nazis in the same year drew up a list of Britons to be arrested after the planned invasion, his name wasn’t included. It was, observes Dorian Lynskey in his superb new book, ‘a kind of snub’. By the time Orwell died in January 1950, however, he was being acclaimed around the Western world as one of the great defenders of democracy and liberty, and had just been adjudged, for the first time, worthy of an entry in Who’s Who.

What a difference a decade makes. In 1940 George Orwell published his eighth book, the essay collection Inside the Whale, but when the Nazis in the same year drew up a list of Britons to be arrested after the planned invasion, his name wasn’t included. It was, observes Dorian Lynskey in his superb new book, ‘a kind of snub’. By the time Orwell died in January 1950, however, he was being acclaimed around the Western world as one of the great defenders of democracy and liberty, and had just been adjudged, for the first time, worthy of an entry in Who’s Who. A

A Forty years ago, Nathaniel Rich tells us in Losing Earth, global warming was better understood by the general public and US politicians than at any time since. Moreover, the opportunity to broker a global treaty to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases had presented itself, and the political will existed for the US to lead on the issue. Had action been taken, we could have stopped climate change in its tracks, much as we halted ozone depletion with the 1989 Montreal Protocol to phase out chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs).

Forty years ago, Nathaniel Rich tells us in Losing Earth, global warming was better understood by the general public and US politicians than at any time since. Moreover, the opportunity to broker a global treaty to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases had presented itself, and the political will existed for the US to lead on the issue. Had action been taken, we could have stopped climate change in its tracks, much as we halted ozone depletion with the 1989 Montreal Protocol to phase out chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs). As Speaker of the House

As Speaker of the House  You know a book has entered your bloodstream when the ground beneath your feet, once viewed as bedrock, suddenly becomes a roof to unknown worlds below. The British writer

You know a book has entered your bloodstream when the ground beneath your feet, once viewed as bedrock, suddenly becomes a roof to unknown worlds below. The British writer  Today we’re going to discuss the Canterbury Tales. You’ve just written a biography of Geoffrey Chaucer. What would someone learn from your biography about Chaucer that they might not have known before?

Today we’re going to discuss the Canterbury Tales. You’ve just written a biography of Geoffrey Chaucer. What would someone learn from your biography about Chaucer that they might not have known before? “Culture is the secret of humanity’s success” sounds like the most vapid possible thesis.

“Culture is the secret of humanity’s success” sounds like the most vapid possible thesis.  They called it the épuration sauvage, the wild purge, because it was spontaneous and unofficial. But, yes, it was savage, too. In the weeks and months following the

They called it the épuration sauvage, the wild purge, because it was spontaneous and unofficial. But, yes, it was savage, too. In the weeks and months following the  Mendelssohn’s Wiki page says his grave has been reconstructed. Not surprising: grand historical narratives are everywhere legible in Berlin’s built environment. The Jewish cemetery where he’s buried became part of East Berlin after the war, falling into even further disrepair after the Nazi years. His grave, as well as many others, was only reconstructed in the 2000s.

Mendelssohn’s Wiki page says his grave has been reconstructed. Not surprising: grand historical narratives are everywhere legible in Berlin’s built environment. The Jewish cemetery where he’s buried became part of East Berlin after the war, falling into even further disrepair after the Nazi years. His grave, as well as many others, was only reconstructed in the 2000s. In a 2017 essay for the magazine Fare, Ayşegül Savaş described a game she played as a high school student in Istanbul. She and a friend strapped on backpacks and pretended to be foreigners in Istanbul’s tourist quarter. The purpose of “the tourist game,” Savaş remembered, “was to talk to people in English of varying accents, throwing in a handful of mispronounced Turkish words.” They asked locals for directions to Istanbul landmarks, had their pictures taken in front of palaces and felt “overjoyed when our identities were not revealed, all the more if anyone showed an interest in us and asked where we were from.” The game, Savaş explained, “made us feel like we were in control while giving us the freedom to explore as we pleased; our city took on new wonder when viewed from the imaginary foreign gaze.”

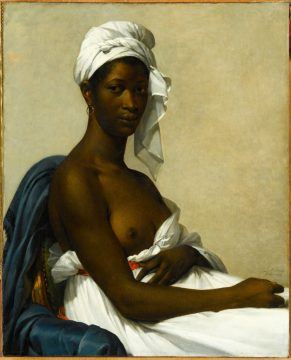

In a 2017 essay for the magazine Fare, Ayşegül Savaş described a game she played as a high school student in Istanbul. She and a friend strapped on backpacks and pretended to be foreigners in Istanbul’s tourist quarter. The purpose of “the tourist game,” Savaş remembered, “was to talk to people in English of varying accents, throwing in a handful of mispronounced Turkish words.” They asked locals for directions to Istanbul landmarks, had their pictures taken in front of palaces and felt “overjoyed when our identities were not revealed, all the more if anyone showed an interest in us and asked where we were from.” The game, Savaş explained, “made us feel like we were in control while giving us the freedom to explore as we pleased; our city took on new wonder when viewed from the imaginary foreign gaze.” For a long time, and even very recently, artworks with black models—or by black artists—were collected sparingly by museums, in part because they weren’t considered to fit into any standard art-historical narratives. Between 2008 and 2018, for instance, only 2.4 percent of purchases and donations in thirty of the best-known American museums were works by African American artists, according to an analysis by In Other Words and ARTNews. Only 7.6 percent of exhibitions concerned African American artists. From Modernism through postwar Abstract Expressionism, work by black painters still represented a catch-22: they were either too much about the black experience and thus didn’t seem to fit into the European timeline of art history, or they were too reliant on the abstract when the few museums that did collect black artists wanted figurative works that represented “the black experience.” “It’s pretty hard to explain by any other means than to say there was an actual, pretty systemic overlooking of this kind of work,” said Ann Temkin, the curator of painting and sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, in a recent

For a long time, and even very recently, artworks with black models—or by black artists—were collected sparingly by museums, in part because they weren’t considered to fit into any standard art-historical narratives. Between 2008 and 2018, for instance, only 2.4 percent of purchases and donations in thirty of the best-known American museums were works by African American artists, according to an analysis by In Other Words and ARTNews. Only 7.6 percent of exhibitions concerned African American artists. From Modernism through postwar Abstract Expressionism, work by black painters still represented a catch-22: they were either too much about the black experience and thus didn’t seem to fit into the European timeline of art history, or they were too reliant on the abstract when the few museums that did collect black artists wanted figurative works that represented “the black experience.” “It’s pretty hard to explain by any other means than to say there was an actual, pretty systemic overlooking of this kind of work,” said Ann Temkin, the curator of painting and sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, in a recent  If scientists want to simulate a brain that can match human intelligence, let alone eclipse it, they may have to start with better building blocks—computer chips inspired by our brains. So-called neuromorphic chips replicate the architecture of the brain—that is, they talk to each other using “neuronal spikes” akin to a neuron’s action potential. This spiking behavior allows the chips to consume very little power and remain power-efficient even when tiled together into very large-scale systems. “The biggest advantage in my mind is scalability,” says

If scientists want to simulate a brain that can match human intelligence, let alone eclipse it, they may have to start with better building blocks—computer chips inspired by our brains. So-called neuromorphic chips replicate the architecture of the brain—that is, they talk to each other using “neuronal spikes” akin to a neuron’s action potential. This spiking behavior allows the chips to consume very little power and remain power-efficient even when tiled together into very large-scale systems. “The biggest advantage in my mind is scalability,” says

The question of what kinds of physical systems are conscious “is one of the deepest,

The question of what kinds of physical systems are conscious “is one of the deepest,  Granted, the U.S. was by this point pretty much dead to me, as I had determined from periodic visits that it was in the interest of my sanity to avoid the country altogether. Frida Kahlo once observed: “I find that Americans completely lack sensibility and good taste. They are boring, and they all have faces like unbaked rolls.”And yet this, perhaps, is the least of the problems.

Granted, the U.S. was by this point pretty much dead to me, as I had determined from periodic visits that it was in the interest of my sanity to avoid the country altogether. Frida Kahlo once observed: “I find that Americans completely lack sensibility and good taste. They are boring, and they all have faces like unbaked rolls.”And yet this, perhaps, is the least of the problems.