Alex Shashkevich in Phys.Org:

In a new study, Stanford psychologists examined why some people respond differently to an upsetting situation and learned that people’s motivations play an important role in how they react. Their study found that when a person wanted to stay calm, they remained relatively unfazed by angry people, but if they wanted to feel angry, then they were highly influenced by angry people. The researchers also discovered that people who wanted to feel angry also got more emotional when they learned that other people were just as upset as they were, according to the results from a series of laboratory experiments the researchers conducted.

In a new study, Stanford psychologists examined why some people respond differently to an upsetting situation and learned that people’s motivations play an important role in how they react. Their study found that when a person wanted to stay calm, they remained relatively unfazed by angry people, but if they wanted to feel angry, then they were highly influenced by angry people. The researchers also discovered that people who wanted to feel angry also got more emotional when they learned that other people were just as upset as they were, according to the results from a series of laboratory experiments the researchers conducted.

…To learn how people react to upsetting situations and respond to others around them, the researchers examined people’s anger toward politically charged events in a series of laboratory studies with 107 participants. The team also analyzed almost 19 million tweets in response to the police shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014. In the laboratory studies, the researchers showed participants images that could trigger upsetting emotions, for example, people burning the American flag and American soldiers abusing prisoners in Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. The researchers also told participants how other people felt about these images. The researchers found that participants who wanted to feel less angry were three times more likely to be more influenced by people expressing calm emotions than by angry people. But participants who wanted to feel angry were also three times more likely to be influenced by other people angrier than them, as opposed to people with calmer emotions. The researchers also found that these participants got more emotional when they learned that others also felt similar emotions to them.

More here.

Let’s go around the room and introduce ourselves.

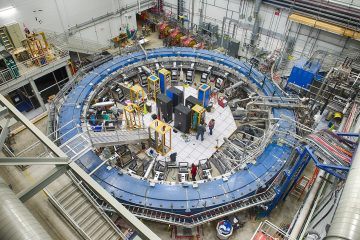

Let’s go around the room and introduce ourselves. Physicists count 25 elementary particles that, for all we presently know, cannot be divided any further. They collect these particles and their interactions in what is called the Standard Model of particle physics.

Physicists count 25 elementary particles that, for all we presently know, cannot be divided any further. They collect these particles and their interactions in what is called the Standard Model of particle physics. In the spring of 1938, the Mexican press reported on the perils faced by Sigmund Freud in post-Anschluss Austria: The Gestapo had raided the offices of the Psychoanalytic Publishing House, searched the apartment at Berggasse 19, and briefly detained his daughter Anna. Freud himself — once reluctant to consider emigration — made up his mind to leave Vienna, but his decision seemed to come too late: obtaining an exit visa had become a nearly impossible ordeal for Austrian Jews. Freud would have been trapped in Vienna had it not been for a group of powerful friends who launched a full-scale diplomatic campaign on his behalf: William Bullitt, the American ambassador to France; Ernest Jones, who lobbied British Members of Parliament; and Princess Marie Bonaparte, who was in direct communication with President Roosevelt himself.

In the spring of 1938, the Mexican press reported on the perils faced by Sigmund Freud in post-Anschluss Austria: The Gestapo had raided the offices of the Psychoanalytic Publishing House, searched the apartment at Berggasse 19, and briefly detained his daughter Anna. Freud himself — once reluctant to consider emigration — made up his mind to leave Vienna, but his decision seemed to come too late: obtaining an exit visa had become a nearly impossible ordeal for Austrian Jews. Freud would have been trapped in Vienna had it not been for a group of powerful friends who launched a full-scale diplomatic campaign on his behalf: William Bullitt, the American ambassador to France; Ernest Jones, who lobbied British Members of Parliament; and Princess Marie Bonaparte, who was in direct communication with President Roosevelt himself. The discarded ending of Camera Obscura, transcribed and translated here for the first time, sheds light on

The discarded ending of Camera Obscura, transcribed and translated here for the first time, sheds light on  Sylvia Plath was hungry for new experiences when she returned to Smith College as a junior in the fall of 1952 and wrote “Mary Ventura and the Ninth Kingdom.” Over the summer she won a $500 prize in the Mademoiselle fiction writing contest with her short story “Sunday at the Mintons’.” When this psychological story was later featured in the Fall 1952 issue of the Smith Review, a literary journal Plath helped revive, it earned her the respect of Mary Ellen Chase, a successful author of novels, critical writings, and commentaries on Biblical literature who became Plath’s trusted mentor. In recommending Plath for graduate school, Chase wrote that in her twenty-seven years as an English professor at Smith she had not known a more gifted “literary artist.” Professor Chase contributed the first article to the Fall 1952 issue of the Smith Review—a definition of Smith College: “the one thing we are afraid of is apathy and indifference toward learning and toward life.” In “Mary Ventura and the Ninth Kingdom,” Plath reinforces Chase’s criticism of complacency when Mary’s traveling companion remarks sadly that others on the train “are so blasé, so apathetic that they don’t even care about where they are going.

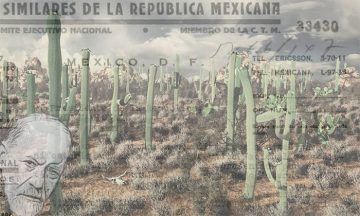

Sylvia Plath was hungry for new experiences when she returned to Smith College as a junior in the fall of 1952 and wrote “Mary Ventura and the Ninth Kingdom.” Over the summer she won a $500 prize in the Mademoiselle fiction writing contest with her short story “Sunday at the Mintons’.” When this psychological story was later featured in the Fall 1952 issue of the Smith Review, a literary journal Plath helped revive, it earned her the respect of Mary Ellen Chase, a successful author of novels, critical writings, and commentaries on Biblical literature who became Plath’s trusted mentor. In recommending Plath for graduate school, Chase wrote that in her twenty-seven years as an English professor at Smith she had not known a more gifted “literary artist.” Professor Chase contributed the first article to the Fall 1952 issue of the Smith Review—a definition of Smith College: “the one thing we are afraid of is apathy and indifference toward learning and toward life.” In “Mary Ventura and the Ninth Kingdom,” Plath reinforces Chase’s criticism of complacency when Mary’s traveling companion remarks sadly that others on the train “are so blasé, so apathetic that they don’t even care about where they are going. Although Chávez—born on this date in 1899—received his earliest musical training from his brother, and though he did study for a time with the composer Manuel Ponce, he largely taught himself how to write music by studying the scores of others. Early on, he became interested in furthering the cause of Mexican classical music, while reimagining its possibilities in the 20th century. Should it draw heavily from folk styles? How Mexican should it be? How avant-garde? Perhaps most crucial of all: How could a composer forge a style out of so many various elements: native Indian music, the plainsong brought by the conquistadores, the peasant dances of the countryside, the ballad-like corridos—to say nothing of the European symphonic and operatic literature? These questions must have been swimming in his head when, at the age of 21, Chávez traveled to Austria, Germany, and France. In Paris, he befriended Paul Dukas (composer of The Sorcerer’s Apprentice), who instructed the young man to incorporate vernacular Mexican music into his pieces, pointing to the example of Manuel de Falla, who had been doing similar things in Spain with Spanish music.

Although Chávez—born on this date in 1899—received his earliest musical training from his brother, and though he did study for a time with the composer Manuel Ponce, he largely taught himself how to write music by studying the scores of others. Early on, he became interested in furthering the cause of Mexican classical music, while reimagining its possibilities in the 20th century. Should it draw heavily from folk styles? How Mexican should it be? How avant-garde? Perhaps most crucial of all: How could a composer forge a style out of so many various elements: native Indian music, the plainsong brought by the conquistadores, the peasant dances of the countryside, the ballad-like corridos—to say nothing of the European symphonic and operatic literature? These questions must have been swimming in his head when, at the age of 21, Chávez traveled to Austria, Germany, and France. In Paris, he befriended Paul Dukas (composer of The Sorcerer’s Apprentice), who instructed the young man to incorporate vernacular Mexican music into his pieces, pointing to the example of Manuel de Falla, who had been doing similar things in Spain with Spanish music. Thirty years ago socialism was dead and buried. This was not an illusion or a temporary hiccup, a point all the more important to emphasize up front in light of its recent revival in this country and around the world. There was no reason this resurrection had to happen; no law of nature or history compelled it. To understand why it did is to unlock a door, behind which lies something like the truth of our age.

Thirty years ago socialism was dead and buried. This was not an illusion or a temporary hiccup, a point all the more important to emphasize up front in light of its recent revival in this country and around the world. There was no reason this resurrection had to happen; no law of nature or history compelled it. To understand why it did is to unlock a door, behind which lies something like the truth of our age. Entering Red Bull Arts Detroit, housed in the cavernous basement of the old Eckhardt & Becker Brewery in Eastern Market, you’re lured toward the main exhibition space by a pink fluorescent glow. The curious light emanates from a neon sign by the multidisciplinary Detroit artist Tiff Massey, one of Red Bull’s three artists in residence for the program’s first cycle of 2019, reading, “Bitch don’t touch MY HAIR!!” Written in cursive font and followed by exactly two exclamation points, it’s both foreboding and inviting, an entryway into Massey’s world. Massey, who holds an MFA in metalsmithing from Cranbrook Academy of Art, has exhibited in international galleries across Europe, but she’s adamant about who she creates for: black women. The centerpiece of her Red Bull Arts Detroit exhibition is a shrine-like display of 22 hairstyles, each braided and beaded in the same splendid shade of gold, and walled in on either side by distorted black-and-white photographs from an African-American hair salon, which feature primarily caucasian models. On an adjacent wall is a row of oversized pink barrettes repurposing another aspect of Detroit’s history: big manufacturing. “Craftsmanship is first,” Massey tells curator Laura Raicovich in the following conversation. “I want you to be seduced by the work. Whether it’s the colors, or the form, or whatever.”

Entering Red Bull Arts Detroit, housed in the cavernous basement of the old Eckhardt & Becker Brewery in Eastern Market, you’re lured toward the main exhibition space by a pink fluorescent glow. The curious light emanates from a neon sign by the multidisciplinary Detroit artist Tiff Massey, one of Red Bull’s three artists in residence for the program’s first cycle of 2019, reading, “Bitch don’t touch MY HAIR!!” Written in cursive font and followed by exactly two exclamation points, it’s both foreboding and inviting, an entryway into Massey’s world. Massey, who holds an MFA in metalsmithing from Cranbrook Academy of Art, has exhibited in international galleries across Europe, but she’s adamant about who she creates for: black women. The centerpiece of her Red Bull Arts Detroit exhibition is a shrine-like display of 22 hairstyles, each braided and beaded in the same splendid shade of gold, and walled in on either side by distorted black-and-white photographs from an African-American hair salon, which feature primarily caucasian models. On an adjacent wall is a row of oversized pink barrettes repurposing another aspect of Detroit’s history: big manufacturing. “Craftsmanship is first,” Massey tells curator Laura Raicovich in the following conversation. “I want you to be seduced by the work. Whether it’s the colors, or the form, or whatever.”

Nine months can make a person, or remake her. In October, 1997,

Nine months can make a person, or remake her. In October, 1997,  Why organisms began having sex, rather than simply reproducing asexually as life did for billions of years—and still does, in the case of single-celled organisms and some plants and fungi—is a bit of a mystery. Sexual reproduction evolved around a billion years ago or more, despite the additional energy required and the seeming hinderance of needing to find a suitable mate. Prevailing theories hold that sex became the dominant form of reproduction due to the benefits of greater genetic diversity, allowing offspring to adapt to changing environments and keeping species one step ahead of parasites that evolved to plague the parents.

Why organisms began having sex, rather than simply reproducing asexually as life did for billions of years—and still does, in the case of single-celled organisms and some plants and fungi—is a bit of a mystery. Sexual reproduction evolved around a billion years ago or more, despite the additional energy required and the seeming hinderance of needing to find a suitable mate. Prevailing theories hold that sex became the dominant form of reproduction due to the benefits of greater genetic diversity, allowing offspring to adapt to changing environments and keeping species one step ahead of parasites that evolved to plague the parents.

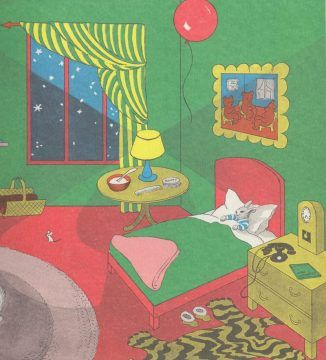

Something unsettling resides at the heart of the most beloved books for very young children—that is, the literature for illiterates. This note is a belated attempt to grapple with the horror of infinite regression as it manifests in certain of these works, and perhaps to sound the alarm for parent-caretaker voice-over providers who are too sleep-deprived to notice what’s actually going on.

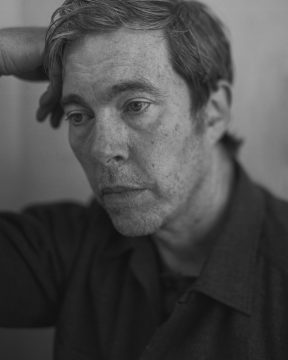

Something unsettling resides at the heart of the most beloved books for very young children—that is, the literature for illiterates. This note is a belated attempt to grapple with the horror of infinite regression as it manifests in certain of these works, and perhaps to sound the alarm for parent-caretaker voice-over providers who are too sleep-deprived to notice what’s actually going on. In 1990, using the name Smog, the singer and songwriter Bill Callahan released his début album, “Sewn to the Sky.” It’s a discordant, inscrutable, and periodically frustrating collection of mostly instrumental, low-fidelity noise, and contains few hints of the lucid and tender folk music that he would be making almost thirty years later. In 1991, Callahan signed with Drag City, a Chicago-based independent record label that specializes in oddball rock and roll. He began collaborating with the producers Jim O’Rourke, who was later a member of

In 1990, using the name Smog, the singer and songwriter Bill Callahan released his début album, “Sewn to the Sky.” It’s a discordant, inscrutable, and periodically frustrating collection of mostly instrumental, low-fidelity noise, and contains few hints of the lucid and tender folk music that he would be making almost thirty years later. In 1991, Callahan signed with Drag City, a Chicago-based independent record label that specializes in oddball rock and roll. He began collaborating with the producers Jim O’Rourke, who was later a member of  There is no concise answer to the question ‘what is Bauhaus?’ First it was a school with a specific curriculum in art and design. Later, it became a style and a movement and a look (geometric, elegant, spare, modern) that could be found to greater and lesser degrees in art, craft and architecture all over the world. But in retrospect, I think it is fair to say that Bauhaus was always an attempt to fuse the craft and aesthetic ideas of a pre-modern age with the realities of 20th century industry and technology. Bauhaus wanted to find out how materials like concrete and steel and glass could be beautiful and could be shaped and designed in such a way as to serve the aesthetic needs of humankind. In this, Bauhaus was very much in the spirit of the movements that preceded it, like Arts and Crafts and Art Nouveau. But Bauhaus went further than any of those movements in its embrace of what we now think of as the Modern with a big ‘M’. Some would say it went too far.

There is no concise answer to the question ‘what is Bauhaus?’ First it was a school with a specific curriculum in art and design. Later, it became a style and a movement and a look (geometric, elegant, spare, modern) that could be found to greater and lesser degrees in art, craft and architecture all over the world. But in retrospect, I think it is fair to say that Bauhaus was always an attempt to fuse the craft and aesthetic ideas of a pre-modern age with the realities of 20th century industry and technology. Bauhaus wanted to find out how materials like concrete and steel and glass could be beautiful and could be shaped and designed in such a way as to serve the aesthetic needs of humankind. In this, Bauhaus was very much in the spirit of the movements that preceded it, like Arts and Crafts and Art Nouveau. But Bauhaus went further than any of those movements in its embrace of what we now think of as the Modern with a big ‘M’. Some would say it went too far.