Ryan Whitwam at Ars Technica:

Google wasn’t around for the advent of the World Wide Web, but it successfully remade the web on its own terms. Today, any website that wants to be findable has to play by Google’s rules, and after years of search dominance, the company has lost a major antitrust case that could reshape both it and the web.

Google wasn’t around for the advent of the World Wide Web, but it successfully remade the web on its own terms. Today, any website that wants to be findable has to play by Google’s rules, and after years of search dominance, the company has lost a major antitrust case that could reshape both it and the web.

The closing arguments in the case just wrapped up last week, and Google could be facing serious consequences when the ruling comes down in August. Losing Chrome would certainly change things for Google, but the Department of Justice is pursuing other remedies that could have even more lasting impacts. During his testimony, Google CEO Sundar Pichai seemed genuinely alarmed at the prospect of being forced to license Google’s search index and algorithm, the so-called data remedies in the case. He claimed this would be no better than a spinoff of Google Search. The company’s statements have sometimes derisively referred to this process as “white labeling” Google Search.

But does a white label Google Search sound so bad? Google has built an unrivaled index of the web, but the way it shows results has become increasingly frustrating. A handful of smaller players in search have tried to offer alternatives to Google’s search tools. They all have different approaches to retrieving information for you, but they agree that spinning off Google Search could change the web again. Whether or not those changes are positive depends on who you ask.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

A man with a severe speech disability is able to speak expressively and sing using a brain implant that translates his neural activity into words almost instantly. The device conveys changes of tone when he asks questions, emphasizes the words of his choice and allows him to hum a string of notes in three pitches.

A man with a severe speech disability is able to speak expressively and sing using a brain implant that translates his neural activity into words almost instantly. The device conveys changes of tone when he asks questions, emphasizes the words of his choice and allows him to hum a string of notes in three pitches. If you say Joe Criminal committed ten murders and five rapes, and I object that it was actually only six murders and two rapes, then why am I “defending” Joe Criminal?

If you say Joe Criminal committed ten murders and five rapes, and I object that it was actually only six murders and two rapes, then why am I “defending” Joe Criminal? There is a certain privilege in looking at a group of novels-in-translation from a single country originally written and published across almost a century. What appears at first glance to be a disparate assortment of texts gathered solely by the date of their reissue in a new language reveals an unexpected coherence. That the following five short Japanese novels-in-translation are being made available to a wider audience now, in the middle of the 2020s, feels timely.

There is a certain privilege in looking at a group of novels-in-translation from a single country originally written and published across almost a century. What appears at first glance to be a disparate assortment of texts gathered solely by the date of their reissue in a new language reveals an unexpected coherence. That the following five short Japanese novels-in-translation are being made available to a wider audience now, in the middle of the 2020s, feels timely. One of Jane Austen’s many mind-bending skills was her ability to wrest so much drama from a world that was, by present-day standards, almost unfathomably static. Austen’s novels are preindustrial time capsules from an era before even trains, gas lights, or telegraphs—the first in a stampede of inventions that transformed nineteenth-century life and are vividly present in the work of many novelists emblematic of that century. Born in 1775, a year before American Independence, Austen has preserved for us an epoch when indoor illumination required candles, remote communication took place by messenger or mail, and locomotion meant walking or engaging at least one horse—more if, like Emma’s protagonist and namesake (and indeed every woman in that novel), you didn’t ride, and needed a carriage to travel any distance.

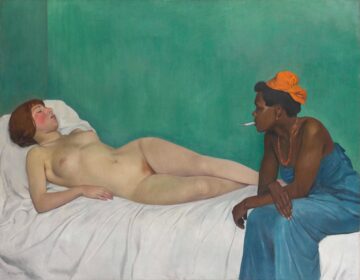

One of Jane Austen’s many mind-bending skills was her ability to wrest so much drama from a world that was, by present-day standards, almost unfathomably static. Austen’s novels are preindustrial time capsules from an era before even trains, gas lights, or telegraphs—the first in a stampede of inventions that transformed nineteenth-century life and are vividly present in the work of many novelists emblematic of that century. Born in 1775, a year before American Independence, Austen has preserved for us an epoch when indoor illumination required candles, remote communication took place by messenger or mail, and locomotion meant walking or engaging at least one horse—more if, like Emma’s protagonist and namesake (and indeed every woman in that novel), you didn’t ride, and needed a carriage to travel any distance. Sometimes it pays to spend more time in the detours of art history—leaving behind the rigor mortis of the canon to follow new pathways—not necessarily toward an alternative canon, but to discover forgotten artists deserving of more attention.

Sometimes it pays to spend more time in the detours of art history—leaving behind the rigor mortis of the canon to follow new pathways—not necessarily toward an alternative canon, but to discover forgotten artists deserving of more attention. In less than five years, we will have access to an error-free quantum supercomputer – so says IBM. The firm has presented a roadmap for building this machine, called Starling, slated to be available to researchers across academia and industry in 2029.

In less than five years, we will have access to an error-free quantum supercomputer – so says IBM. The firm has presented a roadmap for building this machine, called Starling, slated to be available to researchers across academia and industry in 2029. Consider the lessons of the Ukraine war so far. First, the impact of drones goes far beyond legacy weapons. Drones have indeed rendered tanks and armored personnel carriers extremely vulnerable, so Russian ground assaults now frequently use troops on foot, motorcycles, or all-terrain vehicles. But this hasn’t helped, because drones are terrifyingly effective against people as well. Casualties are as high as ever – but now, drones inflict

Consider the lessons of the Ukraine war so far. First, the impact of drones goes far beyond legacy weapons. Drones have indeed rendered tanks and armored personnel carriers extremely vulnerable, so Russian ground assaults now frequently use troops on foot, motorcycles, or all-terrain vehicles. But this hasn’t helped, because drones are terrifyingly effective against people as well. Casualties are as high as ever – but now, drones inflict  Condensing the history of Marxist thought

Condensing the history of Marxist thought The Wall is a story of an unnamed woman in her 40s who finds herself cut off from the rest of the world by the sudden appearance of the wall made of unknow material that separates a part of the forest from the rest of the world. This occurrence takes place during the narrator’s visit to her cousin, Luise’s and her husband, Hugo’s lodge in the Austrian Alps. She was unable to find an explanation for the appearance of the wall and was not sure if only the valley or the whole country had been affected by this disaster. Thanks to Hugo the narrator had provisions that would keep her through some time, and a lifetime’s supply of wood. that allowed her to survive. She also had their dog, Lynx who became an integral part of her new life along with two cats and the cow. They became her new family. At the time when the wall appeared the narrator was widowed for two years, and her two daughters were almost grown up.

The Wall is a story of an unnamed woman in her 40s who finds herself cut off from the rest of the world by the sudden appearance of the wall made of unknow material that separates a part of the forest from the rest of the world. This occurrence takes place during the narrator’s visit to her cousin, Luise’s and her husband, Hugo’s lodge in the Austrian Alps. She was unable to find an explanation for the appearance of the wall and was not sure if only the valley or the whole country had been affected by this disaster. Thanks to Hugo the narrator had provisions that would keep her through some time, and a lifetime’s supply of wood. that allowed her to survive. She also had their dog, Lynx who became an integral part of her new life along with two cats and the cow. They became her new family. At the time when the wall appeared the narrator was widowed for two years, and her two daughters were almost grown up. Benson was acerbic and often hilarious about other authors. He describes Henry James’s talk as boring but ‘intricate, magniloquent, rhetorical, humorous’, and quotes him as saying that ‘the difference between being with [J M] Barrie & not being with him was infinitesimal’. Asked whether any of the actresses introduced to him by Ellen Terry were pretty, James replied, ‘I must not go so far as to deny that one poor wanton had some species of cadaverous charm.’ Immensely fat, G K Chesterton got so hot at a Magdalene dinner that the sweat ran down his cigar and ‘hissed at the point’. Hilaire Belloc was scintillating but frowsy and tipsy, living in something like a ‘gypsy encampment’, which, Benson thought, should be burned to the ground. Accompanied by Edmund Gosse, Benson visited Thomas Hardy, whose features were ‘curiously worn & blurred & ruinous’; they might have belonged to ‘a retired half-pay officer, from a not very smart regiment’. Although admiring H G Wells, Benson deprecated his ‘strong cockney accent’ and his ‘glorification of animalism’.

Benson was acerbic and often hilarious about other authors. He describes Henry James’s talk as boring but ‘intricate, magniloquent, rhetorical, humorous’, and quotes him as saying that ‘the difference between being with [J M] Barrie & not being with him was infinitesimal’. Asked whether any of the actresses introduced to him by Ellen Terry were pretty, James replied, ‘I must not go so far as to deny that one poor wanton had some species of cadaverous charm.’ Immensely fat, G K Chesterton got so hot at a Magdalene dinner that the sweat ran down his cigar and ‘hissed at the point’. Hilaire Belloc was scintillating but frowsy and tipsy, living in something like a ‘gypsy encampment’, which, Benson thought, should be burned to the ground. Accompanied by Edmund Gosse, Benson visited Thomas Hardy, whose features were ‘curiously worn & blurred & ruinous’; they might have belonged to ‘a retired half-pay officer, from a not very smart regiment’. Although admiring H G Wells, Benson deprecated his ‘strong cockney accent’ and his ‘glorification of animalism’. C

C In 2023, one out of 20 Canadians who died received a physician-assisted death, making Canada the No. 1 provider of medical assistance in dying (MAID) in the world, when measured in total figures. In one province, Quebec, there were more MAID deaths per capita than anywhere else. Canadians, by and large, have been supportive of this trend. A 2022 poll showed that a stunning 86 percent of Canadians supported MAID’s legalization.

In 2023, one out of 20 Canadians who died received a physician-assisted death, making Canada the No. 1 provider of medical assistance in dying (MAID) in the world, when measured in total figures. In one province, Quebec, there were more MAID deaths per capita than anywhere else. Canadians, by and large, have been supportive of this trend. A 2022 poll showed that a stunning 86 percent of Canadians supported MAID’s legalization.