Leon Vlieger at The Inquisitive Biologist:

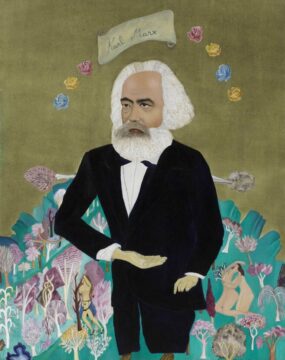

I have been promising/threatening for a while to cover degrowth, and thanks to a United States Society for Ecological Economics book club, now I will. In Less is More, economic anthropologist Jason Hickel identifies capitalism as the cause of our problems—the sort of criticism that makes many people really uncomfortable. Fortunately, he is an eloquent and charismatic spokesman who patiently but firmly walks you through the history of capitalism, exposes flaws of proposed fixes, and then lays out a litany of sensible solutions. It quickly confirms that sinking feeling most of us will have: that the economy is not working for us. What is perhaps eye-opening is that this is not by accident, but by design.

I have been promising/threatening for a while to cover degrowth, and thanks to a United States Society for Ecological Economics book club, now I will. In Less is More, economic anthropologist Jason Hickel identifies capitalism as the cause of our problems—the sort of criticism that makes many people really uncomfortable. Fortunately, he is an eloquent and charismatic spokesman who patiently but firmly walks you through the history of capitalism, exposes flaws of proposed fixes, and then lays out a litany of sensible solutions. It quickly confirms that sinking feeling most of us will have: that the economy is not working for us. What is perhaps eye-opening is that this is not by accident, but by design.

It helps, as Hickel quickly does, to clarify two things. First, he does not object to economic growth per se. Indeed, many of the world’s poorest countries need to grow further to meet basic human needs. The problem is growth for growth’s sake. In nature, growth is ubiquitous but normally follows a sigmoidal curve of some kind, eventually coming to a halt. Capitalism is different, which brings us to point two. People often confuse capitalism with markets and trade, but they pre-date capitalism by millennia. This is all textbook Marx, but, Hickel explains, markets and trade are organised around use-value: we trade for what is useful to us. Capitalism, on the other hand, is organised around exchange-value: goods are sold to make a profit, which is then reinvested to generate more profit. Growth is a structural imperative of capitalism: “It is a system that pulls ever-expanding quantities of nature and human labour into circuits of accumulation” (p. 40). The results are plain for all to see: environmental destruction and human immiseration benefitting a small minority.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

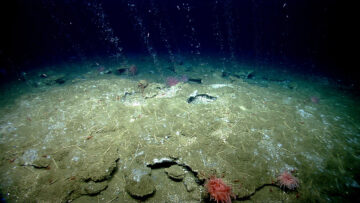

Buried in the deepest darkness underground, eating strange food, playing with the laws of thermodynamics and living on unrelatably long timescales, intraterrestrials have remained largely remote and aloof from humans. However, the microbes that dwell in the deep subsurface biosphere affect our lives in innumerable ways.

Buried in the deepest darkness underground, eating strange food, playing with the laws of thermodynamics and living on unrelatably long timescales, intraterrestrials have remained largely remote and aloof from humans. However, the microbes that dwell in the deep subsurface biosphere affect our lives in innumerable ways. The most conspicuous mark of Renata Adler’s style is its abundance of commas. In her two novels, Speedboat (1976) and Pitch Dark (1983), there are a few sentences that edge on the absurd: “For some time, Leander had spoken, on the phone, of a woman, a painter, whom he had met, one afternoon, outside the gym, and whom he was trying to introduce, along with Simon, into his apartment and his life.” A critic tallied it up, counting “40 words and ten commas—Guinness Book of World Records?” Each of those commas had its grammatical defense, but Adler’s style did not comply with the usual standards of fluent prose. She cordoned off phrases, such as “on the phone,” that other writers would just run through. One reader, responding to a 1983 New York magazine profile of Adler, wrote in a letter to the editor, “If the examples of Renata Adler’s writing … are typical, Miss Adler will never make it to the road. The way is ‘jarringly, piece by piece, line by line, and without interruption’ blocked by commas.” The reader was quoting one of Adler’s own comma-laden critical phrases against her. The editors titled the letter “Comma Wealth.”

The most conspicuous mark of Renata Adler’s style is its abundance of commas. In her two novels, Speedboat (1976) and Pitch Dark (1983), there are a few sentences that edge on the absurd: “For some time, Leander had spoken, on the phone, of a woman, a painter, whom he had met, one afternoon, outside the gym, and whom he was trying to introduce, along with Simon, into his apartment and his life.” A critic tallied it up, counting “40 words and ten commas—Guinness Book of World Records?” Each of those commas had its grammatical defense, but Adler’s style did not comply with the usual standards of fluent prose. She cordoned off phrases, such as “on the phone,” that other writers would just run through. One reader, responding to a 1983 New York magazine profile of Adler, wrote in a letter to the editor, “If the examples of Renata Adler’s writing … are typical, Miss Adler will never make it to the road. The way is ‘jarringly, piece by piece, line by line, and without interruption’ blocked by commas.” The reader was quoting one of Adler’s own comma-laden critical phrases against her. The editors titled the letter “Comma Wealth.” Not every rich person is rolling up in a Lamborghini or dripping in designer logos. If anything, the truly wealthy often move through the world a little quieter, but a lot more confidently. Look closely enough, and the signs are everywhere. Behavior is one of the first giveaways. Educator and content creator Dani Payne

Not every rich person is rolling up in a Lamborghini or dripping in designer logos. If anything, the truly wealthy often move through the world a little quieter, but a lot more confidently. Look closely enough, and the signs are everywhere. Behavior is one of the first giveaways. Educator and content creator Dani Payne  You can want different things from a university—superlative basketball, an arts center, competent instruction in philosophy or physics, even a cure for cancer. No wonder these institutions struggle to keep everyone happy. And everyone isn’t happy. The Trump Administration has effectively declared open war on higher education, targeting it with deep cuts to federal grant funding. University presidents are alarmed, as are faculty members, and anyone who cares about the university’s broader role.

You can want different things from a university—superlative basketball, an arts center, competent instruction in philosophy or physics, even a cure for cancer. No wonder these institutions struggle to keep everyone happy. And everyone isn’t happy. The Trump Administration has effectively declared open war on higher education, targeting it with deep cuts to federal grant funding. University presidents are alarmed, as are faculty members, and anyone who cares about the university’s broader role. A century ago, one of the richest men in the world decided to wade into the public sphere by throwing his weight behind a series of cuts that would reach into every corner of American life. The president of the day, sensing early support for these reforms and not wishing to be left behind, jumped on board with impulsive zeal, demanding that all federal offices implement the cutbacks with immediate effect.

A century ago, one of the richest men in the world decided to wade into the public sphere by throwing his weight behind a series of cuts that would reach into every corner of American life. The president of the day, sensing early support for these reforms and not wishing to be left behind, jumped on board with impulsive zeal, demanding that all federal offices implement the cutbacks with immediate effect.

The legal doctrine of “habeas corpus,” a Latin phrase that has its

The legal doctrine of “habeas corpus,” a Latin phrase that has its  What’s distinctive about humans is that homo sapiens domesticated themselves. We are self-domesticated apes. Anthropologist Brian Hare characterizes recent human evolution (Late Pleistocene) as “Survival of the Friendliest”, arguing that in our self-domestication we favored prosociality — the tendency to be friendly, cooperative, and empathetic. We chose the most cooperative, the least aggressive, the less bullying types, and that trust in others resulted in greater prosperity, which in turn spread neoteny genes, and other domestication traits, into our populations.

What’s distinctive about humans is that homo sapiens domesticated themselves. We are self-domesticated apes. Anthropologist Brian Hare characterizes recent human evolution (Late Pleistocene) as “Survival of the Friendliest”, arguing that in our self-domestication we favored prosociality — the tendency to be friendly, cooperative, and empathetic. We chose the most cooperative, the least aggressive, the less bullying types, and that trust in others resulted in greater prosperity, which in turn spread neoteny genes, and other domestication traits, into our populations. Against the backdrop of a cold white room, Iris Apfel’s yellow outfit, which she wore on the occasion of her hundredth birthday, sings its own joyous song. Both here and elsewhere, Apfel, an artist and fashion designer, often paired gorgeous things sensually by color and texture, rather than by invoking some obvious theory or idea. She was not afraid to wear a yellow tulle coat with yellow silk pants (which she designed herself in collaboration with H&M). She celebrated yellow vivaciously; she took up space with yellow. With her arms raised in this picture, she looks like some sort of bishop or religious figure. Her open palms throw spectral glitter upon us. A spiritual icon. Just by looking at her, I feel her upturned palms manifesting my dreams.

Against the backdrop of a cold white room, Iris Apfel’s yellow outfit, which she wore on the occasion of her hundredth birthday, sings its own joyous song. Both here and elsewhere, Apfel, an artist and fashion designer, often paired gorgeous things sensually by color and texture, rather than by invoking some obvious theory or idea. She was not afraid to wear a yellow tulle coat with yellow silk pants (which she designed herself in collaboration with H&M). She celebrated yellow vivaciously; she took up space with yellow. With her arms raised in this picture, she looks like some sort of bishop or religious figure. Her open palms throw spectral glitter upon us. A spiritual icon. Just by looking at her, I feel her upturned palms manifesting my dreams. T

T What Rina Green calls her “living hell” began with an innocuous backache. By late 2022, two years later,

What Rina Green calls her “living hell” began with an innocuous backache. By late 2022, two years later,  L

L