Tanner Greer at The Scholar’s Stage:

Harold Bloom is dead. His death has prompted one final, staggered brawl between the exhausted ranks who have spent away their strength with three decades of culture warring. My personal assessment of Bloom is that he was an excellent salesman and a stupendous reader, but an uninspired critic. With the concept of a ‘canon’ or a ‘classic’ I have no argument. It seems obvious to me that some works are better than others and more obvious still that if a book is still being read several centuries after it was written it is likely one of those better works–or barring that, a work whose intellectual or artistic legacy makes it a necessary piece of the larger puzzle. The trouble with Bloom was not his elephant love for the canon, but his inability to articulate anything but this passion (and disgust with those who sought to defile it). The truth is that Bloom adds nothing to the great works he champions. This weakness is seen most clearly in his many volumes on Shakespeare; in less exaggerated form it mars the judgments Bloom throws around in The Western Canon or Genius.

Bloom declares where he should argue, emotes where he should analyze, and effuses where he should unveil. Bloom deplored young Hal to the center of his bones; his love for Falstaff soaked through his soul down into his toes. You’ll discover this within a minute of reading any of Bloom’s criticism of the Bard.

More here.

IT’S NOT QUITE CLEAR

IT’S NOT QUITE CLEAR Michael Kimmelman, architecture critic at the New York Times, calls the new design ‘smart, surgical, sprawling and slightly soulless’. I would take ‘slightly soulless’ over ‘aggressively spectacular’, and given the political controversies visited on other museums due to their problematic mega-donors (the opioid Sackler family, the anarcho-libertarian Koch brothers, the police-weapon magnate Warren Kanders, and other bad actors), such a review counts as a rave. And by and large the new MoMA is a success. Of course, there are some missteps. The walls darken in the Surrealist galleries, as though to warn us, through mood control, that here modernism plunges into the unconscious. The new MoMA is more open to campy artists like Florine Stettheimer, brutish figures like Jean Dubuffet, and erotic fantasists like Hans Bellmer, but it is still rather reserved about overtly political artists, whether of the right or the left (revolutionary Russians stand in for many others). And though the intermedial presentation of film and photography is an advance, the lived history of these media, as registered in a noisy projector or an old magazine, is mostly lost – the contemplative rituals of painting still predominate, albeit not as much as before. Apart from a magnificent array of Brancusi sculptures, which introduces the fifth floor, a forceful mix of Post-Minimalist objects, which opens the fourth floor, and the Serra installation, which lends needed gravitas to the contemporary galleries, sculpture is still treated as secondary.

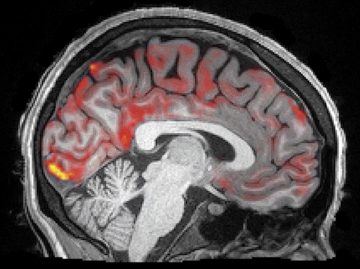

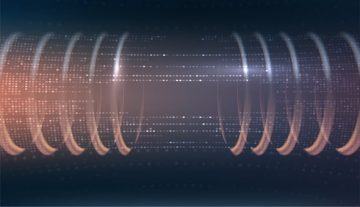

Michael Kimmelman, architecture critic at the New York Times, calls the new design ‘smart, surgical, sprawling and slightly soulless’. I would take ‘slightly soulless’ over ‘aggressively spectacular’, and given the political controversies visited on other museums due to their problematic mega-donors (the opioid Sackler family, the anarcho-libertarian Koch brothers, the police-weapon magnate Warren Kanders, and other bad actors), such a review counts as a rave. And by and large the new MoMA is a success. Of course, there are some missteps. The walls darken in the Surrealist galleries, as though to warn us, through mood control, that here modernism plunges into the unconscious. The new MoMA is more open to campy artists like Florine Stettheimer, brutish figures like Jean Dubuffet, and erotic fantasists like Hans Bellmer, but it is still rather reserved about overtly political artists, whether of the right or the left (revolutionary Russians stand in for many others). And though the intermedial presentation of film and photography is an advance, the lived history of these media, as registered in a noisy projector or an old magazine, is mostly lost – the contemplative rituals of painting still predominate, albeit not as much as before. Apart from a magnificent array of Brancusi sculptures, which introduces the fifth floor, a forceful mix of Post-Minimalist objects, which opens the fourth floor, and the Serra installation, which lends needed gravitas to the contemporary galleries, sculpture is still treated as secondary. The brain waves generated during deep sleep appear to trigger a cleaning system in the brain that protects it against Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases.

The brain waves generated during deep sleep appear to trigger a cleaning system in the brain that protects it against Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases. “What would your feelings be,” asks Ambrose in Arthur Machen’s novel The House of Souls, “… if your cat or your dog began to talk to you, and to dispute with you in human accents?” He goes on:

“What would your feelings be,” asks Ambrose in Arthur Machen’s novel The House of Souls, “… if your cat or your dog began to talk to you, and to dispute with you in human accents?” He goes on: K

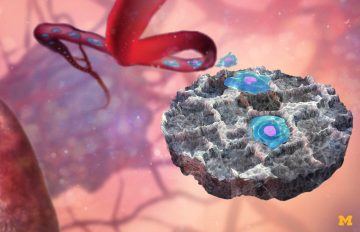

K ANN ARBOR—Invasive procedures to biopsy tissue from cancer-tainted organs could be replaced by simply taking samples from a tiny “decoy” implanted just beneath the skin, University of Michigan researchers have demonstrated in mice. These devices have a knack for attracting cancer cells traveling through the body. In fact, they can even pick up signs that cancer is preparing to spread, before cancer cells arrive. “Biopsying an organ like the lung is a risky procedure that’s done only sparingly,” said Lonnie Shea, the William and Valerie Hall Chair of biomedical engineering at U-M. “We place these scaffolds right under the skin, so they’re readily accessible.”

ANN ARBOR—Invasive procedures to biopsy tissue from cancer-tainted organs could be replaced by simply taking samples from a tiny “decoy” implanted just beneath the skin, University of Michigan researchers have demonstrated in mice. These devices have a knack for attracting cancer cells traveling through the body. In fact, they can even pick up signs that cancer is preparing to spread, before cancer cells arrive. “Biopsying an organ like the lung is a risky procedure that’s done only sparingly,” said Lonnie Shea, the William and Valerie Hall Chair of biomedical engineering at U-M. “We place these scaffolds right under the skin, so they’re readily accessible.” John Rawls, who died in 2002, was the most influential American philosopher of the twentieth century. His great work,

John Rawls, who died in 2002, was the most influential American philosopher of the twentieth century. His great work,  In the lowlands of Bolivia, the most isolated of the Tsimané people live in communities without electricity; they don’t own televisions, computers or phones, and even battery-powered radios are rare. Their minimal exposure to Western culture happens mostly during occasional trips to nearby towns. To the researchers who make their way into Tsimané villages by truck and canoe each summer, that isolation makes the Tsimané an almost uniquely valuable source of insights into the human brain and its processing of music.

In the lowlands of Bolivia, the most isolated of the Tsimané people live in communities without electricity; they don’t own televisions, computers or phones, and even battery-powered radios are rare. Their minimal exposure to Western culture happens mostly during occasional trips to nearby towns. To the researchers who make their way into Tsimané villages by truck and canoe each summer, that isolation makes the Tsimané an almost uniquely valuable source of insights into the human brain and its processing of music. In July 2011, a quiet European capital was shaken by a terrorist car bomb, followed by confused reports suggesting many deaths. When the first news of the murders came through, one small group of online commentators reacted immediately, even though the media had cautiously declined to identify the attackers. They knew at once what had happened – and who was to blame.

In July 2011, a quiet European capital was shaken by a terrorist car bomb, followed by confused reports suggesting many deaths. When the first news of the murders came through, one small group of online commentators reacted immediately, even though the media had cautiously declined to identify the attackers. They knew at once what had happened – and who was to blame. A pair of recent essay collections—Jia Tolentino’s

A pair of recent essay collections—Jia Tolentino’s  In a preface to her ghost stories, Wharton writes, “I do not believe in ghosts, but I am afraid of them.” Following an attack of typhoid as a child, Wharton writes in her autobiography, A Backward Glance, that she returned from the brink of death with “chronic fear” that felt like a “choking agony of terror.” Well into young adulthood, she would not sleep without a light and a maid present in her room. “It was like some dark, indefinable menace, forever dogging my steps, lurking, and threatening,” she writes, and I could not help but think of Hilary Mantel’s childhood encounter with an indescribable evil in her family’s garden. Must all women be visited by terror so consistently and from such a young age? The rumors of paranormal activity at the Mount began after the house become an all-girls school in the forties, and intensified when the theater troupe Shakespeare and Company took residence there in the seventies. The performers were kicked out more than a decade ago in a landlord-tenant dispute that seemed, publicly, not related to the supernatural. Even so, nothing attracts the devil more than a group of adolescent girls, except for maybe a group of actors.

In a preface to her ghost stories, Wharton writes, “I do not believe in ghosts, but I am afraid of them.” Following an attack of typhoid as a child, Wharton writes in her autobiography, A Backward Glance, that she returned from the brink of death with “chronic fear” that felt like a “choking agony of terror.” Well into young adulthood, she would not sleep without a light and a maid present in her room. “It was like some dark, indefinable menace, forever dogging my steps, lurking, and threatening,” she writes, and I could not help but think of Hilary Mantel’s childhood encounter with an indescribable evil in her family’s garden. Must all women be visited by terror so consistently and from such a young age? The rumors of paranormal activity at the Mount began after the house become an all-girls school in the forties, and intensified when the theater troupe Shakespeare and Company took residence there in the seventies. The performers were kicked out more than a decade ago in a landlord-tenant dispute that seemed, publicly, not related to the supernatural. Even so, nothing attracts the devil more than a group of adolescent girls, except for maybe a group of actors. Does the ferocity of the Brexit debate reveal different conceptions of the nature and value of democracy? Brexiteers proudly talk as if the 2016 vote was a rare paradigm of real democracy – “the largest democratic exercise in our history” – while Remainers respond that majority voting by the electorate is only a small part of our democratic system. In a representative democracy, our elected representatives can and should scrutinize the result of an “advisory” referendum as they scrutinize anything else. So why should a referendum result be “respected” if the democratically elected politicians were to decide that, all things considered, it is not in the country’s best interests? On the other hand, Brexiteers will respond that if parliament can overturn the result, what was the point of the referendum in the first place?

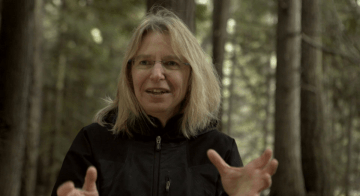

Does the ferocity of the Brexit debate reveal different conceptions of the nature and value of democracy? Brexiteers proudly talk as if the 2016 vote was a rare paradigm of real democracy – “the largest democratic exercise in our history” – while Remainers respond that majority voting by the electorate is only a small part of our democratic system. In a representative democracy, our elected representatives can and should scrutinize the result of an “advisory” referendum as they scrutinize anything else. So why should a referendum result be “respected” if the democratically elected politicians were to decide that, all things considered, it is not in the country’s best interests? On the other hand, Brexiteers will respond that if parliament can overturn the result, what was the point of the referendum in the first place? Consider a forest: One notices the trunks, of course, and the canopy. If a few roots project artfully above the soil and fallen leaves, one notices those too, but with little thought for a matrix that may spread as deep and wide as the branches above. Fungi don’t register at all except for a sprinkling of mushrooms; those are regarded in isolation, rather than as the fruiting tips of a vast underground lattice intertwined with those roots. The world beneath the earth is as rich as the one above. For the past two decades, Suzanne Simard, a professor in the Department of Forest & Conservation at the University of British Columbia, has studied that unappreciated underworld. Her specialty is mycorrhizae: the symbiotic unions of fungi and root long known to help plants absorb nutrients from soil. Beginning with landmark experiments describing how carbon flowed between paper birch and Douglas fir trees, Simard found that mycorrhizae didn’t just connect trees to the earth, but to each other as well.

Consider a forest: One notices the trunks, of course, and the canopy. If a few roots project artfully above the soil and fallen leaves, one notices those too, but with little thought for a matrix that may spread as deep and wide as the branches above. Fungi don’t register at all except for a sprinkling of mushrooms; those are regarded in isolation, rather than as the fruiting tips of a vast underground lattice intertwined with those roots. The world beneath the earth is as rich as the one above. For the past two decades, Suzanne Simard, a professor in the Department of Forest & Conservation at the University of British Columbia, has studied that unappreciated underworld. Her specialty is mycorrhizae: the symbiotic unions of fungi and root long known to help plants absorb nutrients from soil. Beginning with landmark experiments describing how carbon flowed between paper birch and Douglas fir trees, Simard found that mycorrhizae didn’t just connect trees to the earth, but to each other as well. Justin E. H. Smith is a professor of history and philosophy of science at the University of Paris. In addition to his recent book,

Justin E. H. Smith is a professor of history and philosophy of science at the University of Paris. In addition to his recent book,  If you could look closely enough at the objects that surround you, zooming in at magnifications far beyond those you could ever see with most microscopes, you would eventually get to a point where the familiar rules of your everyday experiences break down. At scales where blood cells and viruses seem enormous and molecules come into view, things are no longer subject to the simple laws of physics that we learn in high school.

If you could look closely enough at the objects that surround you, zooming in at magnifications far beyond those you could ever see with most microscopes, you would eventually get to a point where the familiar rules of your everyday experiences break down. At scales where blood cells and viruses seem enormous and molecules come into view, things are no longer subject to the simple laws of physics that we learn in high school.