Isabella Hammad in The Yale Review:

A few years ago, I taught the Lebanese American writer and artist Etel Adnan’s short novel, Sitt Marie-Rose (1978), as part of an undergraduate literature class in the Occupied West Bank. Composed in French over a single month (“end to end,” Adnan said) in 1976, Sitt Marie-Rose tells a fictional version of the story of Marie-Rose Boulos, a Syrian Christian woman kidnapped and killed for helping the Palestinians during the first phase of the Lebanese Civil War, which began in 1975. The book was among the class’s favorite texts on the syllabus, and when I asked why they liked it so much, one student raised his hand and replied: “She said what needed to be said.”

A few years ago, I taught the Lebanese American writer and artist Etel Adnan’s short novel, Sitt Marie-Rose (1978), as part of an undergraduate literature class in the Occupied West Bank. Composed in French over a single month (“end to end,” Adnan said) in 1976, Sitt Marie-Rose tells a fictional version of the story of Marie-Rose Boulos, a Syrian Christian woman kidnapped and killed for helping the Palestinians during the first phase of the Lebanese Civil War, which began in 1975. The book was among the class’s favorite texts on the syllabus, and when I asked why they liked it so much, one student raised his hand and replied: “She said what needed to be said.”

Over the course of the past year, my reading habits have narrowed. As Israel’s genocidal war on the Palestinians in Gaza expanded to Lebanon with the complicity and support of many of the world’s great powers, I found myself passing over books that failed to offer me a route into thinking about the great brutality of the period through which we are living.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

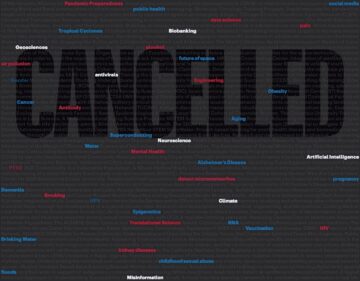

It is almost certainly the most consequential 100 days that scientists in the United States have experienced since the end of World War II.

It is almost certainly the most consequential 100 days that scientists in the United States have experienced since the end of World War II. On October 6, 1973, Pramoedya Ananta Toer was ordered by prison guards to run double-time across Buru Island. The writer had been arrested eight years before, taken into custody in the middle of the night. Detained without charges alongside thousands of other men and women, Toer was sent to Buru—a prison island far east of Java and Bali—and forced to toil under the scorching sun. He was desolate, not only because of the Sisyphean labor he was made to perform, the inability to write, and the gnawing feeling of injustice, but also because he was separated from his family. Before prison, he had been happily married to his beloved Maimoenah, his second wife and mother to five of his children. After several years of seclusion from the outside world, Toer was hopeful that the press junket he was being forced to attend could be an opportunity to petition for the freedoms that had been revoked when he was imprisoned, if not ensure his release. It would be the closest he would get to a trial, during which he could publicly question the validity of his arrest.

On October 6, 1973, Pramoedya Ananta Toer was ordered by prison guards to run double-time across Buru Island. The writer had been arrested eight years before, taken into custody in the middle of the night. Detained without charges alongside thousands of other men and women, Toer was sent to Buru—a prison island far east of Java and Bali—and forced to toil under the scorching sun. He was desolate, not only because of the Sisyphean labor he was made to perform, the inability to write, and the gnawing feeling of injustice, but also because he was separated from his family. Before prison, he had been happily married to his beloved Maimoenah, his second wife and mother to five of his children. After several years of seclusion from the outside world, Toer was hopeful that the press junket he was being forced to attend could be an opportunity to petition for the freedoms that had been revoked when he was imprisoned, if not ensure his release. It would be the closest he would get to a trial, during which he could publicly question the validity of his arrest. A

A At its heart, cricket stands as a wonderfully pastoral exercise in deferred gratification. Today, there are various forms of the sport around the world, but to most purists its true and highest expression lies in the international, or “test,” match, involving, say, England playing Australia or India facing Pakistan. Such encounters typically last five full days, with roughly eight hours of actual sport each day and the contestants communally decamping to a hotel each evening and returning to pick up where they left off the following morning. Twice a day, the same players leave the field and stroll back to the pavilion, or clubhouse, for a good meal, and on the warmer afternoons—rarely an issue during matches in England—a uniformed attendant will periodically appear on the field bearing a tray of assorted refreshments. Just to give you a sense of the essentially unhurried nature of the enterprise, a single batter can remain at his post for several hours, if not entire days, on end, and, if sufficiently skillful, accrue upwards of one hundred individual runs before being dismissed. In another of cricket’s cherished rituals, he can expect to be warmly applauded by his opponents on reaching such a milestone.

At its heart, cricket stands as a wonderfully pastoral exercise in deferred gratification. Today, there are various forms of the sport around the world, but to most purists its true and highest expression lies in the international, or “test,” match, involving, say, England playing Australia or India facing Pakistan. Such encounters typically last five full days, with roughly eight hours of actual sport each day and the contestants communally decamping to a hotel each evening and returning to pick up where they left off the following morning. Twice a day, the same players leave the field and stroll back to the pavilion, or clubhouse, for a good meal, and on the warmer afternoons—rarely an issue during matches in England—a uniformed attendant will periodically appear on the field bearing a tray of assorted refreshments. Just to give you a sense of the essentially unhurried nature of the enterprise, a single batter can remain at his post for several hours, if not entire days, on end, and, if sufficiently skillful, accrue upwards of one hundred individual runs before being dismissed. In another of cricket’s cherished rituals, he can expect to be warmly applauded by his opponents on reaching such a milestone. Yu, now an associate professor at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), is a leader in a field known as “physics-guided deep learning,” having spent years incorporating our knowledge of physics into artificial neural networks. The work has not only introduced novel techniques for building and training these systems, but it’s also allowed her to make progress on several real-world applications. She has drawn on principles of fluid dynamics to improve traffic predictions, sped up simulations of turbulence to enhance our understanding of hurricanes and devised tools that helped predict the spread of Covid-19.

Yu, now an associate professor at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), is a leader in a field known as “physics-guided deep learning,” having spent years incorporating our knowledge of physics into artificial neural networks. The work has not only introduced novel techniques for building and training these systems, but it’s also allowed her to make progress on several real-world applications. She has drawn on principles of fluid dynamics to improve traffic predictions, sped up simulations of turbulence to enhance our understanding of hurricanes and devised tools that helped predict the spread of Covid-19. One of the most interesting films on Netflix is

One of the most interesting films on Netflix is  In just the first three months of his second term, US President Donald Trump has destabilized eight decades of government support for science. His administration has fired thousands of government scientists, bringing large swathes of the country’s research to a standstill and halting many clinical trials. It has threatened to

In just the first three months of his second term, US President Donald Trump has destabilized eight decades of government support for science. His administration has fired thousands of government scientists, bringing large swathes of the country’s research to a standstill and halting many clinical trials. It has threatened to  Carney’s win, and it is his win, began long before the writs were issued. In January, the Liberal Party, under Justin Trudeau, was thoroughly cooked and was well on its way to defeat for months. A movement to oust Trudeau had begun earlier, but it wasn’t until Chrystia Freeland, former finance minister and deputy prime minister who was about to be shuffled out of her coveted job, quit the cabinet altogether in mid-December that Trudeau’s fate was

Carney’s win, and it is his win, began long before the writs were issued. In January, the Liberal Party, under Justin Trudeau, was thoroughly cooked and was well on its way to defeat for months. A movement to oust Trudeau had begun earlier, but it wasn’t until Chrystia Freeland, former finance minister and deputy prime minister who was about to be shuffled out of her coveted job, quit the cabinet altogether in mid-December that Trudeau’s fate was  It must be emphasised that until recently, the story of African philosophy has been synonymous with unjustified denial, exclusion, controversy, and scepticism. Thus, within the first chapter, Mungwini carefully provides an excellent cartographic analysis of the discipline of African philosophy before exposing some of the debates, challenges, disagreements and controversies that have historically characterised and shaped the development and current trends in African philosophy, particularly the famous “critique of ethnophilosophy” that was sparked by Paulin J. Hountondji. While he strives to “lay out its [African philosophy’s] methodological and epistemological foundations as an enterprise” (17), Mungwini makes an important entry into African philosophy. He identifies the kind of self-scepticism and hesitancy to affirm self-identity that impedes the progress of African philosophy owing to the critique of ethnophilosophy, unlike the “multiplicity of views and divisions that have characterised Western philosophy as a tradition” (14; see also, 18). Essentially, Mungwini alerts the reader to some of the consequences of the unintended exclusionary effects which the traditional critique of ethno-philosophy has had on African philosophical traditions, notwithstanding its encouragement of critical discourse on African philosophy through rejection of what Mungwini sees as unanimism and extraversion (24). Indeed, the critique of ethno-philosophy can be acknowledged for denying a collective philosophy that is always oriented towards satisfying the outside world, although, its putative implications on African philosophy is something that cannot be taken for granted, and Mungwini should be credited for his cautionary approach to it.

It must be emphasised that until recently, the story of African philosophy has been synonymous with unjustified denial, exclusion, controversy, and scepticism. Thus, within the first chapter, Mungwini carefully provides an excellent cartographic analysis of the discipline of African philosophy before exposing some of the debates, challenges, disagreements and controversies that have historically characterised and shaped the development and current trends in African philosophy, particularly the famous “critique of ethnophilosophy” that was sparked by Paulin J. Hountondji. While he strives to “lay out its [African philosophy’s] methodological and epistemological foundations as an enterprise” (17), Mungwini makes an important entry into African philosophy. He identifies the kind of self-scepticism and hesitancy to affirm self-identity that impedes the progress of African philosophy owing to the critique of ethnophilosophy, unlike the “multiplicity of views and divisions that have characterised Western philosophy as a tradition” (14; see also, 18). Essentially, Mungwini alerts the reader to some of the consequences of the unintended exclusionary effects which the traditional critique of ethno-philosophy has had on African philosophical traditions, notwithstanding its encouragement of critical discourse on African philosophy through rejection of what Mungwini sees as unanimism and extraversion (24). Indeed, the critique of ethno-philosophy can be acknowledged for denying a collective philosophy that is always oriented towards satisfying the outside world, although, its putative implications on African philosophy is something that cannot be taken for granted, and Mungwini should be credited for his cautionary approach to it. When I first moved to Salzburg, I rented a place in a small 19th century building around the corner from the medieval Linzer Gasse, where Renaissance polymath Dr. Paracelsus was buried, and where Expressionist poet Georg Trakl had worked in a pharmacy. The flat had high ceilings, tall windows, a lovely old herringbone wooden floor, and blinding white walls just waiting for works of graphic impact to give them a semblance of meaning. I couldn’t afford a painting, but in a nearby poster shop—they were popular in those pre-online days—I flipped through hundreds of art reproductions, hoping to find an image deserving of those pristine walls. Only one poster fit the bill: a László Moholy-Nagy collage from 1922: Kinetisch-Konstruktives System (KKS).

When I first moved to Salzburg, I rented a place in a small 19th century building around the corner from the medieval Linzer Gasse, where Renaissance polymath Dr. Paracelsus was buried, and where Expressionist poet Georg Trakl had worked in a pharmacy. The flat had high ceilings, tall windows, a lovely old herringbone wooden floor, and blinding white walls just waiting for works of graphic impact to give them a semblance of meaning. I couldn’t afford a painting, but in a nearby poster shop—they were popular in those pre-online days—I flipped through hundreds of art reproductions, hoping to find an image deserving of those pristine walls. Only one poster fit the bill: a László Moholy-Nagy collage from 1922: Kinetisch-Konstruktives System (KKS). In the decade that I have been working on AI, I’ve watched it grow from a tiny academic field to arguably the most important economic and geopolitical issue in the world. In all that time, perhaps the most important lesson I’ve learned is this: the progress of the underlying technology is inexorable, driven by forces too powerful to stop, but the way in which it happens—the order in which things are built, the applications we choose, and the details of how it is rolled out to society—are eminently possible to change, and it’s possible to have great positive impact by doing so. We can’t stop the bus, but we can steer it. In the past I’ve written about the importance of deploying AI in a way that is

In the decade that I have been working on AI, I’ve watched it grow from a tiny academic field to arguably the most important economic and geopolitical issue in the world. In all that time, perhaps the most important lesson I’ve learned is this: the progress of the underlying technology is inexorable, driven by forces too powerful to stop, but the way in which it happens—the order in which things are built, the applications we choose, and the details of how it is rolled out to society—are eminently possible to change, and it’s possible to have great positive impact by doing so. We can’t stop the bus, but we can steer it. In the past I’ve written about the importance of deploying AI in a way that is  I have been promising/threatening for a while to cover degrowth, and thanks to a

I have been promising/threatening for a while to cover degrowth, and thanks to a