Johanna Thomas-Corr in The Guardian:

Ian McEwan once wrote: “When women stop reading, the novel will be dead.” Back in 2005, he and his son culled the library of his London house and took stacks of books to a local park to give away. He said every woman he approached asked for three, whereas every man “frowned in suspicion, or distaste” and usually said something like: “‘Nah, nah. Not for me. Thanks, mate, but no.’” The history of fiction has always been a history of women readers. From the 18th century, the novel itself was aimed at a new class of leisured women, who didn’t receive formal education in science or politics. The male writers and critics who wrote and appraised the first novels legitimised the form, but Taylor says they “were quickly overtaken by women writers of sensation and romance fiction. Women took to it as a way of learning about other lives, fantasising about their own relationships and narratives that allowed them to challenge their own subordinate position to men.”

Ian McEwan once wrote: “When women stop reading, the novel will be dead.” Back in 2005, he and his son culled the library of his London house and took stacks of books to a local park to give away. He said every woman he approached asked for three, whereas every man “frowned in suspicion, or distaste” and usually said something like: “‘Nah, nah. Not for me. Thanks, mate, but no.’” The history of fiction has always been a history of women readers. From the 18th century, the novel itself was aimed at a new class of leisured women, who didn’t receive formal education in science or politics. The male writers and critics who wrote and appraised the first novels legitimised the form, but Taylor says they “were quickly overtaken by women writers of sensation and romance fiction. Women took to it as a way of learning about other lives, fantasising about their own relationships and narratives that allowed them to challenge their own subordinate position to men.”

Though there have been histories of women’s reading, Taylor’s spirited, engaging study is the first that tries to capture how fiction matters to contemporary women of different ages, classes and ethnic groups. She says that when she tells men the title of her book, they get defensive. “They say, ‘But I read fiction too!’ I say, ‘I’m sure that’s true, but far fewer men do.’ When I scratch beneath the surface to find out why they have read a certain novel, they never give me an emotional answer. It’s always: ‘Well, it’s because I’m very interested in stories about the first world war or the Victorian period.’ Or they say they did history at university and want to follow up certain ideas. Or that they quite like to read Martin Amis because his characters are funny.”

More here.

Associate Professor Roger Pocock, from the Monash Biomedicine Discovery Institute (BDI), and colleagues from the University of Cambridge led by Professor David Rubinsztein, found that microRNAs are important in controlling

Associate Professor Roger Pocock, from the Monash Biomedicine Discovery Institute (BDI), and colleagues from the University of Cambridge led by Professor David Rubinsztein, found that microRNAs are important in controlling  Steven Shapin in the LA Review of Books:

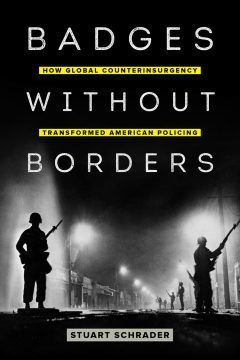

Steven Shapin in the LA Review of Books: Patrick Blanchfield in Bookforum:

Patrick Blanchfield in Bookforum: Quinn Slobodian in The Guardian:

Quinn Slobodian in The Guardian: Mistress Snow in The Chronicle Review:

Mistress Snow in The Chronicle Review: B

B Reading The Dry Heart is like listening to a person confess in half-truths. The second time the narrator revisits killing Alberto, she describes how she prepared him a thermos of tea with milk and sugar before pulling his revolver out of his desk. The third time, she reveals that he was packing his bags for a trip; that she suspected he was not traveling alone; and that when she told him she would “rather know the truth, whatever it may be,” he replied by misquoting Dante’s Purgatorio: “She seeketh Truth, which is so dear / As knoweth he who life for her refuses.”

Reading The Dry Heart is like listening to a person confess in half-truths. The second time the narrator revisits killing Alberto, she describes how she prepared him a thermos of tea with milk and sugar before pulling his revolver out of his desk. The third time, she reveals that he was packing his bags for a trip; that she suspected he was not traveling alone; and that when she told him she would “rather know the truth, whatever it may be,” he replied by misquoting Dante’s Purgatorio: “She seeketh Truth, which is so dear / As knoweth he who life for her refuses.” I

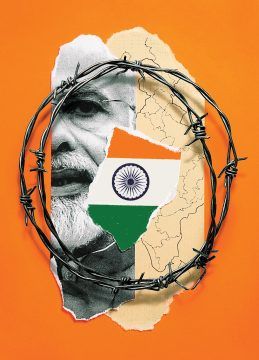

I In August of this year, Prime Minister Narendra Modi of India suspended Article 370 of the constitution, the provision that granted some level of autonomy to

In August of this year, Prime Minister Narendra Modi of India suspended Article 370 of the constitution, the provision that granted some level of autonomy to  Englishness was always a form of theatre, first staged in overseas colonies. Discovering its traces in Rudyard Kipling and India, VS Naipaul remarked on how, “at the height of their power, the British gave the impression of a people at play, a people playing at being English, playing at being English of a certain class”. Today, in a post-imperial Britain run by half-witted public schoolboys, the English character seems even more, as Naipaul wrote, “a creation of fantasy”.

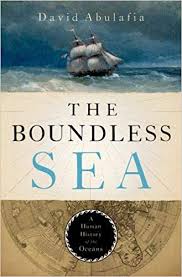

Englishness was always a form of theatre, first staged in overseas colonies. Discovering its traces in Rudyard Kipling and India, VS Naipaul remarked on how, “at the height of their power, the British gave the impression of a people at play, a people playing at being English, playing at being English of a certain class”. Today, in a post-imperial Britain run by half-witted public schoolboys, the English character seems even more, as Naipaul wrote, “a creation of fantasy”. We’re on Flatey, a small island in an archipelago in West Iceland. These islands are clustered in Breiðafjörður, a fjord that Icelanders often talk about in metaphorical terms: “Their freckles were as countless as the islands in Breiðafjörður.” We write this in June, when the sun never forsakes the sky, and half of the island is closed off because it’s nesting season. There are birds everywhere.

We’re on Flatey, a small island in an archipelago in West Iceland. These islands are clustered in Breiðafjörður, a fjord that Icelanders often talk about in metaphorical terms: “Their freckles were as countless as the islands in Breiðafjörður.” We write this in June, when the sun never forsakes the sky, and half of the island is closed off because it’s nesting season. There are birds everywhere. This reliance on models has always been a bête noire for climate change deniers, who have questioned their accuracy as a way of casting doubt on their dire projections. For years, it has been a running battle between scientists and their critics, with the former rallying to defend one dataset and model after another. (The invaluable site Skeptical Science has a

This reliance on models has always been a bête noire for climate change deniers, who have questioned their accuracy as a way of casting doubt on their dire projections. For years, it has been a running battle between scientists and their critics, with the former rallying to defend one dataset and model after another. (The invaluable site Skeptical Science has a  On August 11th, two weeks after Prime Minister Narendra Modi sent soldiers in to pacify the Indian state of Kashmir, a reporter appeared on the news channel Republic TV, riding a motor scooter through the city of Srinagar. She was there to assure viewers that, whatever else they might be hearing, the situation was remarkably calm. “You can see banks here and commercial complexes,” the reporter, Sweta Srivastava, said, as she wound her way past local landmarks. “The situation makes you feel good, because the situation is returning to normal, and the locals are ready to live their lives normally again.” She conducted no interviews; there was no one on the streets to talk to.

On August 11th, two weeks after Prime Minister Narendra Modi sent soldiers in to pacify the Indian state of Kashmir, a reporter appeared on the news channel Republic TV, riding a motor scooter through the city of Srinagar. She was there to assure viewers that, whatever else they might be hearing, the situation was remarkably calm. “You can see banks here and commercial complexes,” the reporter, Sweta Srivastava, said, as she wound her way past local landmarks. “The situation makes you feel good, because the situation is returning to normal, and the locals are ready to live their lives normally again.” She conducted no interviews; there was no one on the streets to talk to. Wood points out that contemporary image-based culture — the profusion he can barely sum up by listing “advertising, fashion, celebrities, television, tattoos, toys, comics, pornography, politics, iPhones, and stuff in general” — is impossible for art history to grasp, even though it is to a great extent the content of contemporary art. But his belief that today’s art “is no longer preoccupied with form” is one that would hardly be accepted by most artists or anyone else who is involved in contemporary art on a daily basis.

Wood points out that contemporary image-based culture — the profusion he can barely sum up by listing “advertising, fashion, celebrities, television, tattoos, toys, comics, pornography, politics, iPhones, and stuff in general” — is impossible for art history to grasp, even though it is to a great extent the content of contemporary art. But his belief that today’s art “is no longer preoccupied with form” is one that would hardly be accepted by most artists or anyone else who is involved in contemporary art on a daily basis. Pathetically little has improved for menopausal women since Wilson died in 1981. Our fears, degradations, and inequalities are still blamed on us—and are still well-used by corporate pill-pushers. Pharmaceutical industry watchers estimate that by 2022, the HRT market will be worth an estimated $28.4 billion. (By comparison, the annual revenue of one of the top ten pharmaceutical companies in the world, Johnson & Johnson, is $40 billion.)

Pathetically little has improved for menopausal women since Wilson died in 1981. Our fears, degradations, and inequalities are still blamed on us—and are still well-used by corporate pill-pushers. Pharmaceutical industry watchers estimate that by 2022, the HRT market will be worth an estimated $28.4 billion. (By comparison, the annual revenue of one of the top ten pharmaceutical companies in the world, Johnson & Johnson, is $40 billion.) “Mary MacLane is mad,” wrote the New York Herald. “She should be put under medical treatment, and pens and paper kept out of her way until she is restored to reason.” The New York Times urged that she be spanked. Other critics raised the charge of “obscenity.” When the Butte Public Library announced that it would not allow the book on its shelves, the Helena Daily Independent applauded, arguing that if this book “should go in, all the self-respecting books in the library would jump out of the window.”

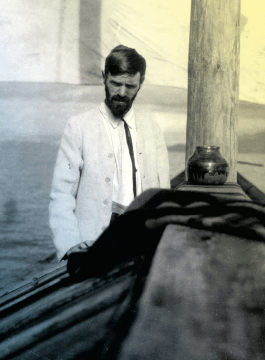

“Mary MacLane is mad,” wrote the New York Herald. “She should be put under medical treatment, and pens and paper kept out of her way until she is restored to reason.” The New York Times urged that she be spanked. Other critics raised the charge of “obscenity.” When the Butte Public Library announced that it would not allow the book on its shelves, the Helena Daily Independent applauded, arguing that if this book “should go in, all the self-respecting books in the library would jump out of the window.” My relationship with D. H. Lawrence began in high school, when I bought a copy of Sons and Lovers more or less at random and proceeded to read it all the way through, by which I mean that my eyes literally traversed every page and recognized that the English language was there recorded in some complexity. But the words, instead of building a reality I could enter and move around in, were like a continually dying fluorescence. I had no idea what was going on. What registered was something like “words, words, flower, sentence, words, coal mining” (like I knew what a coal mine was). As far as I was concerned, Sons and Lovers appeared out of nothing and to nothing it returned. All I knew when I was finished was all I knew before I plucked it, more or less at random, off the shelf: that it was a “classic.”

My relationship with D. H. Lawrence began in high school, when I bought a copy of Sons and Lovers more or less at random and proceeded to read it all the way through, by which I mean that my eyes literally traversed every page and recognized that the English language was there recorded in some complexity. But the words, instead of building a reality I could enter and move around in, were like a continually dying fluorescence. I had no idea what was going on. What registered was something like “words, words, flower, sentence, words, coal mining” (like I knew what a coal mine was). As far as I was concerned, Sons and Lovers appeared out of nothing and to nothing it returned. All I knew when I was finished was all I knew before I plucked it, more or less at random, off the shelf: that it was a “classic.”