Blake Morrison in The Guardian:

Tracking a river through a cedar forest in Ecuador, Robert Macfarlane comes to a 30ft-high waterfall and, below it, a wide pool. It’s irresistible: he plunges in. The water under the falls is turbulent, a thousand little fists punching his shoulders. He’s exhilarated. No one could mistake this for a “dying” river, sluggish or polluted. But that thought sparks others: “Is this thing I’m in really alive? By whose standards? By what proof? As for speaking to or for a river, or comprehending what a river wants – well, where would you even start?”

Tracking a river through a cedar forest in Ecuador, Robert Macfarlane comes to a 30ft-high waterfall and, below it, a wide pool. It’s irresistible: he plunges in. The water under the falls is turbulent, a thousand little fists punching his shoulders. He’s exhilarated. No one could mistake this for a “dying” river, sluggish or polluted. But that thought sparks others: “Is this thing I’m in really alive? By whose standards? By what proof? As for speaking to or for a river, or comprehending what a river wants – well, where would you even start?”

He’s in the right place to be asking. In September 2008, Ecuador, “this small country with a vast moral imagination”, became the first nation in the world to legislate on behalf of water, “since its condition as an essential element for life makes it a necessary aspect for existence of all living beings”. This enshrinement of the Rights of Nature set off similar developments in other countries. In 2017, a law was passed in New Zealand that afforded the Whanganui River protection as a “spiritual and physical entity”. In India, five days later, judges ruled that the Ganges and Yamuna should be recognised as “living entities”. And in 2021, the Mutehekau Shipu (AKA Magpie River) became the first river in Canada to be declared a “legal person [and] living entity”. The Rights of Nature movement has now reached the UK, with Lewes council in East Sussex recognising the rights and legal personhood of the River Ouse.

Macfarlane’s book is timely. Rivers are in crisis worldwide. They have been dammed, poisoned, reduced to servitude, erased from the map.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

In 1995, World Bank Vice President Ismail Serageldin warned that whereas the conflicts of the previous 100 years had been over oil, “the wars of the next century

In 1995, World Bank Vice President Ismail Serageldin warned that whereas the conflicts of the previous 100 years had been over oil, “the wars of the next century  W

W When we think about the forces that shape us, we inevitably turn to parents. The parent-child relationship is the basis of probably half a millennium’s worth of psychoanalytic conversation and intellectual discourse; parenting books are perennial best sellers, with advice that fluctuates as often as the health advice on what to eat or drink and how much. Their whiplashing instructions don’t stop many parents from reading them, and who can blame those mothers and fathers: Children are baffling, variable, not that verbal — and parents also know that if they get it wrong, their kids will blame them for just about everything.

When we think about the forces that shape us, we inevitably turn to parents. The parent-child relationship is the basis of probably half a millennium’s worth of psychoanalytic conversation and intellectual discourse; parenting books are perennial best sellers, with advice that fluctuates as often as the health advice on what to eat or drink and how much. Their whiplashing instructions don’t stop many parents from reading them, and who can blame those mothers and fathers: Children are baffling, variable, not that verbal — and parents also know that if they get it wrong, their kids will blame them for just about everything. There are philosophies of brokenness, which makes sense, given how much broken stuff disrupts the flow of our lives. How should we think about those disruptions? A practitioner of the Japanese ethic of wabi-sabi respects the beauty of brokenness: instead of trying to erase the wear and tear that accrues inevitably with time, she finds ways of acknowledging and celebrating it. In a prototypical example of the philosophy, a teacup that has fallen and shattered is reassembled through the art of kintsugi, in which lacquer, mixed with powdered gold or other metals, is used to fill the cracks; now the fractured, gilded cup tells a story of endurance, authenticity, acceptance, and care amid impermanence. Your favorite jacket, with a mended tear in its lining and the mark of an exploded pen below its pocket, has some wabi-sabi. So does your grandfather’s watch, still functional but with a scratch in its crystal. I like to imagine that the Wabi Sabi Salon, in a town near mine, helps its clients age gracefully. (I’ve never visited.)

There are philosophies of brokenness, which makes sense, given how much broken stuff disrupts the flow of our lives. How should we think about those disruptions? A practitioner of the Japanese ethic of wabi-sabi respects the beauty of brokenness: instead of trying to erase the wear and tear that accrues inevitably with time, she finds ways of acknowledging and celebrating it. In a prototypical example of the philosophy, a teacup that has fallen and shattered is reassembled through the art of kintsugi, in which lacquer, mixed with powdered gold or other metals, is used to fill the cracks; now the fractured, gilded cup tells a story of endurance, authenticity, acceptance, and care amid impermanence. Your favorite jacket, with a mended tear in its lining and the mark of an exploded pen below its pocket, has some wabi-sabi. So does your grandfather’s watch, still functional but with a scratch in its crystal. I like to imagine that the Wabi Sabi Salon, in a town near mine, helps its clients age gracefully. (I’ve never visited.) The videos “starring” the author, who died in 1976, have been made using AI-enhanced technology, licensed images and carefully restored audio recordings.

The videos “starring” the author, who died in 1976, have been made using AI-enhanced technology, licensed images and carefully restored audio recordings. The follicles at the root of each hair contain

The follicles at the root of each hair contain  When the Vietnam War finally ended on April 30, 1975, it left behind a landscape

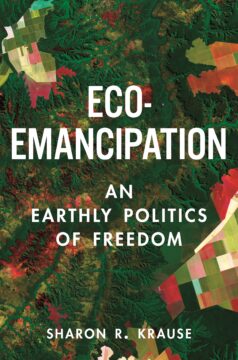

When the Vietnam War finally ended on April 30, 1975, it left behind a landscape  Bringing nonhumans into our democracies may be less radical than it first appears. Nussbaum is quick to clarify that attending to the political voices of animals does not mean giving them a vote in our elections, which “would quickly become absurd.” Her vision is not of beleaguered pets marching down our grand boulevards demanding the vote for every Sparky, Buddy, and Princess. Rather more modestly, she proposes that “duly qualified animal ‘collaborators’ should be charged with making policy on the animals’ behalf, and bringing challenges to unjust arrangements in the courts.” The goal is not to force animals with “little interest in political participation in the human-dominated world” to suddenly take part in “elections, assemblies, and offices.” Nussbaum’s ambition, rather, is for expert guardians to give the “creatures who live in a place […] a say in how they live.”

Bringing nonhumans into our democracies may be less radical than it first appears. Nussbaum is quick to clarify that attending to the political voices of animals does not mean giving them a vote in our elections, which “would quickly become absurd.” Her vision is not of beleaguered pets marching down our grand boulevards demanding the vote for every Sparky, Buddy, and Princess. Rather more modestly, she proposes that “duly qualified animal ‘collaborators’ should be charged with making policy on the animals’ behalf, and bringing challenges to unjust arrangements in the courts.” The goal is not to force animals with “little interest in political participation in the human-dominated world” to suddenly take part in “elections, assemblies, and offices.” Nussbaum’s ambition, rather, is for expert guardians to give the “creatures who live in a place […] a say in how they live.” From a very young age, Murata never thought of her body as her own. “The grownups would always talk about whether Sayaka had childbearing hips,” she recalls. “It was almost like they were keeping an eye on my uterus, which was something that existed not for me, but for them, for the relatives.” No matter how much she tried to resolve the conflict of motherhood in her fiction, she has never escaped “this idea of being expected to reproduce for the good of the village”.

From a very young age, Murata never thought of her body as her own. “The grownups would always talk about whether Sayaka had childbearing hips,” she recalls. “It was almost like they were keeping an eye on my uterus, which was something that existed not for me, but for them, for the relatives.” No matter how much she tried to resolve the conflict of motherhood in her fiction, she has never escaped “this idea of being expected to reproduce for the good of the village”. “Restaurants will break your heart” is something that I often hear myself saying. It has become a mantra. When did I start saying it, I wonder. Maybe it was when I first discovered the criss-crossed lines of affection; falling in a crash-out kind of love with a fellow line cook because he helped me with my mise en place. Maybe it was when my sous-chef first called me mediocre; we all watched slices of chocolate cake I cut pile up in the garbage because of my disappointing quenelles. Maybe it was the first time that I had to fire a kitchen assistant over the phone, hearing him quietly murmur in response, “Okay.” Maybe (definitely) it was the time I got fired—the bad news sandwiched between my manager saying I was “amazing” and also “so great.” Maybe it was the first time I watched a plate of food I made go out and I understood, profoundly, that I would never know who might eat it.

“Restaurants will break your heart” is something that I often hear myself saying. It has become a mantra. When did I start saying it, I wonder. Maybe it was when I first discovered the criss-crossed lines of affection; falling in a crash-out kind of love with a fellow line cook because he helped me with my mise en place. Maybe it was when my sous-chef first called me mediocre; we all watched slices of chocolate cake I cut pile up in the garbage because of my disappointing quenelles. Maybe it was the first time that I had to fire a kitchen assistant over the phone, hearing him quietly murmur in response, “Okay.” Maybe (definitely) it was the time I got fired—the bad news sandwiched between my manager saying I was “amazing” and also “so great.” Maybe it was the first time I watched a plate of food I made go out and I understood, profoundly, that I would never know who might eat it. 1. ESA’s Euclid Telescope Unveils Millions of New Galaxies

1. ESA’s Euclid Telescope Unveils Millions of New Galaxies