Andrew Hui in Aeon:

Andrew Hui in Aeon:

Before the birth of Western philosophy proper, there was the aphorism. In ancient Greece, the short sayings of Anaximander, Xenophanes, Parmenides or Heraclitus constitute the first efforts at speculative thinking, but they are also something to which Plato and Aristotle are hostile. Their enigmatic pronouncements elude discursive analysis. They refuse to be corralled into systematic order. No one would deny that their pithy statements might be wise; but Plato and Aristotle were ambivalent about them. They have no rigour at all – they are just the scattered utterances of clever men.

Here is Plato’s critique of Heraclitus:

If you ask any one of them a question, he will pull out some little enigmatic phrase from his quiver and shoot it off at you; and if you try to make him give an account of what he has said, you will only get hit by another, full of strange turns of language.

For Plato, the Heracliteans’ stratagem of continual evasion is a problem because they constantly produce new aphorisms in order to subvert closure. In this sense, Heraclitus is opposed to Plato in at least two fundamental ways: first, his doctrine of flux is contrary to the theory of Forms; and second, the impression one gets is that his thinking is solitary, monologic, misanthropic, whereas Plato is always social, dialogic, inviting.

More here.

Quinn Slobodian in The Guardian:

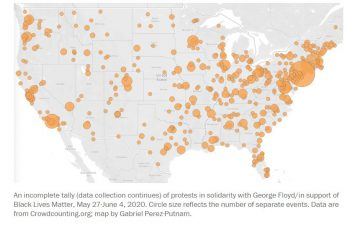

Quinn Slobodian in The Guardian: Lara Putnam, Erica Chenoweth and Jeremy Pressman over at the Monkey Cage:

Lara Putnam, Erica Chenoweth and Jeremy Pressman over at the Monkey Cage: A

A Academic critics of Dryden or Pope were not in the habit, the last time I checked, of interspersing their monographs with reminiscences of sex clubs in Manhattan. An affectionate excursus on that subject in Mark Doty’s What is the Grass announces that this is no ordinary piece of literary criticism. ‘And your very flesh shall be a great poem,’ wrote Doty’s subject, Walt Whitman, who, one suspects, wouldn’t have minded a bit. Perhaps best known for his 1993 collection My Alexandria, prompted by the AIDS pandemic, Doty is one of the most compelling modern singers of ‘the body electric’ and in What is the Grass he has produced an elegant meditation on the great founding father of American poetry. Not only did Whitman’s example fire up the democratic modern lyrics of W C Williams and Allen Ginsberg; it also licensed poets to place themselves centre stage in their prose, from Adrienne Rich in What is Found There to Susan Howe in her prose-poetry hybrids. It is a licence that Doty seizes on greedily.

Academic critics of Dryden or Pope were not in the habit, the last time I checked, of interspersing their monographs with reminiscences of sex clubs in Manhattan. An affectionate excursus on that subject in Mark Doty’s What is the Grass announces that this is no ordinary piece of literary criticism. ‘And your very flesh shall be a great poem,’ wrote Doty’s subject, Walt Whitman, who, one suspects, wouldn’t have minded a bit. Perhaps best known for his 1993 collection My Alexandria, prompted by the AIDS pandemic, Doty is one of the most compelling modern singers of ‘the body electric’ and in What is the Grass he has produced an elegant meditation on the great founding father of American poetry. Not only did Whitman’s example fire up the democratic modern lyrics of W C Williams and Allen Ginsberg; it also licensed poets to place themselves centre stage in their prose, from Adrienne Rich in What is Found There to Susan Howe in her prose-poetry hybrids. It is a licence that Doty seizes on greedily. Before Italy became a nation, it was made up of a collection of city-states governed by un’autorità superior, in the form of a powerful noble family or a bishop. Siena was an exception in that it favoured civic rule. This partly accounts for the unique character of its art. It produced Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s The Allegory of Good and Bad Government, a series of frescos housed in the Palazzo Pubblico, the civic heart of the city. It is one of the earliest and most significant secular paintings we have. If civic rule were a church, this would be its altarpiece. Siena also imbued its artists with a rare and humanist curiosity that, even in their depictions of religious scenes, involved them in meditations on human psychology and ideas.

Before Italy became a nation, it was made up of a collection of city-states governed by un’autorità superior, in the form of a powerful noble family or a bishop. Siena was an exception in that it favoured civic rule. This partly accounts for the unique character of its art. It produced Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s The Allegory of Good and Bad Government, a series of frescos housed in the Palazzo Pubblico, the civic heart of the city. It is one of the earliest and most significant secular paintings we have. If civic rule were a church, this would be its altarpiece. Siena also imbued its artists with a rare and humanist curiosity that, even in their depictions of religious scenes, involved them in meditations on human psychology and ideas.

In 1916, the 26-year-old Agatha Christie finished writing her first detective novel at Dartmoor, a quiet upland in Devon, UK, known for its beautiful granite hilltops. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle had published The Hound of the Baskervilles, in 1902, which would become one of the most widely read Sherlock Holmes adventures—and the story was set in this same corner of the world, Dartmoor.

In 1916, the 26-year-old Agatha Christie finished writing her first detective novel at Dartmoor, a quiet upland in Devon, UK, known for its beautiful granite hilltops. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle had published The Hound of the Baskervilles, in 1902, which would become one of the most widely read Sherlock Holmes adventures—and the story was set in this same corner of the world, Dartmoor. The

The  As it turns out, humans are wired to worry. Our brains are continually imagining futures that will meet our needs and things that could stand in the way of them. And sometimes any of those needs may be in conflict with each other.

As it turns out, humans are wired to worry. Our brains are continually imagining futures that will meet our needs and things that could stand in the way of them. And sometimes any of those needs may be in conflict with each other. In the opening lines of Cold Warriors, Duncan White notes that “between February and May 1955, a group covertly funded by the Central Intelligence Agency launched a secret weapon into Communist territory”: balloons carrying copies of George Orwell’s

In the opening lines of Cold Warriors, Duncan White notes that “between February and May 1955, a group covertly funded by the Central Intelligence Agency launched a secret weapon into Communist territory”: balloons carrying copies of George Orwell’s  In the early nineteen-hundreds, the American writer O. Henry coined the term “banana republic” in a series of

In the early nineteen-hundreds, the American writer O. Henry coined the term “banana republic” in a series of  The idea for publishing a novel posthumously came to Kingston after learning of Mark Twain’s autobiography, which wasn’t released in uncensored form until 2010, a hundred years after his death. If Kingston knew that she wouldn’t have to answer for her work, perhaps she would be able to write more freely. At first, her notes represented an attempt to capture each day’s “intensity,” she said. In time, she realized that she had written about twelve hundred single-spaced pages. She continued writing. She told her agent, Sandy Dijkstra, that the book would remain unpublished for a hundred years. “I was stunned, shocked, and more,” Dijkstra said in an e-mail, “and told her that I could not promise to be a living and functioning agent a century from now.” Kingston has not shown her any of it. “Maybe you can persuade Maxine to show it to us much sooner,” she said. “Magical thinking works on the page, but not so well in real life.”

The idea for publishing a novel posthumously came to Kingston after learning of Mark Twain’s autobiography, which wasn’t released in uncensored form until 2010, a hundred years after his death. If Kingston knew that she wouldn’t have to answer for her work, perhaps she would be able to write more freely. At first, her notes represented an attempt to capture each day’s “intensity,” she said. In time, she realized that she had written about twelve hundred single-spaced pages. She continued writing. She told her agent, Sandy Dijkstra, that the book would remain unpublished for a hundred years. “I was stunned, shocked, and more,” Dijkstra said in an e-mail, “and told her that I could not promise to be a living and functioning agent a century from now.” Kingston has not shown her any of it. “Maybe you can persuade Maxine to show it to us much sooner,” she said. “Magical thinking works on the page, but not so well in real life.” From time to time, Andy Warhol entertained the wish to host a television show called Nothing Special, and to operate a chain of cafeterias for solitary diners, the Andy-Mat. A social oddity since his Dickensian childhood, Warhol retained the imprint of not-having and not-belonging into adulthood, acquiring vivid people he didn’t much care about and pricey objects he never looked at. To a society poised to reject him, he presented a façade of detachment from other people’s lives, even from his own: in an interview with Alfred Hitchcock, he said that getting shot had been “like watching TV.”

From time to time, Andy Warhol entertained the wish to host a television show called Nothing Special, and to operate a chain of cafeterias for solitary diners, the Andy-Mat. A social oddity since his Dickensian childhood, Warhol retained the imprint of not-having and not-belonging into adulthood, acquiring vivid people he didn’t much care about and pricey objects he never looked at. To a society poised to reject him, he presented a façade of detachment from other people’s lives, even from his own: in an interview with Alfred Hitchcock, he said that getting shot had been “like watching TV.” In January,

In January,