Jeffrey S. Flier in Quillette:

There has been consensus in the scientific community that, notwithstanding the partial effectiveness of lockdowns, other non-pharmacologic interventions, and potential therapeutics, the development and production of a safe and effective vaccine would eventually be necessary to fully control this pandemic. But it is important to remember that some viruses resist vaccine treatment (as so far has been the case with HIV). In other cases, vaccines are developed, but only after many years of research, testing, and regulatory protocols. Attempts to produce vaccines for the two other known human coronavirus diseases—SARS, which was identified in 2002, and MERS, in 2012—were unsuccessful. So optimism has been appropriately muted in the case of COVID-19. And it’s in this context that these preliminary results are so remarkable.

More here.

Pakistan was created in 1947 as a homeland for the Muslims of Hindu-majority India—“carved from the flanks of British India,” as Mr. Walsh puts it. Its “Great Leader” (“Quaid-e-Azam” in Urdu) was Muhammad Ali Jinnah, an unlikely agitator for a confessional Muslim state. A worldly lawyer who drank alcohol and married outside his faith, he was, Mr. Walsh tells us, “purposefully vague about his beliefs” for much of his life. In a poignant passage, Mr. Walsh parses a photograph of Jinnah taken in September 1947, a month after Pakistan was born: In it, he wears “the gaze of a man who gambled at the table of history, won big—and now wonders whether he won more than he bargained for.”

Pakistan was created in 1947 as a homeland for the Muslims of Hindu-majority India—“carved from the flanks of British India,” as Mr. Walsh puts it. Its “Great Leader” (“Quaid-e-Azam” in Urdu) was Muhammad Ali Jinnah, an unlikely agitator for a confessional Muslim state. A worldly lawyer who drank alcohol and married outside his faith, he was, Mr. Walsh tells us, “purposefully vague about his beliefs” for much of his life. In a poignant passage, Mr. Walsh parses a photograph of Jinnah taken in September 1947, a month after Pakistan was born: In it, he wears “the gaze of a man who gambled at the table of history, won big—and now wonders whether he won more than he bargained for.” There she stands, the fortysomething Susan Sontag, at a rock ‘n’ roll show in a packed New York club, encircled by sweaty kids. “Being the oldest person in a room did not make her self-conscious,” writes Sigrid Nunez in her memoir Sempre Susan. “The idea that she could ever be out of place anywhere because of her age was beyond her—like the idea that she could ever be de trop.” Sontag gave herself a regal, Oscar-Wilde-like permission to be at the center of things. That could be charming, much of the time. Other traits were less appealing. Sontag used to forbid her son David to look out of the window during train trips because, after all, there was nothing interesting about nature. Read a book instead, or, better, talk to me! was her message.

There she stands, the fortysomething Susan Sontag, at a rock ‘n’ roll show in a packed New York club, encircled by sweaty kids. “Being the oldest person in a room did not make her self-conscious,” writes Sigrid Nunez in her memoir Sempre Susan. “The idea that she could ever be out of place anywhere because of her age was beyond her—like the idea that she could ever be de trop.” Sontag gave herself a regal, Oscar-Wilde-like permission to be at the center of things. That could be charming, much of the time. Other traits were less appealing. Sontag used to forbid her son David to look out of the window during train trips because, after all, there was nothing interesting about nature. Read a book instead, or, better, talk to me! was her message. But, more importantly: the artist does not in fact require too detailed a study of his predecessors. It was only by fencing myself off, and not knowing most of what was written before me, that I’ve been able to fulfill my great task: otherwise you wear out and dissolve in it and accomplish nothing. If I’d read The Magic Mountain (and I still haven’t), it might somehow have impeded my writing of Cancer Ward. I was saved by the fact that my self-propelled development didn’t get distorted. I have always been hungry for reading, for knowledge—but in my school years in the provinces, when I was freer, I didn’t have that sort of guidance or access to that sort of library. And starting from my student years, my life was swallowed up by mathematics. I’d just set up a fragile connection with the Moscow Institute of Philosophy, Literature and History when the war came, then prison, the camps, internal exile, and teaching—still mathematics, but physics too (preparing experiments for demonstration in class, which I found very difficult). And years and years of conspiring under pressure and racing, underground, to complete my books, for the sake of all those who’d died without a chance to speak. In my life I’ve had to gain a thorough grounding in artillery, oncology, the First World War, and then prerevolutionary Russia too, which by then was so impossible to imagine.

But, more importantly: the artist does not in fact require too detailed a study of his predecessors. It was only by fencing myself off, and not knowing most of what was written before me, that I’ve been able to fulfill my great task: otherwise you wear out and dissolve in it and accomplish nothing. If I’d read The Magic Mountain (and I still haven’t), it might somehow have impeded my writing of Cancer Ward. I was saved by the fact that my self-propelled development didn’t get distorted. I have always been hungry for reading, for knowledge—but in my school years in the provinces, when I was freer, I didn’t have that sort of guidance or access to that sort of library. And starting from my student years, my life was swallowed up by mathematics. I’d just set up a fragile connection with the Moscow Institute of Philosophy, Literature and History when the war came, then prison, the camps, internal exile, and teaching—still mathematics, but physics too (preparing experiments for demonstration in class, which I found very difficult). And years and years of conspiring under pressure and racing, underground, to complete my books, for the sake of all those who’d died without a chance to speak. In my life I’ve had to gain a thorough grounding in artillery, oncology, the First World War, and then prerevolutionary Russia too, which by then was so impossible to imagine. Barack Obama is as fine a writer as they come. It is not merely that this book avoids being ponderous, as might be expected, even forgiven, of a hefty memoir, but that it is nearly always pleasurable to read, sentence by sentence, the prose gorgeous in places, the detail granular and vivid. From Southeast Asia to a forgotten school in South Carolina, he evokes the sense of place with a light but sure hand. This is the first of two volumes, and it starts early in his life, charting his initial political campaigns, and ends with a meeting in Kentucky where he is introduced to the SEAL team involved in the Abbottabad raid that killed Osama bin Laden.

Barack Obama is as fine a writer as they come. It is not merely that this book avoids being ponderous, as might be expected, even forgiven, of a hefty memoir, but that it is nearly always pleasurable to read, sentence by sentence, the prose gorgeous in places, the detail granular and vivid. From Southeast Asia to a forgotten school in South Carolina, he evokes the sense of place with a light but sure hand. This is the first of two volumes, and it starts early in his life, charting his initial political campaigns, and ends with a meeting in Kentucky where he is introduced to the SEAL team involved in the Abbottabad raid that killed Osama bin Laden. We live in a golden age of science writing, where weighty subjects such as quantum mechanics, genetics and cell theory are routinely rendered intelligible to mass audiences. Nonetheless, it remains rare for even the most talented science writers to fuse their work with a deep knowledge of the arts. One such rarity is the Italian theoretical physicist Carlo Rovelli who, like some intellectual throwback to antiquity, treats the sciences and the humanities as complementary areas of knowledge and is a subtle interpreter of both. His best-known work is

We live in a golden age of science writing, where weighty subjects such as quantum mechanics, genetics and cell theory are routinely rendered intelligible to mass audiences. Nonetheless, it remains rare for even the most talented science writers to fuse their work with a deep knowledge of the arts. One such rarity is the Italian theoretical physicist Carlo Rovelli who, like some intellectual throwback to antiquity, treats the sciences and the humanities as complementary areas of knowledge and is a subtle interpreter of both. His best-known work is  ON JULY 21, 2016, the Republican National Convention was in full swing and delegates in ruddy Americana and cowboy attire packed the Cleveland’s Quicken Loans Arena. Although it’s hard for most of us to recall, this was a time where even staunch Republicans were doubting Trump’s ascendency to the United States’s highest office. I was there, and remember it fondly, and was intrigued as to why those who did want Trump were willing to vote for a man who had called Mexicans rapists and had made fun of a handicapped New York Times journalist. A 52-year-old delegate from Vermont stressed the usual three prongs: the border, anti-terrorism, the military. Trump’s insensitivity mattered not. “To me,” the delegate said, “if you’re not safe, then you’ve got nothing.”

ON JULY 21, 2016, the Republican National Convention was in full swing and delegates in ruddy Americana and cowboy attire packed the Cleveland’s Quicken Loans Arena. Although it’s hard for most of us to recall, this was a time where even staunch Republicans were doubting Trump’s ascendency to the United States’s highest office. I was there, and remember it fondly, and was intrigued as to why those who did want Trump were willing to vote for a man who had called Mexicans rapists and had made fun of a handicapped New York Times journalist. A 52-year-old delegate from Vermont stressed the usual three prongs: the border, anti-terrorism, the military. Trump’s insensitivity mattered not. “To me,” the delegate said, “if you’re not safe, then you’ve got nothing.” In a series of breakthrough papers, theoretical physicists have come tantalizingly close to resolving the

In a series of breakthrough papers, theoretical physicists have come tantalizingly close to resolving the  Five years ago, American journalists called me following the terrorist attack that took the lives of my former colleagues and friends at Charlie Hebdo. They all thought that we were going to elect Marine Le Pen. I tried to explain to them that it’s precisely because there is a leftist movement associated with Charlie—both anti-racist and secular, a left that remains lucid about the dangers of extremism—that we had a chance to avoid that fate. But my explanations were in vain.

Five years ago, American journalists called me following the terrorist attack that took the lives of my former colleagues and friends at Charlie Hebdo. They all thought that we were going to elect Marine Le Pen. I tried to explain to them that it’s precisely because there is a leftist movement associated with Charlie—both anti-racist and secular, a left that remains lucid about the dangers of extremism—that we had a chance to avoid that fate. But my explanations were in vain. The evolutionary explanation for human connection to nature is a colossal safari through the African savanna, where our ancestors fought, fed, and frolicked for millions of years. The biologist E.O. Wilson speculated on this story in Biophilia, a slim volume on human attraction to nature. Wilson defined biophilia as an “innate tendency to focus on life and lifelike processes.” He argued that if other animals are adapted to their environments and are best-suited to the environments in which they evolved—for example, a thick white coat serves the polar bear well in its native cold and snowy Arctic—then is it possible that humans too, despite our ability to live anywhere on this planet, are best adapted to the particular environment in which we evolved?

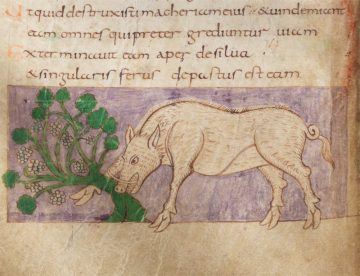

The evolutionary explanation for human connection to nature is a colossal safari through the African savanna, where our ancestors fought, fed, and frolicked for millions of years. The biologist E.O. Wilson speculated on this story in Biophilia, a slim volume on human attraction to nature. Wilson defined biophilia as an “innate tendency to focus on life and lifelike processes.” He argued that if other animals are adapted to their environments and are best-suited to the environments in which they evolved—for example, a thick white coat serves the polar bear well in its native cold and snowy Arctic—then is it possible that humans too, despite our ability to live anywhere on this planet, are best adapted to the particular environment in which we evolved? These are ancient texts, but the pig’s characterization as a ravenous and dirty animal has transcended particular historical moments. Christians in early medieval Europe made the same associations, and so do we. More than one historian has pointed this out over the years, partly with the goal of rehabilitating the animals’ reputation. But this flat stereotype, this singular beast, was not the only profile a pig could have, even in the past: “premodern” views were subtler than the shorthand symbolism suggests. In late antiquity and the early Middle Ages, farmers, policy makers, and philosophers were perfectly capable of holding multiple views of pigs simultaneously, of playing into a familiar caricature but also of honing in on the complexities of the species. They saw that pigs were not merely commodities that provided humans with meat or symbols that worked as handy metaphors. They were also creatures that were capable of adapting to and altering their environments, including the human environments that only partially constrained them. Pigs were difficult to fully domesticate, both physically and conceptually. They called attention to themselves and required some engagement with their complex lives.

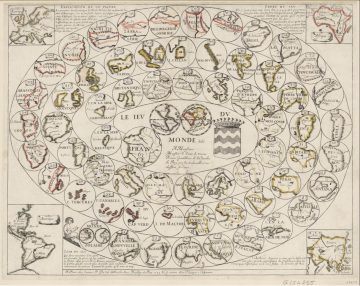

These are ancient texts, but the pig’s characterization as a ravenous and dirty animal has transcended particular historical moments. Christians in early medieval Europe made the same associations, and so do we. More than one historian has pointed this out over the years, partly with the goal of rehabilitating the animals’ reputation. But this flat stereotype, this singular beast, was not the only profile a pig could have, even in the past: “premodern” views were subtler than the shorthand symbolism suggests. In late antiquity and the early Middle Ages, farmers, policy makers, and philosophers were perfectly capable of holding multiple views of pigs simultaneously, of playing into a familiar caricature but also of honing in on the complexities of the species. They saw that pigs were not merely commodities that provided humans with meat or symbols that worked as handy metaphors. They were also creatures that were capable of adapting to and altering their environments, including the human environments that only partially constrained them. Pigs were difficult to fully domesticate, both physically and conceptually. They called attention to themselves and required some engagement with their complex lives. In 1795, Henry Carington Bowles released Bowles’s European Geographical Amusement, or Game of Geography, the latest in his family’s board game series. Allegedly based on a 1749 travelogue, “the Grand Tour of Europe, by Dr. Nugent,” it combined learned pretensions with simple rules. “Having agreed to make an elegant and instructive TOUR of EUROPE,” players took turns rolling an eight-sided “Totum” and moving their “Pillars” through the appropriate number of cities. Whoever returned to London first was “entitled to the applause of the company and honor of being esteemed the best instructed and speediest traveler”: an enviable but deceptive accolade. In fact, erudition and swiftness were inversely correlated in Bowles’s game; being “instructed” required that your Pillar be delayed.

In 1795, Henry Carington Bowles released Bowles’s European Geographical Amusement, or Game of Geography, the latest in his family’s board game series. Allegedly based on a 1749 travelogue, “the Grand Tour of Europe, by Dr. Nugent,” it combined learned pretensions with simple rules. “Having agreed to make an elegant and instructive TOUR of EUROPE,” players took turns rolling an eight-sided “Totum” and moving their “Pillars” through the appropriate number of cities. Whoever returned to London first was “entitled to the applause of the company and honor of being esteemed the best instructed and speediest traveler”: an enviable but deceptive accolade. In fact, erudition and swiftness were inversely correlated in Bowles’s game; being “instructed” required that your Pillar be delayed. At the end of 1525, Zahiru’d-din Muhammad Babur, a Timurid poet-prince from Farghana in Central Asia, descended the Khyber Pass with a small army of hand-picked followers; with him he brought some of the first modern muskets and cannons seen in India. With these he defeated the Delhi Sultan, Ibrahim Lodhi, and established his garden-capital at Agra.

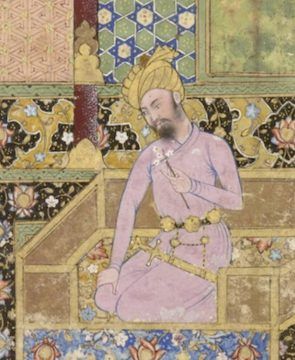

At the end of 1525, Zahiru’d-din Muhammad Babur, a Timurid poet-prince from Farghana in Central Asia, descended the Khyber Pass with a small army of hand-picked followers; with him he brought some of the first modern muskets and cannons seen in India. With these he defeated the Delhi Sultan, Ibrahim Lodhi, and established his garden-capital at Agra.