Tim Dee in The Guardian:

How does your garden grow? Meddling with the soil and what might sprout from it, we hope for a piece of paradise on Earth – in Xanadu, but also in Sidcup and Roath and Lossiemouth. It is necessary to cultivate your garden, Voltaire said, meaning pretty much whatever you’d like. All gardens are plots. They are projects for their gardeners and end up being projections of them too. Can Marc Hamer’s cultivation of someone else’s garden enlighten us on how to live well today? Green thoughts, Andrew Marvell said, come from any green shade, but Hamer doesn’t stop there. His first book, A Life in Nature or How to Catch a Mole, also traded in wisdom (and its corrections) got from nature. He is adamant that his gardening the 12 acres belonging to an elderly widow, Miss Cashmere, is “work”. But through his salaried labour comes an almanac of meditations or parables or thoughts-for-the-day, got from dandelions and roses, lawnmowers and secateurs, dead-heading and mulching.

How does your garden grow? Meddling with the soil and what might sprout from it, we hope for a piece of paradise on Earth – in Xanadu, but also in Sidcup and Roath and Lossiemouth. It is necessary to cultivate your garden, Voltaire said, meaning pretty much whatever you’d like. All gardens are plots. They are projects for their gardeners and end up being projections of them too. Can Marc Hamer’s cultivation of someone else’s garden enlighten us on how to live well today? Green thoughts, Andrew Marvell said, come from any green shade, but Hamer doesn’t stop there. His first book, A Life in Nature or How to Catch a Mole, also traded in wisdom (and its corrections) got from nature. He is adamant that his gardening the 12 acres belonging to an elderly widow, Miss Cashmere, is “work”. But through his salaried labour comes an almanac of meditations or parables or thoughts-for-the-day, got from dandelions and roses, lawnmowers and secateurs, dead-heading and mulching.

Hamer writes his plants well but finds knowledge awkward. His flower biographies (a striking number are poisonous) include the species’ scientific name, but he resists any other book learning and repeatedly says he knows very little – “I like my head to be clean and empty” – as if it were a spiritual goal to be de-cluttered of facts. He regards knowing the difference between a hawk and a falcon as clouding an encounter with any such bird: “Nature doesn’t waste its time on that.” This is strange (and wrong) – it must limit the breadth of what is written – but it suits Hamer who sees himself more green-man than professional plantsman, someone “horned” and “hooved” in the university of muddy life. It also puts him in the company of farm-labourer John Clare, who said he found his poems in the fields. A story at the heart of Hamer’s book turns on the poet.

More here.

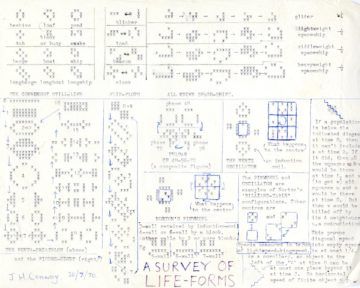

In March of 1970, Martin Gardner opened a letter jammed with ideas for his Mathematical Games column in Scientific American. Sent by John Horton Conway, then a mathematician at the University of Cambridge, the letter ran 12 pages, typed hunt-and-peck style. Page 9 began with the heading “The game of life.” It described an elegant mathematical model of computation — a cellular automaton, a little machine, of sorts, with groups of cells that evolve from iteration to iteration, as a clock advances from one second to the next. Dr. Conway, who

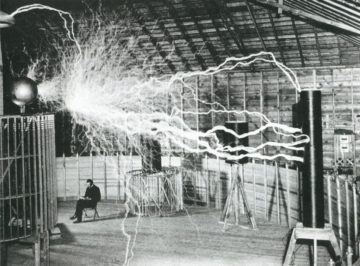

In March of 1970, Martin Gardner opened a letter jammed with ideas for his Mathematical Games column in Scientific American. Sent by John Horton Conway, then a mathematician at the University of Cambridge, the letter ran 12 pages, typed hunt-and-peck style. Page 9 began with the heading “The game of life.” It described an elegant mathematical model of computation — a cellular automaton, a little machine, of sorts, with groups of cells that evolve from iteration to iteration, as a clock advances from one second to the next. Dr. Conway, who  The strangeness of electricity seemed to be that it was at once “so moveable and incapable of rest” and yet also capable of being arrested if deprived of a suitable conductor, for example, by the air. This latter had been demonstrated most dramatically by the experiments of Stephen Gray in the early 1700s, who had electrified charity boys, an ample supply of which was furnished by Charterhouse where he was resident, hung from silken cords in mid-air. The sense that electricity belongs naturally to “the more hidden properties of the air” is borne out by the fact that so many demonstrations and depictions showed electrified subjects who were themselves suspended in midair (even though the reason for this is actually to use the air as insulation). Charles Burney, the father of the novelist Fanny, recorded in 1775 his terror at being caught in a thunderstorm in Bavaria, and his wish for a bed off the ground, so he might sleep in safety “suspended by silk cords in the middle of a large room.”

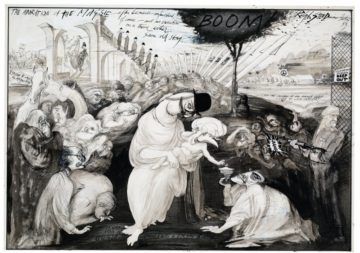

The strangeness of electricity seemed to be that it was at once “so moveable and incapable of rest” and yet also capable of being arrested if deprived of a suitable conductor, for example, by the air. This latter had been demonstrated most dramatically by the experiments of Stephen Gray in the early 1700s, who had electrified charity boys, an ample supply of which was furnished by Charterhouse where he was resident, hung from silken cords in mid-air. The sense that electricity belongs naturally to “the more hidden properties of the air” is borne out by the fact that so many demonstrations and depictions showed electrified subjects who were themselves suspended in midair (even though the reason for this is actually to use the air as insulation). Charles Burney, the father of the novelist Fanny, recorded in 1775 his terror at being caught in a thunderstorm in Bavaria, and his wish for a bed off the ground, so he might sleep in safety “suspended by silk cords in the middle of a large room.” Ralph Steadman was born in Liverpool in 1936, and during the Second World War his family relocated to North Wales. Having honed his technical drawing skills during military service, he moved to London in the 1950s and started work as a cartoonist. Over the course of his 60-year career, Steadman has illustrated classics such as Animal Farm, drawn album covers for bands including the Who, and produced scathing political caricatures for publications on both sides of the Atlantic (he has been contributing to the New Statesman since 1976). He is perhaps best known for his collaborations with the American gonzo journalist Hunter S Thompson, particularly for Thompson’s 1971 novel Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. Steadman’s provocative, ink-splattered images – some of which, taken from a major new book, are reprinted here – are informed by his philosophy: “There is no such thing as a mistake. A mistake is an opportunity to do something else.”

Ralph Steadman was born in Liverpool in 1936, and during the Second World War his family relocated to North Wales. Having honed his technical drawing skills during military service, he moved to London in the 1950s and started work as a cartoonist. Over the course of his 60-year career, Steadman has illustrated classics such as Animal Farm, drawn album covers for bands including the Who, and produced scathing political caricatures for publications on both sides of the Atlantic (he has been contributing to the New Statesman since 1976). He is perhaps best known for his collaborations with the American gonzo journalist Hunter S Thompson, particularly for Thompson’s 1971 novel Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. Steadman’s provocative, ink-splattered images – some of which, taken from a major new book, are reprinted here – are informed by his philosophy: “There is no such thing as a mistake. A mistake is an opportunity to do something else.” Anyone who has been a teenager or dressed a 4-year-old knows that what we wear can be a source of intense conflict. Clothing is more than essential protection against the elements. It helps define who we are—to the world and to ourselves. And it is an everyday source of aesthetic pleasure. Clothing is a form of self-expression.

Anyone who has been a teenager or dressed a 4-year-old knows that what we wear can be a source of intense conflict. Clothing is more than essential protection against the elements. It helps define who we are—to the world and to ourselves. And it is an everyday source of aesthetic pleasure. Clothing is a form of self-expression. When the Khoisan hunter-gatherers of sub-Saharan Africa gazed upon the meandering trail of stars and dust that split the night sky, they saw the embers of a campfire. Polynesian sailors perceived a cloud-eating shark. The ancient Greeks saw a stream of milk, gala, which would eventually give rise to the modern term “galaxy.”

When the Khoisan hunter-gatherers of sub-Saharan Africa gazed upon the meandering trail of stars and dust that split the night sky, they saw the embers of a campfire. Polynesian sailors perceived a cloud-eating shark. The ancient Greeks saw a stream of milk, gala, which would eventually give rise to the modern term “galaxy.” Archaeologists in Pompeii, the city buried in a volcanic eruption in 79 AD, have made the extraordinary find of a frescoed hot food and drinks shop that served up the ancient equivalent of street food to Roman passersby.

Archaeologists in Pompeii, the city buried in a volcanic eruption in 79 AD, have made the extraordinary find of a frescoed hot food and drinks shop that served up the ancient equivalent of street food to Roman passersby. When she began writing “

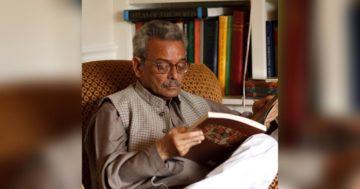

When she began writing “ This annus horribilis is not over yet, and it has now taken away from us the greatest doyen and scholar of Urdu literature the world knew over the recent decades, Shamsur Rahman Faruqi. He died peacefully at his home, surrounded by his family and his favourite dogs, having recovered earlier this month from Covid-19. I had the honour and pleasure to visit him in his study in January this year, which isn’t anything less than a library. It is hard to imagine all those books siting there without their avid reader. Ghalib’s often quoted verse “aisā kahan se laun ki tujh saa kahen jise” – “where do I find another who may be like you?” – doesn’t seem to hold truer than in this moment of the greatest loss for Urdu culture.

This annus horribilis is not over yet, and it has now taken away from us the greatest doyen and scholar of Urdu literature the world knew over the recent decades, Shamsur Rahman Faruqi. He died peacefully at his home, surrounded by his family and his favourite dogs, having recovered earlier this month from Covid-19. I had the honour and pleasure to visit him in his study in January this year, which isn’t anything less than a library. It is hard to imagine all those books siting there without their avid reader. Ghalib’s often quoted verse “aisā kahan se laun ki tujh saa kahen jise” – “where do I find another who may be like you?” – doesn’t seem to hold truer than in this moment of the greatest loss for Urdu culture. Bill McKibben in The New Yorker:

Bill McKibben in The New Yorker: Mingtang Liu and Kellee S. Tsai in the Marxist Sociology blog:

Mingtang Liu and Kellee S. Tsai in the Marxist Sociology blog: Agnes Callard in Boston Review:

Agnes Callard in Boston Review:

Peter Hudis in Jacobin:

Peter Hudis in Jacobin: When Philippa Perry finished, after several years of writing and a lifetime of research, the first draft of her book about improving relationships between parents and children, she sent it to her editor – and their relationship promptly collapsed.

When Philippa Perry finished, after several years of writing and a lifetime of research, the first draft of her book about improving relationships between parents and children, she sent it to her editor – and their relationship promptly collapsed.  The question has confounded many: How does Pakistan stay alive?

The question has confounded many: How does Pakistan stay alive?