From PBS:

In an effort to honor this expansive and growing history, Black History Month was established by way of a weekly celebration in February known as “Negro History Week” by historian Carter G. Woodson. But just as Black history is more than a month, so too are the numerous events and figures that are often overlooked during it. What follows is a list of some of those “lesser known” moments and facts in Black history.

In an effort to honor this expansive and growing history, Black History Month was established by way of a weekly celebration in February known as “Negro History Week” by historian Carter G. Woodson. But just as Black history is more than a month, so too are the numerous events and figures that are often overlooked during it. What follows is a list of some of those “lesser known” moments and facts in Black history.

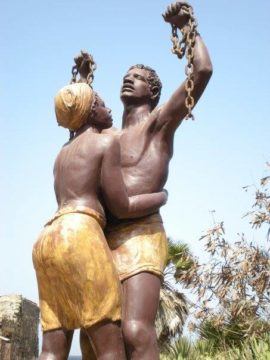

Of the 12.5 million Africans shipped to the New World during the Transatlantic Slave Trade, fewer than 388,000 arrived in the United States.

In the late 15th century, the advancement of seafaring technologies created a new Atlantic that would change the world forever. As ships began connecting West Africa with Europe and the Americas, new fortunes were sought and native populations were decimated. With the native labor force dwindling and demand for plantation and mining labor growing, the transatlantic slave trade began. The Transatlantic Slave Trade was underway from 1500-1866, shipping more than 12 million African slaves across the world. Of those slaves, only 10.7 million survived the dreaded Middle Passage. Over 400 years, the majority of slaves (4.9 million) found their way to Brazil where they suffered incredibly high mortality rates due to terrible working conditions. Brazil was also the last country to ban slavery in 1888. By the time the United States became involved in the slave trade, it had been underway for two hundred years. The majority of its 388,000 slaves arrived between 1700 and 1866, representing a much smaller percentage than most Americans realize.

More here. (Throughout February, at least one post will be dedicated to honoring Black History Month. The theme this year is: The Family)

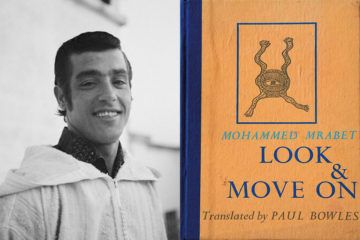

Like many readers, I suspect, I first came across the name Mohammed Mrabet in relation to Paul Bowles. Throughout the sixties, seventies, and eighties, everyone from Life magazine to Rolling Stone sent writers and photographers to Tangier—where Bowles had been living since 1947—to interview the famous American expat, author of the cult classic The Sheltering Sky. “If Paul Bowles, now seventy-four, were Japanese, he would probably be designated a Living National Treasure; if he were French, he would no doubt be besieged by television crews from the literary talk show Apostrophes,” wrote Jay McInerney in one such piece for Vanity Fair in 1985. “Given that he is American, we might expect him to be a part of the university curriculum, but his name rarely appears in a course syllabus. Perhaps because he is not representative of a particular period or school of writing, he remains something of a trade secret among writers.” This wasn’t to say that Bowles was reclusive. In fact, he kept open house for one and all, whether they be curious tourists, his famous friends—Tennessee Williams, William S. Burroughs, and Allen Ginsberg among them—or the crowd of Moroccan storytellers and artists he’d befriended over the years. And of these, one man in particular stands out: Mohammed Mrabet.

Like many readers, I suspect, I first came across the name Mohammed Mrabet in relation to Paul Bowles. Throughout the sixties, seventies, and eighties, everyone from Life magazine to Rolling Stone sent writers and photographers to Tangier—where Bowles had been living since 1947—to interview the famous American expat, author of the cult classic The Sheltering Sky. “If Paul Bowles, now seventy-four, were Japanese, he would probably be designated a Living National Treasure; if he were French, he would no doubt be besieged by television crews from the literary talk show Apostrophes,” wrote Jay McInerney in one such piece for Vanity Fair in 1985. “Given that he is American, we might expect him to be a part of the university curriculum, but his name rarely appears in a course syllabus. Perhaps because he is not representative of a particular period or school of writing, he remains something of a trade secret among writers.” This wasn’t to say that Bowles was reclusive. In fact, he kept open house for one and all, whether they be curious tourists, his famous friends—Tennessee Williams, William S. Burroughs, and Allen Ginsberg among them—or the crowd of Moroccan storytellers and artists he’d befriended over the years. And of these, one man in particular stands out: Mohammed Mrabet. When the New York Times Magazine ran

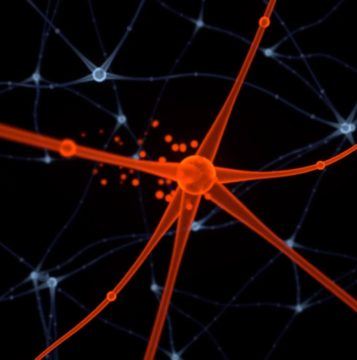

When the New York Times Magazine ran  In 2007, some of the leading thinkers behind deep neural networks organized an unofficial “satellite” meeting at the margins of a prestigious annual conference on artificial intelligence. The conference had rejected their request for an official workshop; deep neural nets were still a few years away from taking over AI. The bootleg meeting’s final speaker was

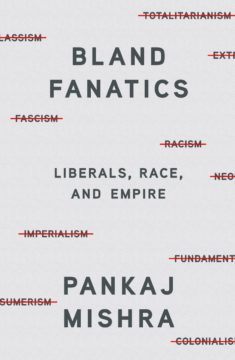

In 2007, some of the leading thinkers behind deep neural networks organized an unofficial “satellite” meeting at the margins of a prestigious annual conference on artificial intelligence. The conference had rejected their request for an official workshop; deep neural nets were still a few years away from taking over AI. The bootleg meeting’s final speaker was  For nearly three decades, Mishra has skewered the pieties of politicians and intellectuals in the Anglophone world (including India, which boasts more English speakers than the United Kingdom), while also bringing his spirited attention to the histories and imaginations of people outside circles of wealth and power. The scales first fell from his eyes during his travels and reporting in Kashmir in the late 1990s and early 2000s. In the disputed Indian-administered territory, he saw firsthand the collision between India’s pluralist liberal democracy—its avowed commitment to democratic norms, individual rights, and multiculturalism—and the reality of military occupation. Indian apologia for abuses in Kashmir, he writes, “prepared me for the spectacle of a liberal intelligentsia cheerleading the war for ‘human rights’ in Iraq, with the kind of humanitarian rhetoric about freedom, democracy and progress that was originally heard from European imperialists in the nineteenth century.” The remit of Mishra’s work has grown steadily wider over the decades, from an early focus on the dreams and catastrophes of small-town India, to a thoughtful exploration of colonial-era Asian intellectual history in the excellent

For nearly three decades, Mishra has skewered the pieties of politicians and intellectuals in the Anglophone world (including India, which boasts more English speakers than the United Kingdom), while also bringing his spirited attention to the histories and imaginations of people outside circles of wealth and power. The scales first fell from his eyes during his travels and reporting in Kashmir in the late 1990s and early 2000s. In the disputed Indian-administered territory, he saw firsthand the collision between India’s pluralist liberal democracy—its avowed commitment to democratic norms, individual rights, and multiculturalism—and the reality of military occupation. Indian apologia for abuses in Kashmir, he writes, “prepared me for the spectacle of a liberal intelligentsia cheerleading the war for ‘human rights’ in Iraq, with the kind of humanitarian rhetoric about freedom, democracy and progress that was originally heard from European imperialists in the nineteenth century.” The remit of Mishra’s work has grown steadily wider over the decades, from an early focus on the dreams and catastrophes of small-town India, to a thoughtful exploration of colonial-era Asian intellectual history in the excellent  I wouldn’t wish being Iranian on my worst enemy,” my friend Marjan posted on Instagram in mid-January.

I wouldn’t wish being Iranian on my worst enemy,” my friend Marjan posted on Instagram in mid-January. Black Americans have played a crucial role in helping to advance America’s business, political and cultural landscape into what it is today. And

Black Americans have played a crucial role in helping to advance America’s business, political and cultural landscape into what it is today. And  It is in the middle of winter that the “Arab Spring” comes unexpectedly. On December 17, 2010, in Sidi Bouzid, an agricultural village in central Tunisia, Mohamed Bouazizi, a young unemployed peddler, sets himself on fire after his merchandise is confiscated by police officers. The day after the tragedy, the anger spreads to other cities in the country. President Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, who has been in power for twenty-three years, denounces “terrorist acts” perpetrated by “hooded thugs.” The deaths will soon be counted by the dozens during clashes with the forces of law and order. “Irhal!” (“leave”) becomes the revolution’s byword. Ben Ali is accused not only of having established a police regime, but also of pillaging Tunisia. On January 14, 2011, overwhelmed by the events, he flees with his family to Saudi Arabia.

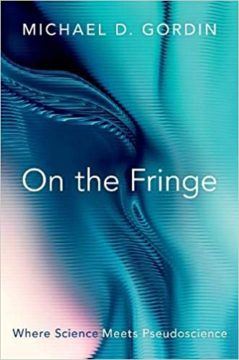

It is in the middle of winter that the “Arab Spring” comes unexpectedly. On December 17, 2010, in Sidi Bouzid, an agricultural village in central Tunisia, Mohamed Bouazizi, a young unemployed peddler, sets himself on fire after his merchandise is confiscated by police officers. The day after the tragedy, the anger spreads to other cities in the country. President Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, who has been in power for twenty-three years, denounces “terrorist acts” perpetrated by “hooded thugs.” The deaths will soon be counted by the dozens during clashes with the forces of law and order. “Irhal!” (“leave”) becomes the revolution’s byword. Ben Ali is accused not only of having established a police regime, but also of pillaging Tunisia. On January 14, 2011, overwhelmed by the events, he flees with his family to Saudi Arabia. It is possible that John Pringle’s neighbors viewed him with some distaste. Formerly physician-general to the British forces in the Low Countries, in 1749 Pringle had settled down in a rather swanky part of London, where he began investigating the processes behind putrefaction. He would place pieces of beef in a lamp furnace, sometimes combining them with another substance — and then wait for putrefaction to commence, or not. Falsifying an earlier hypothesis, Pringle showed that not only acids but alkalis, like baker’s ammonia, could retard the progress of decay. Even more impressively, some substances, like Peruvian bark (source of the malarial prophylactic, quinine) could outright reverse putrefaction, rendering tainted meat seemingly edible again.

It is possible that John Pringle’s neighbors viewed him with some distaste. Formerly physician-general to the British forces in the Low Countries, in 1749 Pringle had settled down in a rather swanky part of London, where he began investigating the processes behind putrefaction. He would place pieces of beef in a lamp furnace, sometimes combining them with another substance — and then wait for putrefaction to commence, or not. Falsifying an earlier hypothesis, Pringle showed that not only acids but alkalis, like baker’s ammonia, could retard the progress of decay. Even more impressively, some substances, like Peruvian bark (source of the malarial prophylactic, quinine) could outright reverse putrefaction, rendering tainted meat seemingly edible again. We live in an era of intersecting crises—some new, some old but newly visible. At the time of writing, the COVID-19 pandemic has already caused nearly 500,000 deaths in the United States alone, with many more deaths on the horizon in the coming months. Since its arrival in the United States, the virus has intersected with and magnified long-neglected problems—radical disparities in access to healthcare and the fulfillment of basic needs that disproportionately impact communities of color and working-class Americans, alongside a crisis of care for the young, elderly, and sick that stretches families and communities to the breaking point.

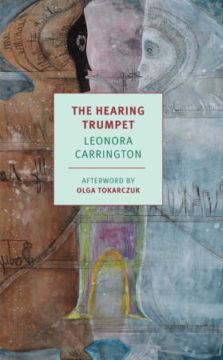

We live in an era of intersecting crises—some new, some old but newly visible. At the time of writing, the COVID-19 pandemic has already caused nearly 500,000 deaths in the United States alone, with many more deaths on the horizon in the coming months. Since its arrival in the United States, the virus has intersected with and magnified long-neglected problems—radical disparities in access to healthcare and the fulfillment of basic needs that disproportionately impact communities of color and working-class Americans, alongside a crisis of care for the young, elderly, and sick that stretches families and communities to the breaking point. “People under seventy and over seven are very unreliable if they are not cats,” somebody says a few pages into Leonora Carrington’s 1974 novel The Hearing Trumpet. Most people would agree; if anything, the bad run of septuagenarians of late shows this age range is too narrow. The statement is characteristic of this chatoyant novel. Cats are everywhere in The Hearing Trumpet: their sheddings are collected to form a sleeveless cardigan; psychic powers are attributed to them; the earth freezes over and an earthquake thins out the human population, but the cats survive. Beneath its cattiness, the remark also offhandedly conflates species (the way “people” transmutes into “cats” at the end of the sentence) and recognizes the virtue of people usually excluded from civic life for being too young or too old. This broadening out of our ordinary categories of human life is at the heart of the novel.

“People under seventy and over seven are very unreliable if they are not cats,” somebody says a few pages into Leonora Carrington’s 1974 novel The Hearing Trumpet. Most people would agree; if anything, the bad run of septuagenarians of late shows this age range is too narrow. The statement is characteristic of this chatoyant novel. Cats are everywhere in The Hearing Trumpet: their sheddings are collected to form a sleeveless cardigan; psychic powers are attributed to them; the earth freezes over and an earthquake thins out the human population, but the cats survive. Beneath its cattiness, the remark also offhandedly conflates species (the way “people” transmutes into “cats” at the end of the sentence) and recognizes the virtue of people usually excluded from civic life for being too young or too old. This broadening out of our ordinary categories of human life is at the heart of the novel.

Klara and the Sun asks readers to love a robot and, the funny thing is, we do. This is a novel not just about a machine but narrated by a machine, though the word is not used about her until late in the book when it is wielded by a stranger as an insult. People distrust and then start to like her: “Are you alright, Klara?” Apart from the occasional lapse into bullying or indifference, humans are solicitous of Klara’s feelings – if that is what they are. Klara is built to observe and understand humans, and these actions are so close to empathy they may amount to the same thing. “I believe I have many feelings,” she says. “The more I observe the more feelings become available to me.” Klara is an AF, or artificial friend, who is bought as a companion for 14-year-old Josie, a girl suffering from a mysterious, perhaps terminal illness. Klara is loyal and tactful, she is able to absorb difficulty and return care. Her role, as she describes it, is to prevent loneliness and to serve.

Klara and the Sun asks readers to love a robot and, the funny thing is, we do. This is a novel not just about a machine but narrated by a machine, though the word is not used about her until late in the book when it is wielded by a stranger as an insult. People distrust and then start to like her: “Are you alright, Klara?” Apart from the occasional lapse into bullying or indifference, humans are solicitous of Klara’s feelings – if that is what they are. Klara is built to observe and understand humans, and these actions are so close to empathy they may amount to the same thing. “I believe I have many feelings,” she says. “The more I observe the more feelings become available to me.” Klara is an AF, or artificial friend, who is bought as a companion for 14-year-old Josie, a girl suffering from a mysterious, perhaps terminal illness. Klara is loyal and tactful, she is able to absorb difficulty and return care. Her role, as she describes it, is to prevent loneliness and to serve.