Rebecca Stropoli in Chicago Booth Review:

Rebecca Stropoli in Chicago Booth Review:

In the early days of the coronavirus pandemic, Hollywood mogul David Geffen enraged many social media users when he posted a photo of his yacht, Rising Sun, on calm waters. “Isolated in the Grenadines avoiding the virus,” Geffen wrote on Instagram. “I’m hoping everybody is staying safe.”

The photo of billionaire life aboard a 454 ft., $590 million yacht inspired plenty of outrage, and even a parody song by singer John Mayer titled “Drone Shot of My Yacht.” As an example of conspicuous consumption, the post highlighted stark global inequalities in wealth and opportunity, and didn’t land well with the millions of people stuck at home in lockdown or risking their health and lives performing essential work.

But when it comes to wealth inequality, a billionaire’s yacht is a sideshow, says Chicago Booth’s Amir Sufi. After all, a yacht is rooted in the real economy. A good chunk of the money originally spent on the yacht went to pay workers and buy equipment, and had a multiplier effect as it circulated in the broader economy. The real problem could be that much of the money owned by billionaires and other wealthy people never makes it that far. “People get angry about seeing the rich consuming a lot,” Sufi says, “but that’s better than what they’re actually doing.”

What’s happening, he says, is that disparities in income and wealth have fueled ever more saving by the top 1 percent. But while many economists think more saving leads to productive investment, Sufi, Princeton’s Atif Mian, and Harvard’s Ludwig Straub make a different argument. They find that these savings are largely unproductive, being remade by the financial system into household and government debt. And their research outlines a cycle whereby the savings of the top 1 percent fuel the debt and dissavings of the lower 90 percent, which in turn leads to more savings at the top.

More here.

This biography’s value and novelty are level-headedness and fine-grained research. Clayton explains rather than exculpates, narrates rather than judges. She sets Hepworth talking through the pages, quoting generously from letters that correct, or complicate, previous accounts of her humourless self-absorption. A passionate and stylish correspondent, Hepworth makes strings of her words: “one’s mind is so turned towards France & the weather & winds & sea!”; “the feel of the earth as one walks on it, the resistance, the flow the weathering the outcrops the growth structure, ice-age, flood”. Clayton uses letters to show again and again how Hepworth doted on her children. On parting with the triplets: “it’s the hardest thing I’ve ever had to think about. I am so deeply happy about the babies & want them with me all the time”. This confirms what Hepworth’s work had already made clear: motherhood and family nourished and inspired her. Many of her sculptures of babies are exquisitely tender, the infant’s skull properly outsized and somehow translucent, as if veins pulsed beneath wooden skin and marble bone.

This biography’s value and novelty are level-headedness and fine-grained research. Clayton explains rather than exculpates, narrates rather than judges. She sets Hepworth talking through the pages, quoting generously from letters that correct, or complicate, previous accounts of her humourless self-absorption. A passionate and stylish correspondent, Hepworth makes strings of her words: “one’s mind is so turned towards France & the weather & winds & sea!”; “the feel of the earth as one walks on it, the resistance, the flow the weathering the outcrops the growth structure, ice-age, flood”. Clayton uses letters to show again and again how Hepworth doted on her children. On parting with the triplets: “it’s the hardest thing I’ve ever had to think about. I am so deeply happy about the babies & want them with me all the time”. This confirms what Hepworth’s work had already made clear: motherhood and family nourished and inspired her. Many of her sculptures of babies are exquisitely tender, the infant’s skull properly outsized and somehow translucent, as if veins pulsed beneath wooden skin and marble bone. It all goes back, strangely, to a trip the French thinker

It all goes back, strangely, to a trip the French thinker  “There is nothing I could write in this book or tell you that would help you get to know me,” writes

“There is nothing I could write in this book or tell you that would help you get to know me,” writes  “YOU ARE GRADUATING AT AN INFLECTION POINT

“YOU ARE GRADUATING AT AN INFLECTION POINT In “The Second: Race and Guns in a Fatally Unequal America,” the historian Carol Anderson argues that the Second Amendment to the United States Constitution, which provides for a “well regulated militia” and “the right of the people to keep and bear arms,” offers “a particularly maddening set of double standards where race is concerned.” On the one hand, she claims that slaveholding founding fathers insisted on the inclusion of the Second Amendment in the Bill of Rights in order to assure themselves of a fighting force willing to suppress slave insurrections. On the other hand, she maintains that racist practices have deprived Blacks of access to arms that might have enabled them to defend themselves in the absence of equal protection of law.

In “The Second: Race and Guns in a Fatally Unequal America,” the historian Carol Anderson argues that the Second Amendment to the United States Constitution, which provides for a “well regulated militia” and “the right of the people to keep and bear arms,” offers “a particularly maddening set of double standards where race is concerned.” On the one hand, she claims that slaveholding founding fathers insisted on the inclusion of the Second Amendment in the Bill of Rights in order to assure themselves of a fighting force willing to suppress slave insurrections. On the other hand, she maintains that racist practices have deprived Blacks of access to arms that might have enabled them to defend themselves in the absence of equal protection of law. Aftab’s new album

Aftab’s new album  I WAS 24 years old when I met Natalia Ginzburg in Rome. I had just come from three weeks of intensive study of Italian at the Universita per Stranieri di Perugia (University for Foreigners in Perugia), and before that had managed to pass an Italian reading comprehension test for a graduate program that I never completed. With the misplaced confidence of the young, I assumed I’d be able to conduct an adequate conversation with her. During the Italian course at Perugia, the teacher had introduced us to Ginzburg’s early essays collected in Le piccole virtù (The Little Virtues) and I was immediately enamored of them. Every lucid, plangent sentence enchanted my ears and twisted my heart. The essay “Broken Shoes” considered the condition of her shoes as she walked through Rome after the fascists murdered her husband, preceded by a spell of political exile with their children in a village in the Abruzzi region. The essays about their life in that town sketched the mutually generous friendships that developed between her family and the local people.

I WAS 24 years old when I met Natalia Ginzburg in Rome. I had just come from three weeks of intensive study of Italian at the Universita per Stranieri di Perugia (University for Foreigners in Perugia), and before that had managed to pass an Italian reading comprehension test for a graduate program that I never completed. With the misplaced confidence of the young, I assumed I’d be able to conduct an adequate conversation with her. During the Italian course at Perugia, the teacher had introduced us to Ginzburg’s early essays collected in Le piccole virtù (The Little Virtues) and I was immediately enamored of them. Every lucid, plangent sentence enchanted my ears and twisted my heart. The essay “Broken Shoes” considered the condition of her shoes as she walked through Rome after the fascists murdered her husband, preceded by a spell of political exile with their children in a village in the Abruzzi region. The essays about their life in that town sketched the mutually generous friendships that developed between her family and the local people. There are many ways to understand the tendency roiling liberal-democratic politics in recent years, from the outcome of the Brexit vote and the presidency of Donald Trump to the surge in support for antiliberal politicians and parties across Europe, Asia, and the Americas. It’s been variously described as an explosion of right-wing populism, a resurgence of nationalism, a renewed flowering of xenophobia and racism, even a rebirth of fascism. But what all of these theories are striving to explain is a pervasive collapse of faith in multiculturalism as an organizing principle of free societies.

There are many ways to understand the tendency roiling liberal-democratic politics in recent years, from the outcome of the Brexit vote and the presidency of Donald Trump to the surge in support for antiliberal politicians and parties across Europe, Asia, and the Americas. It’s been variously described as an explosion of right-wing populism, a resurgence of nationalism, a renewed flowering of xenophobia and racism, even a rebirth of fascism. But what all of these theories are striving to explain is a pervasive collapse of faith in multiculturalism as an organizing principle of free societies. Kink, a new anthology of short fiction edited by R. O. Kwon and Garth Greenwell, intends to “[c]lose some of the distances between our solitudes” by collecting kinky sex-centered stories written by 15 authors of different races, sexual orientations, gender identities, and ethnicities. A quick look at the writers’ bios, though, shows how remarkably alike they are. Five of them graduated from, or currently teach at, the University of Iowa’s MFA program. Almost all are famous in the world of contemporary literary fiction — in addition to the editors, Kink’s contributors include Roxane Gay, Chris Kraus, Carmen Maria Machado, Alexander Chee, and Brandon Taylor. The kink, too, is pretty one-note. There’s a lot of BDSM, most of it light: boot-licking, choking, spitting, and slapping.

Kink, a new anthology of short fiction edited by R. O. Kwon and Garth Greenwell, intends to “[c]lose some of the distances between our solitudes” by collecting kinky sex-centered stories written by 15 authors of different races, sexual orientations, gender identities, and ethnicities. A quick look at the writers’ bios, though, shows how remarkably alike they are. Five of them graduated from, or currently teach at, the University of Iowa’s MFA program. Almost all are famous in the world of contemporary literary fiction — in addition to the editors, Kink’s contributors include Roxane Gay, Chris Kraus, Carmen Maria Machado, Alexander Chee, and Brandon Taylor. The kink, too, is pretty one-note. There’s a lot of BDSM, most of it light: boot-licking, choking, spitting, and slapping.

Who wrote the Declaration of Independence? Thomas Jefferson is generally credited as its author, but Akhil Reed Amar believes there’s a better answer. “America did,” Amar argues in “The Words That Made Us: America’s Constitutional Conversation, 1760-1840.”

Who wrote the Declaration of Independence? Thomas Jefferson is generally credited as its author, but Akhil Reed Amar believes there’s a better answer. “America did,” Amar argues in “The Words That Made Us: America’s Constitutional Conversation, 1760-1840.” The chorus of the theme song for the movie Fame, performed by actress Irene Cara, includes the line “I’m gonna live forever.” Cara was, of course, singing about the posthumous longevity that fame can confer. But a literal expression of this hubris resonates in some corners of the world—especially in the technology industry. In Silicon Valley, immortality is sometimes elevated to the status of a corporeal goal. Plenty of big names in big tech have sunk funding into ventures to

The chorus of the theme song for the movie Fame, performed by actress Irene Cara, includes the line “I’m gonna live forever.” Cara was, of course, singing about the posthumous longevity that fame can confer. But a literal expression of this hubris resonates in some corners of the world—especially in the technology industry. In Silicon Valley, immortality is sometimes elevated to the status of a corporeal goal. Plenty of big names in big tech have sunk funding into ventures to

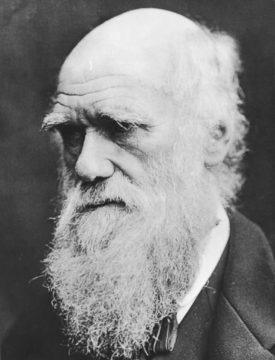

Last week the prestigious and normally staid journal Science kicked up a fuss by running a short essay on Charles Darwin that provoked the anti-woke.

Last week the prestigious and normally staid journal Science kicked up a fuss by running a short essay on Charles Darwin that provoked the anti-woke. President

President