Joshua Hren in The Hedgehog Review:

“Beauty,” David Hume held, “is no quality in things themselves: It exists merely in the mind which contemplates them; and each mind perceives a different beauty.” If this were the case, then the human race’s radical disagreements over aesthetical evaluations would be reducible to harmless preferences. Inclined as we might be to enthusiastically espouse our favorite music as “beautiful,” honesty would require that we chasten our speech, opting for the more modest “beautiful for me,” or—better yet—“I like it,” and nothing more.

“Beauty,” David Hume held, “is no quality in things themselves: It exists merely in the mind which contemplates them; and each mind perceives a different beauty.” If this were the case, then the human race’s radical disagreements over aesthetical evaluations would be reducible to harmless preferences. Inclined as we might be to enthusiastically espouse our favorite music as “beautiful,” honesty would require that we chasten our speech, opting for the more modest “beautiful for me,” or—better yet—“I like it,” and nothing more.

Not a few foes of moral relativism hold to a wholesale aesthetical tolerance, a permissive disposition toward what is called “beauty.” According to this breakdown, we ought to be morally outraged by fraudulence but can in good conscience soak up artless, sentimental movies stamped with “family values”—as if the ugly, caricatured portrayal of things so overwhelmingly good were not an insult, not to say a borderline crime. We shall not murder but there are no nots or oughts governing our responses to Michelangelo.

In very different ways, both the novelist Henry James and the philosopher Dietrich von Hildebrand make the case that moral disfigurement can be ugly and that aesthetic misjudgments can correspond to vicious poverty of the moral variety. They rally praise for the beauty of self-transcendence even as they caution all comers who would relegate aesthetics to the trivial pursuit of pleasure.

More here.

Our ability to experience pleasure, as in the fundamental sensation of something being enjoyable or ‘nice’, is a product of what’s known as the ‘reward pathway’, a small but crucial

Our ability to experience pleasure, as in the fundamental sensation of something being enjoyable or ‘nice’, is a product of what’s known as the ‘reward pathway’, a small but crucial

As the origins of our current moral panic about “white supremacy” become more widely debated, we have an obvious problem: how to define the term “Critical Race Theory.” This was never going to be easy, since so much of the academic discourse behind the term is deliberately impenetrable, as it tries to disrupt and dismantle the Western concept of discourse itself. The sheer volume of jargon words, and their mutual relationships, along with the usual internal bitter controversies, all serve to sow confusion.

As the origins of our current moral panic about “white supremacy” become more widely debated, we have an obvious problem: how to define the term “Critical Race Theory.” This was never going to be easy, since so much of the academic discourse behind the term is deliberately impenetrable, as it tries to disrupt and dismantle the Western concept of discourse itself. The sheer volume of jargon words, and their mutual relationships, along with the usual internal bitter controversies, all serve to sow confusion. In many of our contemporary cultures, the realities of death feel unapproachable. Traditional grieving methods are routinely relegated to the margins, replaced by the medical promise of comforting objectivity. But for those of us confronted by the ebb and flow of complex emotions in the wake of death, the assurance of objectivity falls short. For Ioanna Sakellaraki, this evolving emotional storm, experienced head-on in the wake of her father’s death, is what prompted her to pursue a project on bereavement, finding ways to document the organic chaos that she describes as “the passageway into a liminal space of absence and presence.”

In many of our contemporary cultures, the realities of death feel unapproachable. Traditional grieving methods are routinely relegated to the margins, replaced by the medical promise of comforting objectivity. But for those of us confronted by the ebb and flow of complex emotions in the wake of death, the assurance of objectivity falls short. For Ioanna Sakellaraki, this evolving emotional storm, experienced head-on in the wake of her father’s death, is what prompted her to pursue a project on bereavement, finding ways to document the organic chaos that she describes as “the passageway into a liminal space of absence and presence.” W

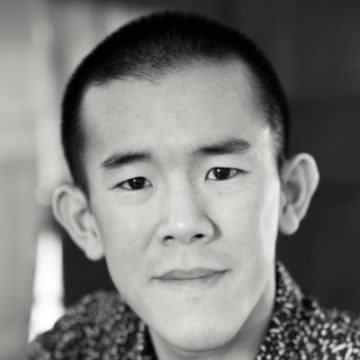

W The Atlantic staff writer Ed Yong has won the 2021 Pulitzer Prize for Explanatory Reporting. He was awarded journalism’s top honor for his defining coverage of the coronavirus pandemic and how America failed in its response to the virus. This is The Atlantic’s first Pulitzer Prize.

The Atlantic staff writer Ed Yong has won the 2021 Pulitzer Prize for Explanatory Reporting. He was awarded journalism’s top honor for his defining coverage of the coronavirus pandemic and how America failed in its response to the virus. This is The Atlantic’s first Pulitzer Prize. When challenged, former President Donald Trump often claimed he was the victim of

When challenged, former President Donald Trump often claimed he was the victim of  Nero, who was enthroned in Rome in 54 A.D., at the age of sixteen, and went on to rule for nearly a decade and a half, developed a reputation for tyranny, murderous cruelty, and decadence that has survived for nearly two thousand years. According to various Roman historians, he commissioned the assassination of Agrippina the Younger—his mother and sometime lover. He sought to poison her, then to have her crushed by a falling ceiling or drowned in a self-sinking boat, before ultimately having her murder disguised as a suicide. Nero was betrothed at eleven and married at fifteen, to his adoptive stepsister, Claudia Octavia, the daughter of the emperor Claudius. At the age of twenty-four, Nero divorced her, banished her, ordered her bound with her wrists slit, and had her suffocated in a steam bath. He received her decapitated head when it was delivered to his court. He also murdered his second wife, the noblewoman Poppaea Sabina, by kicking her in the belly while she was pregnant.

Nero, who was enthroned in Rome in 54 A.D., at the age of sixteen, and went on to rule for nearly a decade and a half, developed a reputation for tyranny, murderous cruelty, and decadence that has survived for nearly two thousand years. According to various Roman historians, he commissioned the assassination of Agrippina the Younger—his mother and sometime lover. He sought to poison her, then to have her crushed by a falling ceiling or drowned in a self-sinking boat, before ultimately having her murder disguised as a suicide. Nero was betrothed at eleven and married at fifteen, to his adoptive stepsister, Claudia Octavia, the daughter of the emperor Claudius. At the age of twenty-four, Nero divorced her, banished her, ordered her bound with her wrists slit, and had her suffocated in a steam bath. He received her decapitated head when it was delivered to his court. He also murdered his second wife, the noblewoman Poppaea Sabina, by kicking her in the belly while she was pregnant. To become prime minister, Mr. Modi overcame a reputation tarnished by his alleged involvement in

To become prime minister, Mr. Modi overcame a reputation tarnished by his alleged involvement in  Mona Ali in Phenomenal World:

Mona Ali in Phenomenal World: Leo Robson in the NLR’s Sidecar:

Leo Robson in the NLR’s Sidecar: