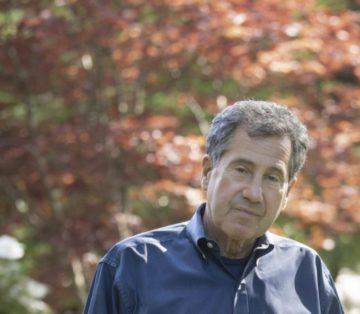

Tarun Timalsina at the Harvard Political Review:

Harvard Political Review: You have called effective altruism, and I quote, one of the great new ideas of the 21st century. Could you briefly introduce our readers to the core philosophy of the effective altruism movement and explain why you think the movement can be a big deal?

Steven Pinker: The idea behind effective altruism is to channel charitable giving and other philanthropic activities to where they will do the most good, where they would lead to the greatest increase in human flourishing. And the reason that it’s needed is that we are all altruistic. It is part of human nature. On the other hand, we have a large set of motives for why we’re altruistic and some of them are ulterior — such as appearing beneficent and generous, or earning friends and cooperation partners. Some of them may result in conspicuous sacrifices that indicate that we are generous and trustworthy people to our peers but don’t necessarily do anyone any good. And so the idea behind effective altruism is to determine where your activities actually save lives, increase health, reduce poverty, and at the very least provide people opportunities to channel their philanthropy where it will do the most good. And, of course, also to encourage people to do that. So part of it is just informing people if that is their goal and telling them that these are the ways to do it. And the other is to spread the value that that’s where philanthropy ought to be directed.

Steven Pinker: The idea behind effective altruism is to channel charitable giving and other philanthropic activities to where they will do the most good, where they would lead to the greatest increase in human flourishing. And the reason that it’s needed is that we are all altruistic. It is part of human nature. On the other hand, we have a large set of motives for why we’re altruistic and some of them are ulterior — such as appearing beneficent and generous, or earning friends and cooperation partners. Some of them may result in conspicuous sacrifices that indicate that we are generous and trustworthy people to our peers but don’t necessarily do anyone any good. And so the idea behind effective altruism is to determine where your activities actually save lives, increase health, reduce poverty, and at the very least provide people opportunities to channel their philanthropy where it will do the most good. And, of course, also to encourage people to do that. So part of it is just informing people if that is their goal and telling them that these are the ways to do it. And the other is to spread the value that that’s where philanthropy ought to be directed.

More here.

ROSENBAUM:

ROSENBAUM:  In the early 90s, governments started buying into an argument about capital mobility, taxes and welfare states: in a world of global capital, investors will seek the best returns they can get globally. If those returns are reduced by “distortions” such as taxes, investment will flow to countries that tax less. Consequently, those expensive and expansive welfare states that neoliberal economists had always targeted had to go. Funding them through taxing the wealthy and corporations would lower investment and employment, so the story went.

In the early 90s, governments started buying into an argument about capital mobility, taxes and welfare states: in a world of global capital, investors will seek the best returns they can get globally. If those returns are reduced by “distortions” such as taxes, investment will flow to countries that tax less. Consequently, those expensive and expansive welfare states that neoliberal economists had always targeted had to go. Funding them through taxing the wealthy and corporations would lower investment and employment, so the story went. Tyree’s answer to our present dilemma is weirdness, “cultivated eccentricity as an antidote to a world gone mad.” He proposes a Pynchonian counterforce, a ragged band of outsiders and misfits to resist all the orthodoxies of the day. Despite the polarization of the moment, both the left and the right feverishly engage in what Tyree terms timewashing: “[O]ur era’s signature creation of fake pasts that purport to cleanse history of its deep stains and recurring nightmares with the scented spray of propaganda.” Our “incapacity to live with the past in all its troubling complexity” poses a grave danger, he argues, and better fiction could be our salvation. He’s right, of course, but he also knows the unlikelihood of his solution: “Is it naïve to assert that we badly need dreamers like Pynchon to help us imagine a different future by reading through a different lens on our past?” Tyree answers his own question just three sentences later: “Yeah, that’s probably naïve.”

Tyree’s answer to our present dilemma is weirdness, “cultivated eccentricity as an antidote to a world gone mad.” He proposes a Pynchonian counterforce, a ragged band of outsiders and misfits to resist all the orthodoxies of the day. Despite the polarization of the moment, both the left and the right feverishly engage in what Tyree terms timewashing: “[O]ur era’s signature creation of fake pasts that purport to cleanse history of its deep stains and recurring nightmares with the scented spray of propaganda.” Our “incapacity to live with the past in all its troubling complexity” poses a grave danger, he argues, and better fiction could be our salvation. He’s right, of course, but he also knows the unlikelihood of his solution: “Is it naïve to assert that we badly need dreamers like Pynchon to help us imagine a different future by reading through a different lens on our past?” Tyree answers his own question just three sentences later: “Yeah, that’s probably naïve.” The Western tradition has never been more appealingly portrayed than in

The Western tradition has never been more appealingly portrayed than in  It’s often cancer’s spread, not the original tumor, that poses the disease’s most deadly risk. “And yet metastasis is one of the most poorly understood aspects of

It’s often cancer’s spread, not the original tumor, that poses the disease’s most deadly risk. “And yet metastasis is one of the most poorly understood aspects of

These squiggles have a meaning. So do spoken words, road signs, mathematical equations and signal flags. Meaning is something with which we’re intimately familiar – so familiar that, for the most part, we barely register or think about it at all. And yet, once we do begin to reflect on meaning, it can quickly begin to seem bizarre and even magical. How can a few marks on a sheet of paper reach out across time to refer to a person long dead? How can a mere sound in the air instantaneously pick out a galaxy light-years away? What gives words these extraordinary powers? The answer, of course, is that we do. But how?

These squiggles have a meaning. So do spoken words, road signs, mathematical equations and signal flags. Meaning is something with which we’re intimately familiar – so familiar that, for the most part, we barely register or think about it at all. And yet, once we do begin to reflect on meaning, it can quickly begin to seem bizarre and even magical. How can a few marks on a sheet of paper reach out across time to refer to a person long dead? How can a mere sound in the air instantaneously pick out a galaxy light-years away? What gives words these extraordinary powers? The answer, of course, is that we do. But how? While the dramatic breach of the Edenville Dam captured national headlines, an Undark investigation has identified 81 other dams in 24 states, that, if they were to fail, could flood a major toxic waste site and potentially spread contaminated material into surrounding communities.

While the dramatic breach of the Edenville Dam captured national headlines, an Undark investigation has identified 81 other dams in 24 states, that, if they were to fail, could flood a major toxic waste site and potentially spread contaminated material into surrounding communities.

A

A If you could soar high in the sky, as red kites often do in search of prey, and look down at the domain of all things known and yet to be known, you would see something very curious: a vast class of things that science has so far almost entirely neglected. These things are central to our understanding of physical reality, both at the everyday level and at the level of the most fundamental phenomena in physics—yet they have traditionally been regarded as impossible to incorporate into fundamental scientific explanations. They are facts not about what is—“the actual”—but about what could or could not be. In order to distinguish them from the actual, they are called counterfactuals.

If you could soar high in the sky, as red kites often do in search of prey, and look down at the domain of all things known and yet to be known, you would see something very curious: a vast class of things that science has so far almost entirely neglected. These things are central to our understanding of physical reality, both at the everyday level and at the level of the most fundamental phenomena in physics—yet they have traditionally been regarded as impossible to incorporate into fundamental scientific explanations. They are facts not about what is—“the actual”—but about what could or could not be. In order to distinguish them from the actual, they are called counterfactuals. The inspiration for

The inspiration for  You observe a phenomenon, and come up with an explanation for it. That’s true for scientists, but also for literally every person. (Why won’t my car start? I bet it’s out of gas.) But there are literally an infinite number of

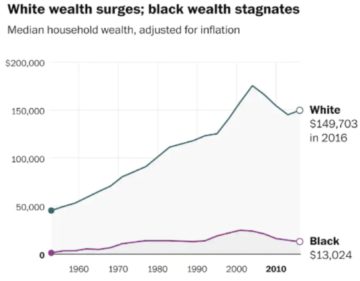

You observe a phenomenon, and come up with an explanation for it. That’s true for scientists, but also for literally every person. (Why won’t my car start? I bet it’s out of gas.) But there are literally an infinite number of  To mark 100 years since the Tulsa Massacre, President Biden

To mark 100 years since the Tulsa Massacre, President Biden